After its publication, the General State Budget proposal for 2019, far from clarifying some of the doubts raised, has raised even more questions about the progress of public accounts in the coming months, especially in terms of adjustment to meet the objectives deficit (1.3 percent in 2019). To this is added the difficulty of moving them forward in an environment of extreme fragmentation and parliamentary instability. The numbers presented are based on a remarkably optimistic calculation. They correspond to the Government’s speech about maintaining the current rates of economic growth (although one tenth less is expected: 2.2 percent by 2019) via public spending of a structural nature, with which to offset the decrease in the contribution from the investment and the balance of current operations.

In this regard, the Executive sends the message that it will use the public resources necessary to curb the deceleration phase of the economic cycle. This is not exactly good news, given that no sensible government comes up with such a strategy: to finance expenses of a structural nature, to use resources of a cyclical nature, such as the increase of more than 6 percent in the collection of contributions to the Social Security to cover the increase in pensions, of 4 percent. This only damages the productive structure of Spain, and more with a structural deficit of 2.7 percent of GDP and a primary deficit of 0.5 percent of GDP. Rather, the accounts must be prepared to face future crises (strengthening potential GDP). This implies urgently reaching budget balance, not only cyclical but also structural.

A year after the more than likely recession of Western economies, Spain is approaching it in a very different way from how it entered in 2008. It has gone from twin deficit to twin surplus, given that our economy generates 2 percent of GDP from the balance of current operations: national savings finance investment. However, the only sector that does not create a surplus is precisely the public. In 2018, it subtracted 2.2 percent of GDP from net savings derived from external accounts, which, thanks to the private sector, was estimated at 4.2 percent of GDP.

Without any doubt, one of the most necessary points is the stabilisation of the level of public debt on GDP (debt-to-GDP ratio) and its subsequent reduction. The two key factors to achieve this are the generation of a primary surplus above 2 percent of GDP, and a nominal growth rate higher than the cost of financing. The variable in which the Government can act with enough autonomy is the first, and more having reached the minimum level of cycle in the interest line of the debt. Since a decrease in the level of debt has not been achieved in the “peak” of the cycle, it is essential to make significant adjustments to public spending with which to achieve said primary surplus.

However, in the budget proposal presented, it does not appear that desire to deepen the stability of public accounts, but quite the opposite: to the Government, after having failed to approve the relaxation of the deficit targets (0.5 percent of GDP), there is no other choice but to comply with the resignation of those recorded in the 2018 Budget. Since it is intended to raise the structural expenditure —the sum of the measures contemplated in the agreement with Podemos amounts to 5,730 million euros in a single year , of which 95 percent will end up being of this nature— and since the agreement with Brussels must be fulfilled, the Executive has chosen to launch a series of ad hoc tax increases. Among them, there are new tax figures, on which almost half of the additional collection rests, estimated at 7.2 billion euros.

This leads to an obvious credibility problem in the numbers presented, for a number of reasons: (i) It is unwise to rely on the financing of a real expense to a set of new taxes, on whose implementation and results there is total uncertainty. (ii) Estimate the collection that a new tax may generate is nothing more than a science fiction exercise, which has a very high probability of deviation from the expected figure. (iii) The Government of Sanchez follows in the wake of Rajoy’s when preparing an income forecast based on an elasticity of fiscal income over totally unrealistic GDP (the nominal GDP estimate is 3.8 percent for 2019), away from historical average value, by which, increases of 1 percent of nominal GDP represent increases in tax collection of 1.06 percent, which, in the case of personal income tax, increases to 1.3 percent (ECB Working Paper 1989, January 2017 ). (iv) The legality of taxes such as digital, the one that taxes financial transactions, or the limitation of the deductibility of dividends from foreign subsidiaries in the Corporation tax, entails serious doubts if they are not articulated under the umbrella of a community legislation.

In sum, the published figures worry more than alleviate, by feeding legal insecurity and confusion, even among the community authorities themselves. Not surprisingly, the structural adjustment requested by the European Commission is renounced, which also strongly criticised the Stability Program Update when it was presented. This is completely unacceptable in an economy that has the dubious merit of having the largest public, primary and structural deficit in the entire Eurozone. By maintaining it, the basic objective of exiting the Excessive Deficit Protocol (PDE, in Spanish) is being jeopardised. That, and not another, would be the way to prepare public accounts for the next recession in an environment of interest rate rises (the ten-year Spanish bond is very likely to be around 2 percent).

