How long do you work for the State?

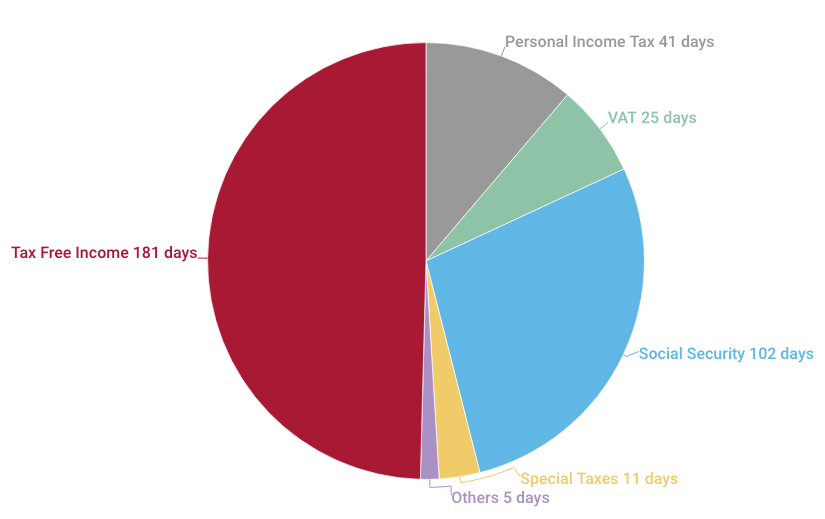

On July 3, Spain celebrates its 2014 Tax Freedom Day. In other words, Spanish workers need 184 days to fulfill their tax obligations. The Tax Freedom Day is the date on which citizens would have generated enough income to pay all taxes. From then on, they start generating income for themselves. The Tax Freedom Day translates the tax effort into the number of days that workers need to pay their taxes (direct and indirect) and Social Security contributions. A Spanish worker with an average salary of 24,400 gross euros per year would spend 102 days to pay Social Security contributions, 41 days to pay personal income tax, 25 VAT, 11 special taxes and 5 other taxes. In total, he would dedicate 184 days of his work (15,988 euros) to the State’s expenses.

Tax opacity

What most workers are unaware of is that the company pays the Social Security authority the equivalent of 84 work days; 7,296 euros above the gross salary. This means that the real value of the worker —or the labor cost for the company— actually amounts to 31,696 euros.

The Tax Freedom Day remains at maximum levels

Despite some tax adjustments, over the last year there have been no significant tax increases, so this year the Tax Freedom Day will be celebrated on the same day as in 2013. However, the tax increases of the last 4 years set the Tax Freedom Day at record highs. The tax increases will have resulted in a total of 9 work days and a cost of 747 euros per employee: 116 euros attributable to income tax increases (state and regional), 193 euros corresponding to the 2010 VAT increase, 370 euros to the increase from 2012 VAT and 68 euros to other taxes such as Real Estate Tax (IBI), Circulation Tax or special taxes (gasoline, electricity, alcohol, etc.).

Graph 1. What does your working day translate into?

Tax effort and income level

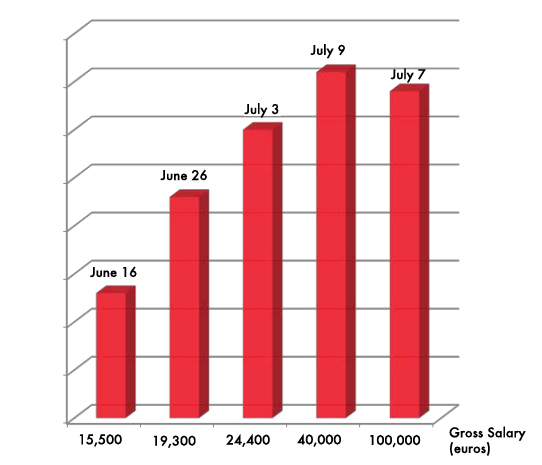

To analyse the tax effort based on income, five scenarios have been taken into account: (i) a person who earns 15,500 euros (the most common salary in Spain); (ii) another that earns 19,300 euros (the median salary, which divides the number of workers into two equal parts, those with a higher salary and those with a lower salary); (iii) an average income of 24,400 euros; (iv) a salary of 40,000 euros; and (v) another of 100,000 euros.

