Introduction

According to the most recent Eurobarometer, more than 20% of the European population does not remember a currency other than the euro in their country. Still, many Europeans today question its effectiveness, going back to the 1990s, when the idea of introducing a common currency for the EU was developed. The Great Recession of 2008 and the subsequent crisis of the euro around 2011/2012 resulted in strong criticism of its mechanisms and functioning. Some of them, which we will review later, were entirely unfounded, while other arguments against the euro show strong empirical support. The latter promote a reform movement within the Eurogroup itself. Without denying at all the great virtues of the single currency, they propose a few changes in order to make it more efficient for all countries.

For this reason, this research will not only focus on analysing the effects of the euro on the European economy and, in particular, the Spanish one, but also on proposing, feasible reforms to make it a much more dynamic, competitive and competitive currency that includes all members of the Eurogroup. The euro has provided great benefits, both for Europe and for Spain, but if certain aspects are not modified, its continuity could be questioned by those countries immersed today in the wave of Eurosceptic populism, which is obtaining greater political favour every day in the society of the old continent.

Firstly, the history of the introduction of the euro into the European economy will be briefly described. Afterwards, the main advantages it has brought to Spain will be summarised. Afterwards, its effects on the European economy and, in particular, on our country will be evaluated in depth. Finally, the recent debate regarding the European institutions and their responsibility in the fight against the economic consequences of Covid-19 will be analysed, especially that of the European Central Bank (ECB), and effects of this dispute on the future of the euro and the European Union (EU).

Why did Europe step forward and decide to establish a common currency?

Many Europeans today wonder if the formation in 1992 of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) was an intelligent strategy to face the economic challenges posed to the continent in the 1990s. The answer is yes, both economically and politically, since the opportunities offered in both spheres were considered when introducing a common currency within the single market, although it was established several years before it was effectively circulated. Many criticisms of EMU at the time of its founding focused on the fact that the economic reasons for justifying it were practically nonexistent. They argued, therefore, that it was pure political tactic to deepen the structure of the EU and subtract national sovereignty from the different states of which it was comprised. This exemplifies one of many unfounded arguments that the Eurosceptic groups have been using since 1991 in sovereign movements against the common currency and the European single market.

One only needs to know the Intergovernmental Conference’s decisions prior to the approval of the Maastricht Treaty to see that they were all adapted on a strictly economic basis, adjusted to reality, and far from any type of dogmatism.

The suffering of the economy after the 1973 Oil Crisis must be taken into account in order to place in perspective some of the macroeconomic policy resolutions adopted at the time. After this disruption, the European economies fell into a spiral of high inflation and low growth, which would come to be called stagflation, and which lasted almost a decade in the vast majority of countries. Starting in 1980, the economy of the old continent stabilised again, and growth rates normalised, accompanied by sharp contractions in the inflation rate. This situation largely determined convergent momentum at the socioeconomic level between Europe, USA and Japan after 1980. Thus, it served to reinforce the idea of European integration in the monetary sphere, something already outlined by some of the measures contained in the Werner Report [1] published in 1970.

Later, the debate about monetary integration and the search for greater economic cohesion returned to the political scene in 1985, following the initiative launched by the Delors Commission to gradually introduce a single market in the European Community. One of the EMU’s strengths was to strengthen trade relations between countries and enhance the free market internationally within the Eurozone. Indeed, common currency is not a necessary or private requirement to expand and enhance a free trade area, but it did provide help simplify the legislation dedicated to outlining the new trade conditions, and reduced the factors that economic agents had to take into account when investing or consuming across their national borders.

One of the competitive advantages of the EMU and the Eurozone is that they prevent distortions in trade flows, and dysfunctions in cross-border economic relations due to sudden movements in the value of two or more currencies, which does occur in other areas of international free trade, as we will detail later. This is one of the main reasons why many of the large European industries supported the single market and the common currency, which, in addition, presented a quasi-perfect complementarity. Rightly, many European industry leaders thought that with the EMU they would be able to increase efficiency and productivity. In turn, they would be more competitive in price, both nationally and internationally, by opening up the possibility of extending their supply chains, and see their bargaining power augmented beyond the borders of the continent.

But European employers were not the only ones to give their support to the common currency and single market project. In Germany, the vast majority of unions fervently supported the introduction of the euro, associating it with wage increases, job stability, a revaluation of payments in kind, and an improvement in working conditions. They viewed it as such because the competitive pressure of the labor market would now be extended to the entire EMU, forming an «international labour market,” in which the specialisation factor of some employees would be quoted upwards due to a greater division of labor, which was favoured by the expansion of value chains in the entire continent. In addition, many of the employees of companies that had production and management relocated to Europe would experience less uncertainty regarding the value of their wages due to the elimination of volatility linked to exchange rate fluctuations between the different European currencies, which existed during that epoca. Thus, the common currency has been, is, and will be one of the best structures for protecting workers’ real wages.

The most reliable demonstration of this is the fact that the European Monetary System (EMS) had already served to limit and restrict the fluctuations of European currencies in the late 1980s. It had achieved greater convergence between the main countries of the continent, according to practically all macroeconomic indicators: in prices and costs, it occurred more intensely since the early 1980s sin France and Italy, not to mention in Portugal, Greece and Spain. This strengthened support for the common monetary project, initially comprised of eleven members, and laid the foundations for a stronger and more united Europe.

Another exogenous factor contributing to support was that, although the EMS had decreased the volatility of the exchange rates of European currencies, it had failed to promote the international competitiveness of the vast majority of European nations. Subsequently, trade flows were excessively dependent on the price of the dollar, while many of the cost structures of the main European industries were dependent on the price of Brent oil (in dollars).

We must remember that, at the time, there still existed some strongly restrictive capital controls between European countries, such as those applied by Belgium, France and Italy, and that, after the introduction of the euro, many of them were able to relax, resulting in more lax international capital flows and direct financial investment for business projects in foreign territory. The single market required a unified financial system, whose function converged as much as possible between countries. One of the first steps to be taken was the creation of a common currency, which would guarantee a base of stability in order to eliminate practically all the different limitations to trade between member countries. Furthermore, it could even be argued that it was the removal of some of these restrictions that reinforced the EMU project, whose legislative framework deepened during the meetings held in Hannover, weeks after the cancellation of a large number of capital controls and restrictions on trade with member countries by nations such as Germany. One of the most important decisions agreed in Hannover in 1988 was to design a phased plan for the construction of the EMU and the implementation of the common currency in the markets. Much of the credit for the commercial unification of Europe, and the first steps towards the introduction of the euro, must undoubtedly go to Jacques Delors, who always established himself as a faithful defender of the common European project in the economic sphere.