Budget adjustment plan: a proposal

Thus, the publication of the General State Budget proposal for 2019 has led to the finding that the budget consolidation process and the commitments acquired before the European Commission are not going along the planned path of substantial reduction, moving away from the deficit ceiling of 3 percent on GDP. The gap between income and expenses is close to the objectives set for the whole year, despite the fact that the Spanish economy maintains growth rates in the environment of 2.5 percent.

The danger of noncompliance with the agreed objectives (1.3 percent of GDP, after not being able to approve a new deficit path) urges the approval of an ambitious budget adjustment plan. This has to coincide with the next electoral calls and lay the foundations for adequate preparation by the Spanish economy and public accounts before the most likely recession that will come from the third/fourth quarter of 2020.

Taking the last comparable data of 2018, we observe how, between 2019 and 2020, the public deficit should fall from around 2.8 percent in which it will foreseeably close 2018 (with the budget execution to the month of October, the public deficit amounts to 2.94 percent of GDP) to the target of 1.3 percent in 2019. This implies an adjustment of 1.65 GDP percentage points: almost 20,000 nominal million euros.

Of these (from now on we will handle them in round figures), some 18,000 million would come from an adjustment of income and expenses by the Central State Administration, the Autonomous Organizations and Social Security. The remaining 2,000 million would come from the Autonomous Communities. The detail of the adjustment is as follows:

General State Administration + OO.AA + Social Security

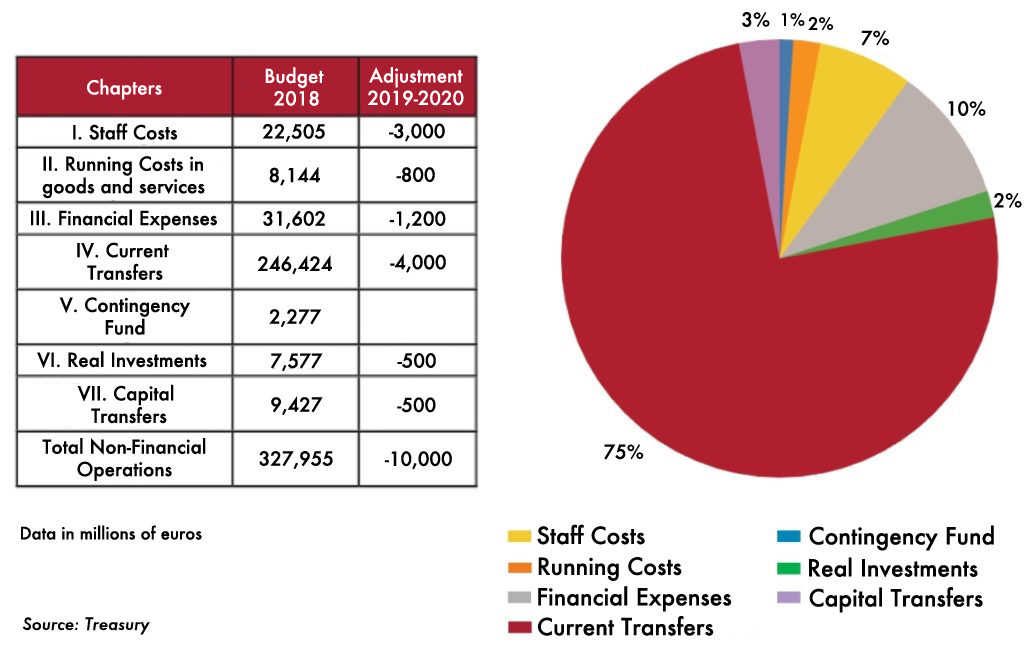

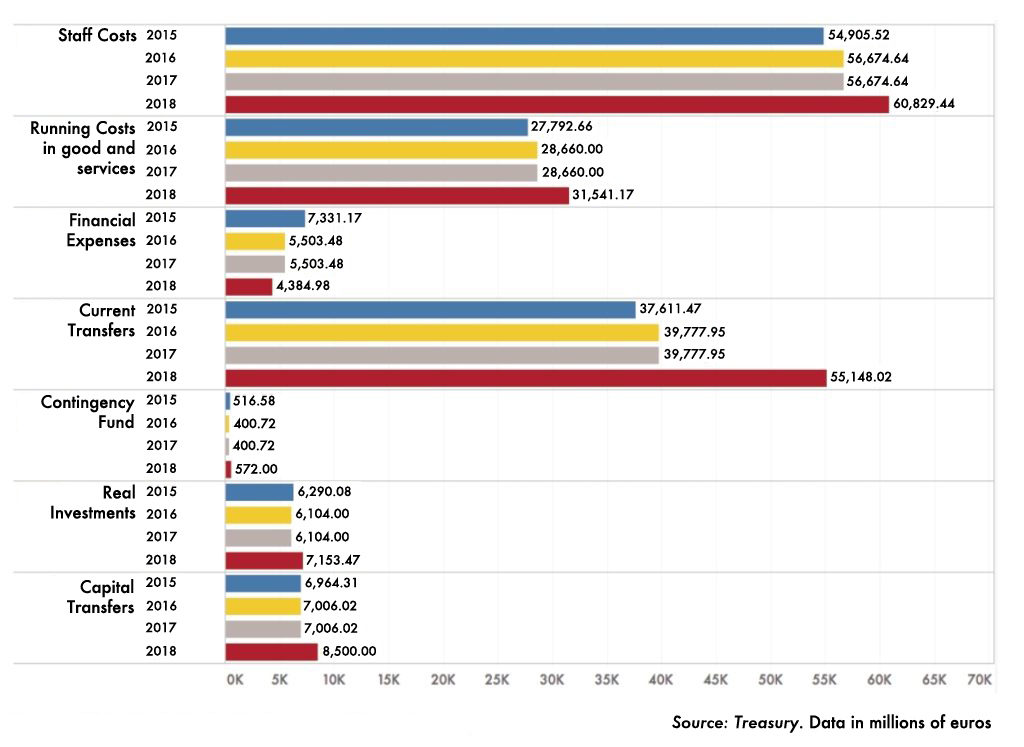

a) Adjustment of consolidated non-financial expenditure

Two chapters would fundamentally support the cut in expenses: the first, «Personnel expenses», with a decrease of 3,000 million euros that would dampen the effect of salary increases agreed in the last two years. It would be achieved by reducing non-public employment and the number of senior positions.

On the other hand, the adjustment would rest on Chapter IV of “Current Transfers”, applying a cut to the funds allocated to the Autonomous Communities. This would have to be estimated at 4,000 million euros, and would be implemented through a lower expense charged to the liquidations of the autonomous financing system. Perhaps the most problematic point lies “where” the Autonomous Communities are going to reduce, since the State has no powers to force them to adjust, within their budgetary autonomy, some items or others. Therefore, it is foreseeable that these will involve easy expenses and that few want to undertake real reforms in important disbursements, such as the contracting of goods and services or the centralization of purchases of surgical, sanitary, educational or pharmaceutical material. In this regard, it should be noted that the majority of current transfers correspond to pensions, which have a worrying growth path. This can only be corrected by canceling the delay until 2023 of the entry into force of the sustainability factor, as well as by recovering an annual revaluation rate much lower than the CPI, closer to 0.25 percent with which they have been been updating until 2017.

Also, it would be convenient to expect a simultaneous reduction in Chapter III of “Financial expenses” or interest on debt, which would remain close to 30,000 million in 2020 (thanks to a contraction of 1,200 million). It would be achieved through a debt issue with lower interest rates (the outstanding debt balance has a lower interest burden), since they cause an accelerated fall in the average interest rate of the outstanding debt, in addition to a lower financial cost for refinancing debt at maturity.

Ending the expenditure items, a saving of 800 million would be achieved in Chapter II through a rationalisation plan for the Administration’s expenditure (with special emphasis on Social Security and Autonomous Organizations). They are also subject to two separate cuts in public investment items (Chapter VI) and subsidies (Chapter VII) of 500 million euros each.

Graph 1. Breakdown of expenses and proportion

b) Increase in income

In the income chapter, one of the most necessary exercises is to transcend the common places, such as the fight against fraud, since it does not generate only effective collection: income is recorded by accrual criteria and, therefore, what is obtained for pursuing fraud, it is intended to cancel previous accounting notes.