Each of these individuals has different personal situation and consumption habits. As can be seen in the graph, the tax effort grows with the gross salary: from June 16 for an income of 15,500 euros to July 9 for an income of 40,000 euros; 23 days difference between a 1,000-euros-a-month and a wealthy worker. Moreover, from a certain level of income, as Social Security contributions have a maximum limit, the tax effort of workers is reduced by two days, from July 9, in the case of a person who earns 40,000 euros, to July 7 for a person with a gross salary of 100,000 euros. The explanation of this behaviour is detailed in the following section on labour taxation.

Taxation of labour

Salaries in Spain are three times taxed with Income Tax, Social Security paid by the worker and Social Security paid by the employer. Social Security consists of a tax that the State tries to disguise or hide from the taxpayer since it does not appear in its entirety on the payroll. The Social Security contributions made by the employer multiply by five times the withholdings that are applied directly to the payroll of the average worker and become a hidden part of our payrolls. However, Social Security contributions can be considered as one more tax, since all the money goes to a common fund from which the pensions of today’s retirees are paid and they do not represent real insurance for the current taxpayer.

Graph 2. Tax Freedom Day according to income level (2014)

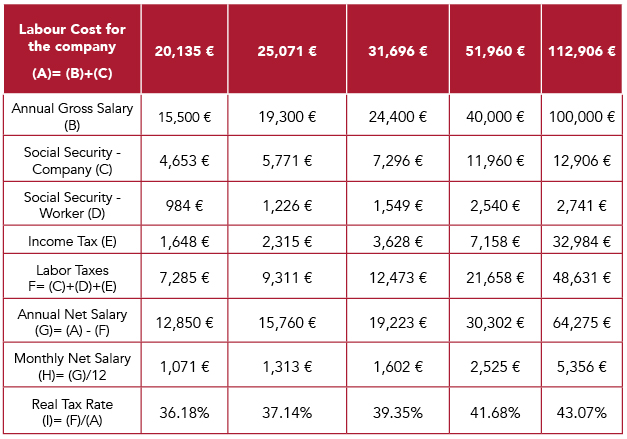

As we know, social security contributions have a single tax rate in Spain. It is not a progressive tax such as the personal income tax. In addition, no deductions are made depending on the level of income, so that, even for the lowest income, the rate that is applied is the maximum rate of 36.25 percent: 29.9 percent is paid by the company/employer and 6.35 percent by the employee. However, these contributions have a maximum limit: all income that exceeds from 3,597 gross euros per month (43,164 euros annually) only pay up to this level, so that no taxpayer can contribute more than 15,647 euros per year to the Social Security.

As a result, higher incomes benefit from this system. At the same time, the existence of this ceiling poses another problem: for the employer, without a doubt, it is cheaper to raise the salary to those workers who earn more than to the lowest incomes, thus increasing the number of the latter and sharpening, increasingly, the possible differences between social classes. To analyse the taxation of income, the previous five scenarios have been taken into account: a person who earns 15,500 euros (the most common salary), another who earns 19,300 euros (the median salary), an average income of 24,400 euros, a salary of 40,000 euros, and another income of 100,000 euros.

Table 1. Taxation of labour in Spain

For each of these cases, the corresponding income tax, the social security contributions paid by the company and the social security contributions paid by the employee have been calculated. The labour cost for the company or the total gross salary formed by the worker’s annual gross salary plus the Social Security contributions paid by the company has also been calculated, as detailed in the table. Once the total tax on the income of the work is derived, the real tax rate (tax wedge) applied to each of the five cases has been calculated.