Therefore, we can verify how the complementarity of a common currency with the functioning of the single market, and the previous base built by the SME, would help to reduce many European economies’ vulnerability to exogenous monetary fluctuations, such as those that occurred during the stagflationary period. The best solution, therefore, to guarantee the free movement of goods and capital across the continent within a stable framework that promoted economic convergence among the European nations consisted, not only in the establishment of a single market, but in that of a single currency which would guarantee greater commercial and financial dynamism in the European environment.

Counterfactual exercises which play out the commercial and financial scenario if the euro had not finally been implemented present very valid and relevant arguments when investigating the effects of the single currency. The main problem is that the conclusions of these counterfactual studies are disparate to the point of being incompatible. Therefore, the scenarios presented by economists such as Joseph Stiglitz [2], Yanis Varoufakis [3] or Phlipp Bagus [4] (each from their different perspective, partly ideological) would have to be analysed individually, an objective that is beyond the reach of a research article such as this, mainly for a matter extensiveness.

The political issue around the euro

Many analysts, economists and political scientists have stated on numerous occasions that the euro, in spite of technical or economic reasons, ended up being introduced, and its implementation accelerated, due to a purely ideological issue, intending to seal the structure around the common European project and raise a barrier against its demolition. This discourse began to spread, especially among the French Eurosceptics. They blamed Germany for pushing for the approval of EMU and rising as the leading voice of Europe, both politically and economically, being able to directly confront global economic giants like EE USA or China. This message spread throughout the years, until it formed strong eurosceptic (and anti-euro) movements such as the Northern League in Italy, Syriza in Greece, and Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland [5].

These movements frontally break with the conservative parties and politicians of the 20th century, who, although not entirely favourable toward the project of European unification, and in many cases, contrary to its enlargement, never tried to obstruct it or push it back. Examples of such conservatives are Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher, far removed from the arguments of the current Eurosceptic currents.

It is absolutely implausible, as many have alleged, that the demolition of the Berlin Wall acted as an enzyme for the construction and implementation of the EMU, since the plans and main political and economic provisions had been previously outlined, as we have seen. Not only did the meeting in Hannover of the European Council — headed by Delors — in 1988 serve to firmly lay the foundations of EMU, but in addition, these proposals were ratified and expanded at the European Council meeting held in Madrid in June 1989, almost five months before the Wall’s collapse. Likewise, German reunification greatly destabilised Bavarian public finances and made them less competitive at the international level, mainly due to the high level of deficit that emerged in the German public accounts after the process. It should be recalled that the positions of Germany’s macroeconomic policy in the 1990s were not at all similar to those maintained today by its government and public institutions. For example, from 1989 to the years 2003-2004, they advocated a much looser and more accommodative monetary policy than what they subsequently demanded, in part to compensate for the fiscal policy restrictions they had to apply at the time, and in order to reduce the deficit bequeathed by the communist regime.

Therefore, the adoption of the common currency had a solid economic base, formed mainly by the desire of the member countries to reduce the volatility of their countries’ exchange rates and achieve greater economic convergence. Perhaps, the fact that the common currency was established solely on the basis of economic arguments — leaving political considerations aside — may have been one of the main causes of some failures presented by EMU, which we will list at the end of this investigation.

Who drove the adoption of the euro?

Long before the euro was enforced, and even before the EMU, the two countries par excellence that called for the need to articulate a common currency were France, Italy or Germany, with the unconditional support of Delors and the European Commission. The EMS had guaranteed prosperity to a large number of small countries on the continent, who had witnessed their incomes converge, to a greater or lesser extent, towards those of leading nations such as Germany. For this reason, they saw in the single currency an opportunity to finish eliminating the latest trade frictions and economic asymmetries with the great European powers.

On the other hand, as previously mentioned, France or Germany offered strong support for the European common currency project, as well as for the establishment of the EMU. Still, their motives for doing so differed greatly from those of the more «peripheral» nations of the old continent.

Germany, always concerned about budgetary stability and contained inflation, strongly supported the introduction of the euro because it believed (quite rightly) that it would bring macroeconomic stability, generate a contraction in volatility, and allow for moderate and lasting inflation levels. In this sense, the Bundesbank has always prioritised monetary policy measures aimed at suppressing inflation outbreaks, together with macro-prudential government policies to guarantee budget stability and economic growth. For all these reasons, the Bundesbank was listed as one of the main signatories to the 1989 Delors Report.

France, for its part, wanted to share Europe’s economic leadership with Germany, at a time (1980s and 1990s) when both powers were much more evenly matched, both economically and geo-politically. Therefore, this greater balance of power was France’s incentive to present itself as the spearhead of the European economy, and to fully support the EMU and euro projects.

Accepting the ECB as an institution independent of the different national governments in charge of monetary policy was a great challenge for many countries, especially the least accustomed, such as France, whose central bank did not obtain full independence from the Executive until 1993, just a few years before the formation of the ECB. The French, in addition, understood the euro as one more tool to end asymmetric shocks and be able to compete on a commercial level in a much more stable way with Italy, Germany or Spain.

Meanwhile, the Germans, although enthusiastic about the common European project and promoters of political cohesion, wanted to maintain certain sovereignties that, in some aspects, they believed would be potentially harmful if they were ultimately unified. One of them was, and is to this day, fiscal policy. Germany, along with many other members of the EU, has strongly opposed a fiscal union and introducing certain structural policies from Brussels, mainly due to the economic dysfunctions that this could cause, as there is great heterogeneity in the productive structures of the different countries of the EU.

The acceptance of the common currency and the rejection of the fiscal union by Germany were not only not contradictory, but ended up being complementary. This is because subtracting sovereignty from the participating nations of the EMU implies restricting the availability of resources that different governments can use in their economic policy. Therefore, the fiscal independence of the members of the EMU was more essential than ever — not only to provide a certain sovereignty to the countries, but also to guarantee competition between them after the introduction of the euro. After entering the EMU, and thanks to the macroeconomic stability provided by the common currency, the States could compete in terms of quality, added value and attraction of foreign capital, through the adaptation of fiscal policy to their needs and movements. As we will see later, when we turn to the available empirical evidence, the euro helped to reduce the diversion of risk premium between Member States, ensured greater security for lenders and borrowers, kept consumer prices stable, and prevented further ills at difficult times such as the Great Recession of 2008 or the euro crisis of 2011/2012.