In this way, most of the increase in income comes from direct taxes (personal income tax, companies, …), with a strong cyclical component of 7,000 million euros (mainly Social Security Contributions and Personal Income Tax). The rest comes from the indirect ones, especially the environmental tax and Special Taxes, for an amount of 1,000 million euros.

Graph 2. Breakdown of income and proportion

How Autonomous Communities are financed depends mostly on the resources that the central government is able to collect via taxes, and which, subsequently, distributes according to certain economic and social criteria established in the Organic Law of Financing of the Autonomous Communities.

Thus, the Autonomous Communities receive money remittances periodically, in the form of the advances that correspond to them each year based on the expected collection, which is included in the General State Budget Law. Later, after the expiration of the year, the liquidation proceeds, which takes stock of how many advances each Community has received and what amount it should receive to finance the transferred public expenditure. In this way, if the advances are higher than the financing that they have, they will have to proceed to return what they have received and, if it is the contrary, they will have the right to receive more funds until they cover what is necessary.

Given the mechanism of the autonomous financing system and the scarcity of sources outside the transfers of the Central State (85 percent of the tax revenues of the Autonomous Communities come from it; and only 15%, of taxes ceded entirely and levies own), and because of the dependence on the concept of “expected collection”, if there are no Budgets for 2019 and those of 2018 are extended, the operation of regional finances would be greatly hindered. In the absence of a reliable estimate of the 2019 revenues, there would be no adequate guide with which to design the advances that the Autonomous Communities would receive to finance public services.

Nor would we have a clear vision of what will happen with a liquidity support instrument: the Autonomous Liquidity Fund (FLA in Spanish), whose endowment also depends on the General State Budget, specifically Chapter VIII of Financial Assets. In 2019, resources deposited in extraordinary liquidity funds will be theoretically reduced (if the Budget is approved) by 4,000 million euros compared to 2018.

Given the «budget closure» of all non-committed expenses, the FLA was the way out of the autonomous communities to obtain money. In case the Budgets are not approved, and in case of an eventual extension of those of 2018, they, if they want to access this financing, will have to do so by means of an extraordinary credit of other expenditure items, already blocked to reach the deficit targets.

Of the 2,000 million adjustment that should be undertaken, 500 would come from Chapter I (Personnel expenses), through a resizing of the public workforce and the non-hiring of more employees. In fact, we should say goodbye. In Chapter III (Financial expenses), the cut would amount to 500 million, from savings in interest on the debt, both for the intervention of extraordinary liquidity mechanisms and for the reduction of bank loan financing costs. As for the most important item (1,000 million), it would belong to Chapter IV of Current Transfers. This is the favorite tailor’s drawer of the Autonomous Communities, which will stop everything they usually justify as «social spending». However, what it groups to a large extent are subsidies and financing of activities that are expendable, such as representations abroad, inefficient public bodies, or aid that should not be delivered.

Graph 3. Breakdown of expenses of the Autonomous Communities

Conclusion

Given the current situation of the economic cycle and the evolution of the advanced indicators, the main priority in fiscal policy should be to prepare the public accounts in an adequate manner to enter the best possible conditions in the next crisis. This will probably arrive between the third and fourth quarter of 2020.

The Spanish economy cannot afford to face the recession phase of the cycle with a cystic structural deficit above 2.5 percent of GDP. Moreover, having enjoyed the best financial conditions of the last decades to reduce both their financial costs and the structure of maturities and types of living public debt.

Therefore, it is necessary to reformulate the public accounts presented, and move forward in the direction marked by the proposal described in this document: undertake an early budgetary adjustment taking advantage of the growth of short-term income that will occur again in 2019.

References

Proposal of General State Budgets for 2019. de Presupuestos Generales del Estado para 2019. Spanish Treasury

Sanmartín, J. (2007), “El efecto de los cambios en los tipos marginales sobre la base imponible del IRPF”, Spanish Treasury, 182 (3): 9-27.

Sanz, J.F. (2013), “¿Es la subida de los tipos marginales rentable en términos recaudatorios? Caracterización de la curva de Laffer del IRPF español”, (mimeo).

Sanz, JF., & D. Romero (2012), “Evaluación del impacto recaudatorio de las reformas de IRPF e IVA de 2012 en un contexto de crisis económica”, Papeles de Economía Española, nº 133: 39-48.