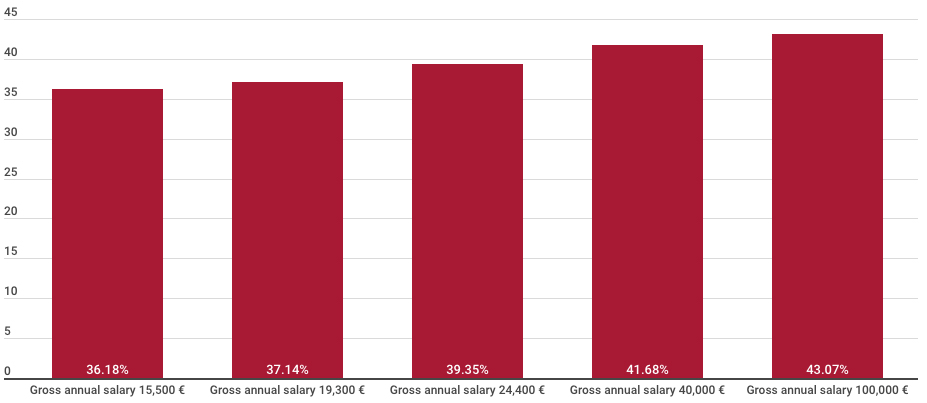

Progressiveness in Spain is less than 7 percent

The real tax rate for a 1,000 euros -a month- employee is 36.18 percent, 39.35 percent for a net salary of 1,600 euros and 43 percent for one of 5,400 euros. These results reveal that the progressiveness in labour taxation is reduced to only 7 percent. Thus, it is of little use that there are CCAA like Navarra that have up to eleven tranches of income or that the tax rates range from 13% (Navarra) to 56% in some CCAA if in the end this difference of 43 percentage points It is reduced to a real differential of 7 points.

Graph 3. Real tax rate according to income level

For this same reason, different OECD studies, including the Taxing Wages 2014 report, reveal that beyond a certain level of income the system is regressive. That is, comparatively, low and medium incomes pay considerably more taxes than higher incomes.

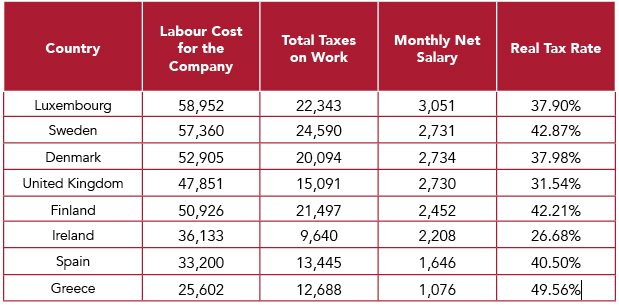

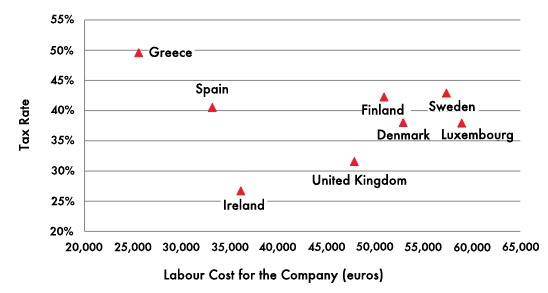

If we analyse the situation of the Spanish worker in the context of the European Union, we can see how the tax rate applied here (40.5 percent) on a net income of 1,650 euros is similar to that applied in countries such as Sweden or Finland. However, a crucial difference should be noted: the average salary of these countries reflected in the table is 70 percent higher than the income of a Spanish worker. However, we also have the example of Greece which, with a lower income level than ours, applies a tax rate of 49.56 percent —eight points above 41.6 percent corresponding to 2013. On the other hand, countries such as Ireland or the United Kingdom, with higher average income levels than Spain, tax income at much lower tax rates than ours: 26.68 percent and 31.54 percent, respectively.

Once again, Spanish taxation is evidenced by taxing average and low income well above the corresponding level. But high incomes are not saved either. According to the latest Taxation trends in the European Union report, Spain is one of the countries of the European Union in which the maximum rate of income tax is higher (56 percent), at the same level as that of Denmark (55.6 percent) or Portugal (56.5 percent) and only surpassed by Sweden (56.9 percent).

Table 2. Labour taxation in Europe (2014)

The maximum rate of personal income tax applicable at this time in Spain is 56 percent, although not all autonomous communities have chosen to raise it to this level. In the rest of the world, according to a 2012 KPMG report, only Aruba (59 percent) has a maximum income tax rate higher than the Swedish one.

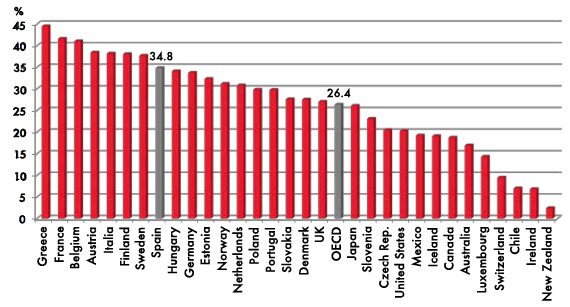

Taxation of OECD countries

According to the Taxing Wages 2014 report of the OECD, in 2013 the tax pressure on the average income in Spain (40.7 percent) was five points higher than that of most member countries (35.9 percent average for the OECD), standing in fourteenth place. In addition, Spain stands out as one of the countries with the highest progressiveness in the first three levels of income and reduced progressiveness for higher incomes. The low progressiveness for higher incomes is mainly due to the existing social security ceilings.