The discipline of the Maastricht Treaty

One safeguard of the European economy and its stability at the macro level, at least in budgetary and fiscal terms, has rested through the years on the Maastricht Treaty. In it was an agreement that member countries would be subject to a series of limitations, especially in the deficit-debt binomial, in order to guarantee a healthy basis for economic growth — sustained over time — and at the same time, try to avoid public debt bubbles or growth rates fed by deficit excesses. To do this, the Excessive Deficit Procedure (PDE) was established, along with the Stability and Growth Pact, with some stipulations such as a fiscal deficit limit of 3% of annual GDP, prior to entry into the PDE, and a level of public debt equal to or less than 60% of GDP — a figure that, since 2008, a large number of European countries have been defaulting on.

The Maastricht Treaty focuses primarily on fiscal policy issues; for example, leaving aside deficits in the balance of payments, or the deficit and debt of private entities. These policies of budgetary stability have guaranteed greater capital mobility, and consequently, greater flows of direct financial investment throughout the EMU.

The main initial role of the ECB was to keep inflation stable and relatively low, and to protect the European economy from external pressures and from the dysfunctions that could generate, especially those stemming from financial markets. We must not forget that, in the field of regulation and supervision, the ECB has a very minor role, although it should be noted that it comprises the Single Supervisory Mechanism, along with the regulatory authorities of the member countries. Others, such as the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), established in 2012, in the midst of the euro crisis, have shown great effectiveness in ensuring financial and macroeconomic stability in the EU to the extent their powers permit.

At all times there have been strong arguments, both political and economic, to make an effective and compelling defense of the euro. After its introduction there was an excess of optimism, and many argue that all the expectations placed on it have not yet been met. However, this is not enough to try to destroy it and return to the monetary trenches. Without a doubt, aspects of its operation must be corrected and improved, but clearly, the euro has been an economic blessing for Europe, and therefore for Spain.

How the euro has benefited Spain

Our country was one of the pioneers in the implementation of the European common currency, now over 20 years ago. This decision shelved any hint of an autarkic, protectionist or isolationist policy that could still remain from past decades. Therefore, it was not only a boost for Spain at an economic level, but also a political one, by internationalising and opening up both our economy and our diplomatic relations.

One of the points that all opponents of the common European currency highlighted at the time was that it would eliminate Spain’s power, at the state level, to manipulate interest rates and the volume of money supply, and therefore the value of the currency, which would supposedly detract from economic policy tools, especially in relation to international trade. The ECB would later be in charge of controlling these aspects in the Eurozone economy, without the member countries having individual sovereignty to interfere in such decisions. This would forge a true independence of the central bank with respect to the States.

This inability of the central government to devalue the currency or arbitrarily reduce interest rates was criticised by many after the start of the Great Recession, beginning in 2008. They argued that Spain was in a spiral of losing competitiveness on an international scale due to the impossibility of depreciating the currency and «protecting» itself from the adverse macroeconomic conditions that it experienced. Unable to resort to this devaluation, in to maintain the competitiveness of our economy, the different governments from 2008 to practically 2014 had to introduce structural changes that guaranteed greater and faster job creation (especially with the labor reform of 2012), moderate the fixed costs of the economy (including salary income), and allow a rapid adaptation of the Spanish business fabric to unfavourable conditions. Said structural adjustments, with greater or lesser success, managed to stimulate job creation, economic growth, and even equalise and exceed the volume of aggregate wage income in 2007. That is, thanks to the impediment of arbitrary devaluation for being members of In the eurozone, the Spanish government was «forced» to face far-reaching structural reforms that it would never have carried out if it had had other macroeconomic policy tools. It was, therefore, tremendously positive.

Under the leadership of José María Aznar, whose mandate began in 1996, Spain made the decision to join the EMU which would take effect three years later. But our country, in 1996, did not even remotely meet the necessary requirements to become part of the EMU in terms of deficit, inflation, interest rates or public debt on GDP. These limits were governed under the regulations established in 1992 through the approval of the Maastricht Treaty, as previously commented.

In 1995, the public deficit of the Spanish State was at 6.79%, and had to be reduced to 3% of the GDP established by the Maastricht Treaty, while the public debt stood at 61.4% of the GDP in 1995, and 65.4% in 1996. For its part, inflation amounted to a high 4.5% in 1995. Because of all this, the Spanish government launched a series of policies aimed at reducing public spending, promoting some privatisations, and introducing some structural measures (with a view, some of them, to lessen the impact of automatic stabilisers on the public deficit). The results of these policies were a complete success, since the public deficit rose to 1.24% in 1999. By that year, public debt had dropped below 60% of GDP, and inflation was contained at 2.31%.

These structural reforms allowed for sustained and relatively high economic development throughout those years, with growth rates ranging from 3% to 5.5% year-to-year. As William Chislett, associate analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute, points out in a paper published in 2019 [6], per capita income in Spain increased from 80% of the average of the 15 EU member countries in 1996 to the 87% in 2004, largely thanks to the creation of 1.8 million new jobs in the period described, which lowered the unemployment rate from 23% to 11.5%. We must also not downplay the fact that this economic growth, especially once the new millennium began, was largely driven by widespread debt in the private sector, especially in construction, which went from representing close to 7.5% of Spanish GDP in 2000 to almost 11% in 2006, through massive injections of credit that helped inflate a bubble that ended up exploding in 2008.

The interest rate curve declined horizontally in the referenced period, due to a contraction in the yield of sovereign bonds, regardless of their maturity. Again, as Chislett points out in his study [7], the rate of short- and long-term sovereign bonds fell from 13.3% and 11.7% respectively in 1992, to 3% and 2.2 % seven years later, a trend that was reversed to 2.2% and 3.4% in 2005. This favored greater consumption and greater risk-taking by banks, which made the parameters used in their analysis more flexible for credit risk, and they offered, on many occasions, loans without any type of collateral or guarantee. This happened repeatedly with those made by the savings banks; a public pseudobank that, after the 2008 crisis, suffered extremely high delinquency rates and an enormous fragility of balance sheets. Indeed, regulators could have done much more in this regard, and some agencies’ duty of vigilance and warning was not exercised as effectively as possible. Even so, in this scenario, the euro proved to be beneficial to Spain, since it was precisely membership in the Eurozone that allowed the country to be partially rescued by the European Stability Mechanism in 2012. Without this, many structural reforms could not have been carried out due to the serious situation in the Spanish economy.

Many problems, such as the high structural unemployment, the high rate of temporary employment, the small increases in productivity, or the weakness of its productive fabric due to the large proportion of SMEs and micro-SMEs, are in no way symptoms of the euro, but of the lack of openwork reforms that have been absent for so long in Spain. This lack has caused the average unemployment rate of the historical series rise to 17%, and the fact that recently there have been temporary rates of more than 30%, or that more than 99% of our production structure is made up of micro and small businesses [8].

The large contraction in interest rates and the notable decrease in the risk premium were mainly due to the entry into force of the euro. To put the situation in context, after its implementation, the Spanish risk premium (difference in profitability between the Spanish and German bond) decreased from 500 basis points to around 50. A drop of more than 90%. This espoused, to a large extent and together with the commercial unification of the economy, that Spain’s direct financial investment abroad grew from $129,000 million in 2000 to $ 597,000 in 2017. Meanwhile, what which targeted Spain increased, in the same period, from $ 156,000 million to $644,000. This greatly helped the socioeconomic development of the nation.

Furthermore, thanks to the euro and the bargaining power that the EU has in the international market with respect to that held by Spain individually, in those seven years the foreign sector managed to go from constituting 26% of the Spanish economy to more than 33%. A complete commercial and productive diversification success through a long process of internationalisation.

This does not mean that the euro is not defective or that the Spanish economy has not experienced any problems due to it, but rather that there are certain design flaws in the EMU that must be solved by means of an internal reform, which introduces to the debate some elements such as the banking union, or to complete filing some fringes of the Maastricht Treaty, as advocated by different European members. A positive element to introduce would be the reception of certain aid by the EMU countries as a condition of the implementation of certain structural reforms, as if it were a system of conditional cash transfers (CCT).

Next, we will analyse the empirical evidence available on the functioning of the euro, and its effects and future, to further delve into the role of the ECB, monetary policy and its consequences in the medium and long term.

Analysis of empirical evidence

As has been commented throughout the investigation, the introduction of the euro guaranteed less volatility in the exchange rate of the common currency compared to the previous situation. In turn, subsequent injections of liquidity by the ECB the Great Recession of 2007 had less marginal effects on economic instability than the destabilisers that before caused liquidity injections from national central banks. Therefore, this could be considered a clear triumph, not only of the common currency, but of the entire EMU, since one of the main objectives — perhaps the most important for its functionality — was to ensure a stable euro exchange rate against foreign currencies. If we compare the volatility of the currencies of other EU member countries not attached to the euro, this is something that has been successfully achieved.

Likewise, it is necessary to repeat that the benefits of the single currency, such as greater economic stability, less fluctuation in the exchange markets, and even controlled inflation, also entail costs, as analysed by the theory of the Optimal Monetary Areas [9]. This refers to how, in a situation of asymmetric economic shocks, said common currency could harm the worst-off countries, reducing their competitiveness in the international market and generating an impossible additional cost assumption. In this regard, the Great Recession was an example of quasi-symmetrical economic shock in Europe, although it is true that some nations had developed certain macro-prudential policies in the years prior to 2008, while others carried an absolutely deplorable fiscal balance in a boom situation similar to the first years of the twenty-first century in the old continent.

Currently, eight EU countries continue without adopting the euro (discounting the United Kingdom), while in 2007 there were 11. In some of them, especially Hungary, Sweden and Poland, between 2004 and 2009, the volatility of its exchange rates increased enormously in contrast to the relatively lower one experienced by the euro.

If we look at the IMF statistics, the coefficient of variation [10] against the euro in countries such as Hungary or Poland between January 2004 and July 2007 was, respectively, 0.034 and 0.071, while, between July 2007 and March 2009, it shot up to 0.073 and 0.103. As for the percentage change in the exchange rate against the euro in the period from July 2007 to March 2009 (dates indicated by the bubble burst), it was -19.2% for Hungary and -19.6 % for Poland [11].

Along these same lines, we can point out that the aforementioned currencies not only showed enormous exchange rate volatility against the euro, but that they also devalued sharply in short time intervals. This same exercise can be carried out to analyse the volatility of the interest rates of the 10-year sovereign bonds of the different countries, comparing the members of the Eurozone with those of the EU who are not part of the common currency. The data should only be observed until 2009, because after the explosion of the 2008 crisis, monetary policy in all countries — albeit in very different ways — abandoned normality and standard objectives, which resulted in a prolongation of low interest rates (even 0 or negative towards the end of the second decade). This eliminated all traces of stability and generated major dysfunctions in the sovereign bond market, with very short-term (1 or 2 years) yielding negative real rates, and bonds from some countries such as Germany even yielding negative nominal rates.

Therefore, for the study of the volatility of interest rates of sovereign bonds to be relevant at an empirical level, the period to be studied will be the same as in the previous year (2004 to 2009); this study will only evaluate the fluctuation of 10-year sovereign bonds between countries of the two groups already identified and described.

Again, if we use the coefficient of variation with respect to the average interest rate of each bond in the indicated period, we see that the average for the member countries of the Eurozone, between January 2004 and July 2007, is 0.117, and since the beginning of the crisis, that is, from July 2007 to March 2009, it is 0.055. Meanwhile, the average of the coefficient of variation of the EU countries who are not in the Eurozone is estimated, for the first period indicated, at 0.122, and in the second, at 0.124, which shows that not only did the volatility of sovereign debt rates increase for European countries outside the euro, but remained higher at all times. This difference was more pronounced during the start of the Great Recession (between July 2007 and March 2009).

This analysis proves that the members of the Eurozone suffered less volatility in the financial markets — at least in the foreign exchange and sovereign debt markets, which are the two of the most important for the States when it comes to being able to maintain stability in a time of foreign currency reserves and accessing global debt markets in search of financing. The fact that both markets suffered less volatility for the countries participating in the European common currency project provided some macroeconomic stability and a continuous possibility of access to finances through the markets, especially in months as complicated globally as those that marked the first phases of the Great Recession.