The study also analyses the tax pressure that couples with children endure in each of the countries based on the level of income. According to this study, after the latest increases in tax rates in Spain, couples with children and a single salary withstand a tax pressure well above the OECD average (8.4 percent) and Germany (1 percent). In addition, in countries such as Germany, families with children receive about 180 euros per month per child as a family allowance and benefit from a reduction in the taxable amount for dependent children of over 7,000 euros per year.

Over the last four years, this group of taxpayers (with dependent children) has been the most punished for the tax increase in our country.

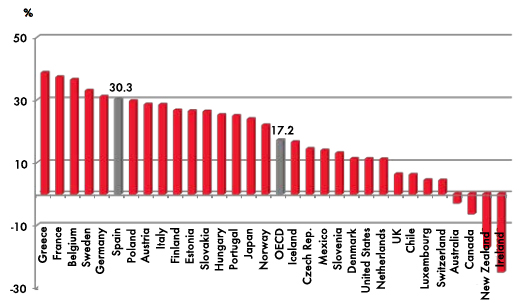

Graph 4. Real tax rate

In the case of a single-parent family with children and an income that does not reach 70 percent of the average salary, the tax pressure doubles the average of developed countries: 30.3 percent in Spain versus 17.2 percent, which is the average of OECD countries.

It should not be forgotten that, given the design of the pension system in Spain, it is these families with children that will support it in the future. They cannot be «taxed» and pretend to save money to offer a good education to their children; a sine qua non condition for high salaries capable of covering the huge expenditure of pensions. The report also analyses the evolution of tax pressure in the last twelve years. Between 2001 and 2013, Spain shows a different trend since tax pressure grows well above the OECD average, regardless of income level or family situation.

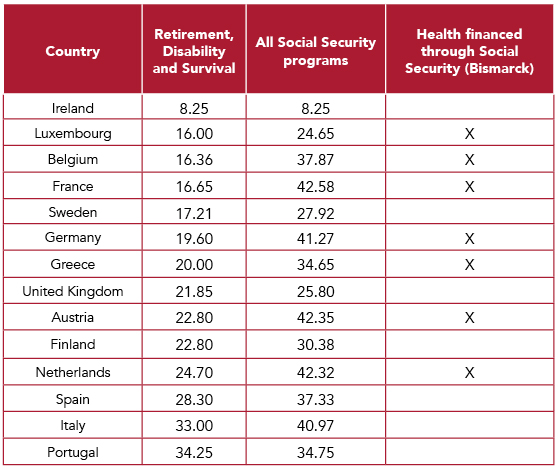

Spain is the country of Europe with the highest Social Security contributions

Apart from the income tax, social security contributions also contribute to making the tax effort of Spanish workers so high. Although all European countries have a Social Security system, the benefits offered are not always the same. The most significant case is that of health financing, since in some countries (such as Spain) it is financed through taxes (Beveridge model) or through social insurance (Bismark model). Therefore, when comparing Social Security contributions, the benefits of each system must be taken into account.

Graph 5. Tax wedge: Couple with children and a salary

If we only take into consideration the type of contribution that covers retirement, disability and survival, Spanish workers and their companies are the ones that contribute the most to the Social Security system (28.3 percent), only behind Italy (33 percent) and Portugal (34.35 percent). In contrast, in Germany, France, Sweden and Belgium, prices fluctuate between 16 percent and 20 percent, between 8 and 12 points below Spain.

However, when considering the set of contributions for all Social Security programs, Spain moves from third to seventh position. Thus, in Spain the contributions reach 37.33 percent of the gross salary, while in Germany, France, Austria and the Netherlands, contributions move between 41 percent and 42 percent. However, this difference is due to the way of the Healthcare system is funded. In Spain, Healthcare is financed through taxes, while in the other countries mentioned it is mainly financed through Social Security.