This does not mean that some countries, especially in the Mediterranean environment, did not see their risk premium soar, in the case of Greece, Italy or Spain. What we can gather is that this increased less than it probably would have if they had remained outside the Eurozone. Again, it should be noted that this last part is only a deduction drawn from the trends obtained in the analysis made a few paragraphs above. In this context, a counterfactual exercise could be carried out to establish what the behavior of the risk premium would have been for these countries if, at the start of the 2008 crisis, they had not belonged to the Eurozone. However, it would be very complex and unreliable since we do not have information on the reaction of currencies such as the peseta or the Italian lira in situations of economic shock at the magnitude of the Great Recession, in an absolutely internationalised economic environment and with highly developed financial markets.

On the other hand, the stability of interest rates and the low relative volatility of the exchange rate do not constitute an absolute guarantor in preventing asymmetric economic shocks. In other words, the same recession can have very different macroeconomic consequences in two different countries, although both are in the Eurozone. The crisis derived from the US subprime bubble had a greater effect on those nations that had previous structural weaknesses and whose productive and business fabric reflected certain characteristics that acted as aggravating factors. For example, in Spain, the high debt of the real estate sector, and the growth of its weight in relation to the GDP, especially until 2007, reflected an evident structural fragility of the economy, as in Ireland and many areas of France. In addition, the financial sector suffered more in some European countries for different reasons. Spain, for example, suffered due to its own structure and the great weight of savings banks, which proved to be the spearhead of corruption, inefficient management and late payment. By contrast, Belgium and France were was weighed down by the large volume of US mortgage-linked securities in national banks. However, although some Eurozone countries suffered more than others due to their particular economic vulnerabilities, the euro largely avoided an outbreak of volatility levels, as previously discussed.

Some experts, such as Barry Eichengreen in a paper published in 1995 [12] together with Charles Wyplosz and Andrew Rose, show that despite strong economic unions, if a common currency is not introduced in the optimal monetary areas, an asymmetric shock can lead to negative perception spirals. These, in turn, drive strong downward speculative pressures and trigger volatility in exchange rates within the economic area itself. This would also cause a greater variance in risk premiums than if a common currency were available within an optimal monetary area. The example given by Eichengreen to reference his theorising exercise is based on the crisis of the 1993 European Monetary System, and in particular on two currencies belonging to it: the sterling pound and the Italian lira. He evaluated the collateral effects of its high volatility at the time on the rest of the EMS currencies. With the financial markets overvalued according to the analyses of practically all the economists who dealt with the matter, such as the aforementioned trio, the strong pressures on the price of these currencies caused national governments to abandon their respective fixed exchange rate regimes to adjust the price of the two downward, and thus cushion the dysfunctions that were being generated in the exchange markets and their effects on the «real economy.” One of the aspects highlighted by Eichengreen et al. in the 1995 paper is that, from the moment in which both governments abandoned the fixed exchange rate and the prices collapsed, the general narrative in the markets began to offer an image of generalized weakness in the EMS, which caused a widespread downward pull in prices of all the currencies that were framed in it.

Economists who are more skeptical of the euro, such as Martin Feldstein, gave an example of the increases in the risk premium, especially in Ireland and Greece after the start of the Great Recession, as a demonstration of a failure of the EMU, and above all, of the – according to Feldstein – serious errors in the design, implementation and operation of the European common currency. In his analysis, Feldstein [13] argues that economic disruptions with asymmetric effects show the high opportunity cost of giving up monetary sovereignty in favor of the euro, preventing each country from directing its own monetary policy and adapting elements such as rates of interest, the monetary base, or the value of the national currency to the changing macroeconomic. Along the same lines, Feldstein argues that the friction between the members of the Eurozone does not allow an effective joint monetary policy to be carried out, precisely because of the marked structural differences between these countries.

A predictive error that Feldstein made in the 2008 article cited above was to forecast that, due to the increase in spreads between nations such as Greece, Ireland, Spain or Italy with respect to Germany — at the beginning of the Great Recession — strong internal pressures would end up causing the exit of the euro from some of the states supposedly most affected by its structure and operation. This has not yet happened, despite the Eurozone having gone through times like the currency crisis in Greece, which came dangerously and unconsciously to the brink of a return to the drachma.

One detail that has largely overlooked is the fact that, while the risk premium shot up at the beginning of the Great Recession, the growth of the rate differential of the corporate bonds with the highest credit ratings did not increase so abruptly. This shows that the markets relied much more on the solvency of the private entities, while they feared a non-payment of the public debt, due to the excessive accumulation of some countries like Greece and Italy, with current public debt ratios of 178.20% and 137.3% of GDP, respectively (Q3 2019 data) [14].

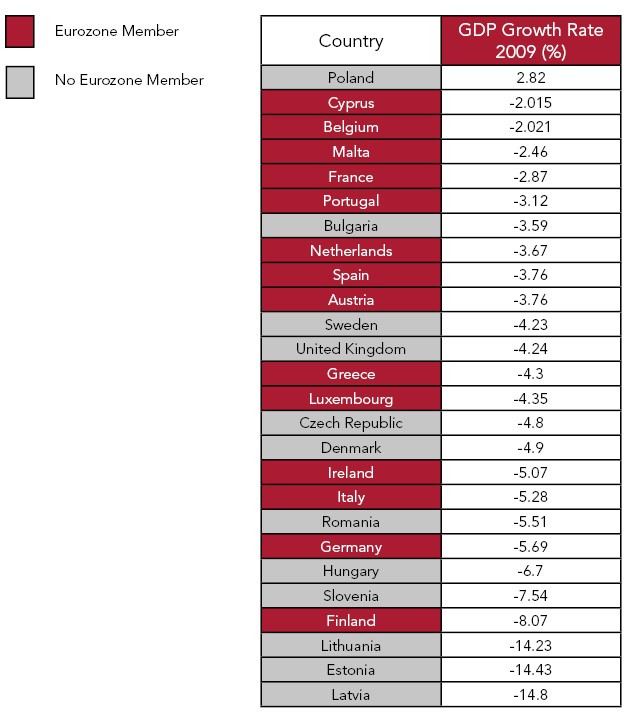

Regardless of these differences, the situation was much worse for EU members not participating in the common currency, both in terms of exchange rate volatility and increased risk premium. Some, in the case of Hungary and Latvia, even saw the need to go to the IMF in search of a liquidity injection. Nor were EU countries saved on the currency board, such as Lithuania and Bulgaria, whose results from various indicators proved much worse than the countries of the Eurozone. Specifically, within the EU, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania registered the greatest falls in real GDP in 2009. In all three cases, these contractions exceeded 10%, as shown in the graph below.