In Spain there is a false belief that Healthcare is also financed by Social Security. However, Social Security first entered into crisis in 1978, the year in which it stopped financing unemployment benefits and shortly thereafter healthcare. Since the approval of the General State Budgets of 1999, the financing of the National Health System (SNS) is completely separated from Social Security and is now financed through direct and indirect taxes. The system is financed, to a greater or lesser extent, by all its potential users, since VAT and special taxes are paid by all citizens, regardless of their legal or employment status. Therefore, the messages that associate the right to health with Social Security contributions, try to encourage social insolvency, suggesting that some people take advantage of the system.

Graph 6. Tax wedge: Single parent family with children

Table 3. Types of contributions for social security programs

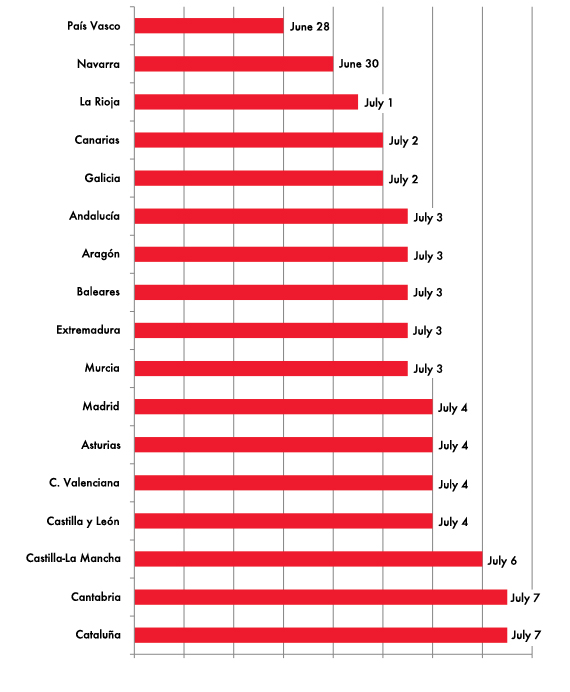

Tax Freedom Day by Autonomous Community

Although the Spanish Tax Freedom Day average is July 3, the tax effort varies from one Autonomous Community to another. Currently, there is an arc of up to 9 days between the Basque Country (the Autonomous Community with the lowest tax effort) and Cantabria and Catalonia (the two Autonomous Communities with the highest tax effort). For an average Spanish citizen, living in Catalonia or Cantabria would cost 9 more days of work per year and 737 euros extra compared to a resident of the Basque Country. The reason for this difference is due to the fact that in Cantabria and Catalonia the Real Estate Tax is well above the average.

In addition, the Circulation Tax, the Retail Sales of Hydrocarbons and the Income Tax are also generally higher in these two autonomous communities. In contrast, in the Basque Country, the tax freedom day is celebrated 7 days before the national average date. This difference is due exclusively to the income tax, so that the Basques save 468 euros in income tax thanks to their regional regime. As in the Basque Country, in Navarra the tax freedom day takes place at the end of June, 3 days before the national average. In the case of this autonomous community, the difference is due both to the Personal Income Tax (in Navarra, employees pay 181 euros less than the national average) and to a lower municipal tax burden through taxes such as IBI. In addition, Navarra has once again eliminated the regional tax on the Retail Sale of Hydrocarbons.

With the aim of creating a guide thanks to which the citizen can know in which community it is more advantageous to work, the national average income has been used as a reference to calculate the Tax Freedom Day of each autonomous community, instead of the average salary of each region. This should also serve to stimulate tax competition between autonomous communities, so that they offer a more favourable treatment to the taxpayer —even in those taxes that have less ‘electoral cost’.

One of the reasons that require calculating the existing regional differences for the same salary level is to avoid the belief that in the richest regions —where taxpayers pay more because they charge more— higher tax rates are applied. Thus, the comparison results in equal conditions.

To calculate the Tax Freedom Day in 2014, the same salary was used as in 2013 and 2012 so that the results can be comparable.

Graph 7. Tax Freedom Day by Autonomous Community

2014 brings few tax developments

In this edition, the most remarkable thing is the position that the Autonomous Communities have taken in relation to the Tax on Retail Sales of Hydrocarbons: Andalusia, Catalonia and Galicia raise the autonomous rates to the maximum (4.8 cents per liter). Instead, following the recommendations of the Tax Freedom Day 2013 Cantabria reduces it by half (2.4 cents) and Navarra eliminates it. Thus, there are four autonomous communities that have not applied the ‘sanitary cent’ in 2014 (La Rioja, Aragón, Navarra and the Basque Country). On the other hand, Madrid and Cantabria have established a more moderate tax and the rest of the Autonomous Communities have harmonized it upwards. It is also important the decline in personal income tax initiated by some autonomous communities for middle income and that has been a real scourge to the tax policy of the current central government.