Graph 1.

Some economists have studied the relevance of monetary autonomy in times of economic shocks, such as Kenneth Rogoff et al. [15], who, in a paper published in 2004, tries to reflect that, in times of economic crisis, within an optimal monetary area, in the absence of a common currency — and this being the ideal solution — the worst alternative would be in the national currencies with a fixed exchange rate, since, on the one hand, the advantages of stability and economic cohesion that monetary unions provide would be lost, and, on the other, the flexibility of monetary sovereignty outside a fixed rate regime would also be lost. The above data shows precisely the correlation between worst economic performers recorded in 2009 (in terms of real GDP variation) and those with the highest risk premium, and with the highest volatility in interest rates of sovereign debt and the exchange rate, like the Baltic countries.

One of the main purposes of the euro was to achieve full integration of financial markets and European trade. Much progress has been made in this direction, and progress has been rapid and decisive, but its absolute achievement has not been possible, largely due to the protectionist policies and attitudes adopted by the member countries of the EMU. This protectionism, in turn, has generated greater friction in the European markets, both in the corporate debt and in the various exchanges, not to mention the trade in goods and services typical of the «real economy,” which, even having been facilitated thanks to the functioning and structure of the single market, continues to present unnecessary obstacles and difficulties of an economic union [16]. There is still a long way to go in terms of regulatory unification, homogenization of trading platforms, legislation that is as cohesive and uniform as possible, and common supervision of trade at both European and foreign level. The euro, as a vector that transmits economic and social cohesion, has helped toward significant progress in these fields, but without a real impetus from the Member States to de-bureaucratize and deregulate at national level, in favour of a European commercial unification at the level legislatively, the euro will soon see itself reflected in its own glass ceiling.

We must not be so naive as to think that member countries maintain regulatory and bureaucratic differences for the sake of greater competition and economic freedom. As we have commented, the background of Eurosceptic attitudes and policies is fully protectionist. Many do not want their strategic industries forced to compete in a global market, as would happen to the entities that make up the financial sector if they were not backed by their states. Different national regulations require very specific product qualities to allow for introduction and distribution in the country, and are nothing more than a tool to establish high barriers to entry to foreign competition and make competition difficult (even with the trade facilitation that the EU single market structure entails) in various markets and industries that, due to various captures by the regulator, states prefer to keep protected.

On the other hand, an integration and homogenisation of financial regulation at the European level, which would eliminate bureaucratic spreads between member countries, would help maximize the benefits of the structure of the single market and the common currency. The Great Recession showed how the lack of cohesion and unity at the regulatory level (which does not require more regulation, but less, but more flexible, simplified and common for the Member States) had serious effects on the financial sector, resulting in harmful consequences for European citizenship. It is very optimistic that a bank can operate without added difficulties in several countries and, in turn, belong to international entities, but then, there must be facility (and not cumbersome) regulatory and arbitration mechanisms for when, in a situation of economic shock, said entity suffers high probabilities of bankruptcy, as occurred in the years after 2008. As this affects creditors of several different nationalities, there would have to be an instrument for rapid resolution, so that the effects of the shock are not spread indefinitely by all member countries. The Single Resolution Mechanism, established in 2014, has done and is doing much-needed work since — especially when it comes to ensuring transparency in the financial sector and the transfer of information between national regulators — by minimising costs of the resolution in each country and erasing uncertainty in situations of economic shock such as the Great Recession of 2008.

Transferring sovereignty to the European organizations does not mean a loss of freedom, competitiveness or efficiency, but rather the opposite. The real danger comes when we have banks operating globally and a very high volume of inter-European trade, but continue to maintain hundreds of thousands of specific regulations at the national level in each Member State, thus avoiding real competition in Europe and an authentic search for efficiency through internationalisation of the markets.

Discretionary policies between the different states of the Eurozone, such as the monetary policy of the ECB, may have been and will be one of the major destabilising factors of the common project, when confronting strong interests of the countries of Central Europe versus those of the South. The asymmetric fiscal policy of these two groups over the last five years also constitutes a discrepancy when designing a joint shock policy to try to mitigate the pernicious economic effects that will be unleashed as a result of the crisis of the Covid-19. Proof of this is the debate that emerged in the last weeks of March on the role that the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) should play in the current situation.

European monetary and fiscal policy, antibiotic or palliative care for the European economy?

In recent weeks, discussion has intensified over the need for common European sovereign debt, and the possibility of starting to establish a tax union, in order to have sufficient fiscal and budgetary capacity to face economic shocks such as the current one — which will be more obvious over time. This has generated a strong confrontation between the southern and northern European states, on account of the desire to mutualise the risk of the former, and the refusal of the latter. This alludes to the fiscal and budgetary recklessness of the former, which led them to be without sufficient capacity to face this crisis. Meanwhile, the ECB, after a hesitant and confusing initial response, decided to launch a buyback program (massive QE) worth €750 billion. Are these policies real solutions for the European economy, or just a boost forward that will only serve to postpone or nullify necessary structural reforms? Do they jeopardize the common European project by not taking into account the moral hazard that they introduce and the reactions that this could generate in the countries that are most reluctant to them?

First of all, it is necessary to consider that, if movement towards a fiscal union (something not clearly positive) is truly desired, the current divergences in this matter between Member States should be eliminated, since, otherwise, it would be practically impossible develop a common, strong and competent tax mechanism. It should be emphasised at this point that convergence should not be upward, but rather downward. Currently, the fiscal divergence between some European states (in terms of public spending) reaches high levels of 30.6 points, due to the disproportionate public spending of some nations such as France, if we compare it with Ireland. Thus, the weight of public spending on Irish GDP amounts to 25.4%, while in France it stands at 56%, due to the large differences in national fiscal policies.

Europe must be configured as a political and economic union. Politically, it must defend the unity of action, the cultural and social interrelation between its States, and a common attitude and strategy in regards to the great global powers such as the USA and China. In the economic dimension, it would have to recover the essence of the Europe of the merchants, facilitating international trade, which would impose conditions, even structurally, for fiscal and budgetary policy to its member countries to achieve prolonged stability of public accounts across the EU, something that has not yet been achieved with the Maastricht Treaty, and setting an example for liberalising policies. The EU itself admits that the total cost of its bureaucracy and regulation is around 4% of GDP [17] of the 28 members as a whole (the data also includes the United Kingdom).

Some economists, such as the EsadeEcPol working group, composed of the renowned Antonio Erce, Antonio García Pascual and Toni Roldán [18], extend the proposal of Bénassy-Quéré et al. that the ESM could provide the countries of the Eurozone with financing at their own triple A debt rates, analysing the assumption in depth for the case of Spain.

To carry out the study, the authors use a framework of debt sustainability, trying to demonstrate that a loan from the ESM without margins and with extremely benevolent conditions would help stabilise Spanish public debt at 125% of GDP, starting from current levels, which would include a maximum of gross financing needs of 20% of annual GDP. Along these same lines, they argue that, with current interest rates, the proposed MEDE aid program would bring about 150,000 million savings for Spain in terms of payment of interest accumulated over a period of 10 years (between 2020 and 2030 ), consequently reducing the fiscal effort. In turn, they highlight the need for the ECB to activate an OMT (Outright Monetary Transactions) program to accompany the ESM’s policies. These proposals, even though they are extremely rigorous and viable if the institutions are aligned in their favor, present some implementation difficulties, as well as economic and political side effects.

The ESM has its own resources of 410,000 million euros, so that only the credit destined for Spain, according to the proposal of the aforementioned economists (200,000 million euros) would represent about 49% of the total. Therefore, if a common European policy is to be deployed in this regard, the financial resources of the ESM should be increased, something that must be agreed between the member countries. Even so, in the event that this extension is approved, it is a very long and tedious process, so it would surely end when these resources are no longer strictly necessary. Likewise, it should be noted that the statutes of the ESM themselves require that some type of conditionality be applied to all its lines of credit, which would entail an additional cost not internalised in the analysis was carried out.

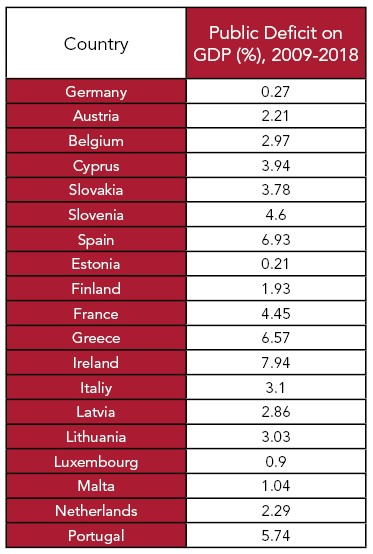

This conditionality, even being flexible and soft, would imply some type of budgetary restriction or obligation of structural reforms. Theoretically, this should not be a problem for Spain, whose Constitution includes fiscal balance in article 135, despite the fact that it has been treated as wet paper in recent years. On more than six occasions, our country has failed to meet the deficit target with Brussels, and this now diminishes credibility when requesting economic support and mutualisation of the risk of sovereign debt to countries that have maintained sound accounts and rigor budget requirements, such as is the case with Germany and the Netherlands. It can be seen in the following graph, where the average public deficit (measured on GDP) of all the Member States of the Eurozone from 2009 to 2018 is shown (latest official data available).

Graph 2.

At this point, we must avoid selling ourselves to the economic populism typical of anti-austerity political movements, and stress that a balanced budget does not include as a sine qua non condition cuts in essential services, such as health or education. Moreover, in favourable times, this is based solely on controlled discretionary spending and dynamic taxation that favors investment and job creation. If a similar path had been followed during the last five years, it would have been possible to generate a fiscal space wide enough for automatic stabilisers to operate freely and efficiently, as well as to develop liquidity injections to solvent companies and families, without having to incur disproportionate levels of public deficit that would generate a marked destabilising effect on our risk premium.

On the other hand, the most recent ECB policy announcements move along the lines proposed by analysts and economists, but at this point it is worth asking whether, after years of unequaled QE, massive injections of liquidity in the European economy, and constant policies of zero and/or negative rates will they really take effect or if they are only a smokescreen to try to calm the markets after unprecedented contractions in recent weeks.

A health crisis such as that of Covid-19, which implies severe restrictions on mobility and, therefore, on production, distribution and logistics — especially on an international scale — is causing and will cause a huge supply shock, by causing major disruptions in value chains, due to the stoppage of production and import of components and intermediate goods. This breakdown of transmission chains, completed by multiple retail businesses closures, will reduce the income of many companies (especially SMEs and micro-companies) to a minimum, while fixed costs will remain intact in the vast majority of cases. This situation will generate a foreseeable increase in the demand for liquidity by companies and families to be able to pay fixed costs and, in turn, hoard some solvency in the face of the present uncertainty. If consumers and companies want to increase their liquidity reserve, this will undoubtedly result in a sharp decrease in consumption and investment, which will lead to a demand shock, amplified by the impossibility of acquiring certain goods or contracting certain services, due to the temporary closure of a multitude of businesses. Therefore, this effect of supply and demand threatens to include the financial sector in its transmission chain, which, to a large extent, has already suffered in recent days due to the flight of many investors with highly volatile assets in these circumstances, such as equities towards liquidity havens.

Even so, the financial crisis that could be unleashed does not derive mainly from the situation of the financial markets, but rather from the risk of non-payment of debt by companies and families, whose only recourse in the face of the sharp decline in income, in many cases, to figure in the available liquidity or “cash.” Consequently, companies may face serious difficulties in paying, not only to employees or suppliers, but also to banks, not to mention the obstacles that many of them will face in the medium term to comply with minimal obligations to creditors (dividends, for example). For this reason, although it may initially seem implausible, the structural crisis that the coronavirus will generate could lead to a global liquidity crisis, since, as in 2008, both the production chains and the financial sector are internationally connected. Therefore, the decrease in liquidity in a given territory or region could cause serious problems in unsuspected areas of the world. On the other hand, it should be noted that this crisis would not be in any case structurally similar to that of 2008 (we are not talking about repercussion or harshness, but rather in terms of form). While that of 2008 was purely endogenous risk, arising from internal weaknesses in the financial sector, that of Covid-19 is exogenous in nature, although some vulnerabilities typical of each national economy may contribute to aggravating it, as argued by Jon Danielsson et al. [19]

At this point, it is worth noting the recently announced injection of liquidity from the ECB of 750,000 million euros, which will be used to purchase both public and private assets under deployment of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP). In addition, the ECB, through said program, has relaxed the requirements for the acquisition of sovereign debt of the States, including the 33% holding limit on the total sovereign debt issued by each member country of the Eurozone, with which it tries to guarantee a constant flow of liquidity. For the moment, said purchase program will last until the end of 2020, and will include each and every one of the asset categories that are part of the asset purchase program (APP). One of the most relevant points is the reduction in credit quality requirements previously needed to acquire commercial paper through BCE programs, which guarantees an ample flow of liquidity.

In this case, monetary policy in the short term will help alleviate certain liquidity problems that result from the interruption of value chains and distribution on a global scale. Even so, this injection will only have an effect on the real economy in the short-medium term; that is, it would cover only the first stages of the theorised liquidity crisis linked to the current and future economic situation. For example, the new credit channels opened by the ECB dedicated to banks to refinance their clients’ debt are similar (although not in volume) to the public guarantee program designed by the Spanish Government to guarantee debt moratoriums. They only lengthen the maturity of the liabilities and add even more weight to the public sector, not forgetting that, ultimately, the financial sector would be rescued, not the citizens.

Recently, some people have tried to compare the ECB’s stimulus program with the one announced by the Fed, when, in reality, the situation of the economy and the American debt markets have practically nothing to do with the Europeans.

Firstly, as Daniel Lacalle [20] pointed out, the Fed’s strategy is mainly aimed at tackling the problems of financing and the lack of liquidity that municipalities may have, to avoid the bankruptcy of many municipalities and to reveal the productive structure of the US economy from within.

A second important line of analysis considers the current real shortage of dollars in the world economy, as dollars posses high value and are the most widely used medium of exchange internationally, both in volume and number of transations. According to certain calculations, the shortage of dollars in global markets would be around $13 trillion (European trillions), derived from the fragility of hundreds of national currencies that, due to their high volatility, do not enjoy the security that investors grant to the dollar.

A third highly relevant factor that has caused and will cause an increase in the demand for dollars and, consequently, a shortage of this currency in the markets, is the maturities of debt issued in this currency, as well as the issuance of new debt in dollars by a multitude of States to face the liquidity shocks generated by Covid-19. Between 2008 and 2019, the value of dollar-denominated bonds by emerging countries would have increased 100%, from 30 to 60 trillion dollars [21], while in 2021 and 2022, approximately 2 trillion of dollars of said debt would expire.

The Federal Reserve plays with a great advantage over the ECB, since the former has thoroughly analysed the existing demand for dollars in the market, increasing in light of the current situation, knowing that any increase in the monetary base will be less than the hole of demand to be covered: a guarantor of the prevalence of the dollar as a medium of exchange and, in part, a refuge for value on a global scale. Meanwhile, the Eurozone’s large trade surplus will most likely collapse during the economic crisis generated by Covid-19, and in the face of massive liquidity injections by the ECB, the euro will completely lose any hint of global power that it could enjoy before.

Conclusion

Europe, the EU and the euro are all in one, a political and economic project that is worth fighting for. In times of tension and need like the current ones, siren songs from the populist extremes tend to arise, seeking to make us believe that we would live much better outside the EU and the Eurozone. They use Brussels as a scapegoat. But, as has been shown throughout this research article, even though the EU and EMU are not perfect projects, the euro has become an absolute guarantor of macroeconomic stability, trade openness, and socioeconomic factor of development for its member countries, that should never be lost sight of. In the face of populism, rationale. In the face of disintegrating forces, cohesion. Europe will manage to conquer the virus and its effects as long as it does not forget that it is very cold outside its borders.

[1] Werner, Pierre (1970), “Report to the Council and the Commission on the realisation by stages ofECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION in the Community”.

[2] Stiglitz, Joseph (2016), “The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe”– W. W. Norton & Company.

[3] Varoufakis, Yanis (2018), “Adults in the Room: My battle with the European and American Deep Establishment”– Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[4] Bagus, Philipp (2012), “The Tragedy of the Euro”– Ludwig Von Mises Institute.

[5] Martín, Álvaro (2019), “Euroescépticos, ¿Quiénes son y que quieren?”-Libertad Digital. Retrieved from https://www.libremercado.com/2019-06-03/euroescepticos-quienes-son-y-que-quieren-1276639361/

[6] Chislett, William (2019), “Spain’s 20 years in the euro: a beneficial straitjacket”- Real Instituto Elcano.

[7] Íbid.

[8] Círculo de Empresarios (2017), “La Empresa Mediana Española”. Retrieved from https://circulodeempresarios.org/publicaciones/la-empresa-mediana-espanola-informe-anual-2017/

[9] Georgescu, B., & Popescu, V. I. (2014). “Optimal Monetary Areas and European Experience”. International Journal of Economic Practices and Theories, 4(6), 1024-1029.

[10] Ratio of the standard deviation of the data to be studied with respect to the sample mean.

[11] IMF International Financial Statistics, Data Tables , Real Effective Exchange Rates- Retrieved from https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61545862

[12] Eichengreen, B., Rose, A., Wyplosz, C. (1995), “Exchange Market Mayhem: The Antecedents and Aftermath of Speculative Attacks”. Economic Policy, 21.

[13] Feldstein, M. (2008): “Will Euro Survive The Current Turmoil?”. The Korea Herald.

[14] Grecia: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/deuda/grecia Italia: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/deuda/italia

[15] Brooks, Robin J, Aasim M Husain, Ashoka Mody, Nienke Oomes, and Kenneth Rogoff. (2004). “Ecolution and Performance of Exchange Rate Regimes” International Monetary Fund Occasional Paper 229.

[16] Rozo, C. (2001), “Protectionism in the European Union: Implications For Latin America.” Intereconomics, Volume 36, May/June 2001, Number 3.

[17] Counting the Cost of EU Regulation to Business, Eurochambres. Retrieved from https://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/costregulation_2009_bis-2009-00286-01.pdf

[18] Erce, A.; García Pascual, A.; Roldán, T. (2020): “El MEDE debe ayudar frente a la pandemia: el caso de España”, EsadeEcPol Insight.

[19] Danielsson, J.; Macaer, R.; Vayanos, D.; Zigrand, J-P., “The coronavirus crisis is no 2008”, Voxeu.org. Retrieved from https://voxeu.org/article/coronavirus-crisis-no-2008

[20] Lacalle, D. (2020), “El plan `ilimitado´de la Reserva Federal anima el rebote”, Invertia, El Español. Retrieved from https://www.elespanol.com/invertia/opinion/20200325/plan-ilimitado-reserva-federal-anima-rebote/477332267_13.html

[21] BIS global liquidity indicators (2020).