The autonomous communities whose tax policy has resulted in a de facto reduction of the average Income Tax have been: Galicia (where the average worker pays 58 euros less than last year), Madrid (with a saving of 56 euros), Extremadura ( 26 euros), Álava (62 euros), Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya (25 euros) and Cantabria (9 euros). As far as municipal tax policy is concerned, it can be observed that public opinion has been able to influence the reduction of local taxes that are too high. Instead, mayors who have not been pressured by their voters have chosen to raise taxes. In 2014 the Circulation Tax was increased in Valencia, Santacruz de Tenerife (Canary Islands), Mérida (Extremadura), San Sebastián, Vitoria, Bilbao (Basque Country), Madrid and Pamplona (Navarra).

Thus, the Circulation Tax is still high in San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa), Bilbao (Vizcaya) and Vitoria (Álava), followed by Madrid, Oviedo (Asturias), Santander (Cantabria), Valladolid (Castilla y León) and Palma de Mallorca (Balearic Islands). On the other hand, having a car is cheaper in Pamplona (Navarra), Mérida (Extremadura), Santiago de Compostela (Galicia), Logroño (La Rioja), Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Canary Islands), Seville (Andalusia) and Valencia.

Another local tax, of the utmost importance for municipalities because of their collection power is the Property Tax (IBI). In 2014, some municipalities have chosen to raise the IBI, either through the cadastral value, or through the rate: Madrid, Pamplona (Navarra), Bilbao and San Sebastián (Basque Country), La Coruña (Galicia) and Toledo ( Castilla la Mancha). Instead, the municipalities of Seville (Andalusia), Oviedo (Asturias), Mérida (Extremadura) and Santander (Cantabria) have decided to lower the IBI. In this regard, it should be noted that the last report of the Tax Freedom Day 2013 put this last city hall under magnifying glass and the results have not been expected.

Principles of a good tax system

Albert Einstein said that the most difficult thing to understand in the world is the income tax. This is not surprising if we take into account the way in which tax systems are designed in some countries. Already in the eighteenth century, Adam Smith traced the general principles for a good tax system in The Wealth of Nations. First, proportionality: each person should pay a proportional percentage (not progressive) of their income, complying with tax equity. In addition, taxes should be predictable; that is, not arbitrarily set, avoiding the exemptions and deductions established according to the source of income or other factors.

The system should not create incentives to avoid taxes (see the ‘Depardieu case’) and it has to be simple to minimise the cost of collection. According to the Paying Taxes 2013 report, in Spain, a company dedicates 167 hours a year to pay taxes: approximately one month of work to comply with tax requirements. The study reveals that reducing the complexity of the tax system would raise GDP, on average, 0.5 percent. Switzerland and Luxembourg are the European countries where fewer hours are spent to pay taxes: 59 and 63 hours respectively. That is, three times less than in Spain. A good system is also characterised by tax pressure that does not discourage work and investment. In addition, it should not encourage certain groups to try to obtain tax benefits from the hand of the rulers.

Transparency, neutrality and simplicity

The US-based Tax Foundation also establishes a guide on the characteristics that any tax should meet: It is all about transparency, neutrality and simplicity.

Social Security contributions paid by the employer which do not appear on the worker’s payroll are the best example of tax opacity. The income tax in Spain, with 11 income tranches, has tax rates that range from 13 percent to 56 percent, plus regional and state deductions, which make this tax the antonym of tax simplicity. Stability is another important characteristic to respect, which means that tax policy should be consistent and maintained in the long term. In addition, changes cannot be retroactive as has been the case in the application of the real estate tax.

In fact, taxpayers have to be confident, rely on the legislation in force when they sign a contract or make a transaction. The tax system should have broad tax bases, so that the tax rates can be moderated (see VAT) and, finally, the system should not restrict free trade. If a single tax rate for VAT were applied in Spain, it could be well below the current 21 percent and would also help to eradicate tax fraud.

Summary and conclusions

The tax burden borne by taxpayers in Spain varies depending on the level of income, consumption habits and the autonomous community in which they reside. Therefore, although a Spaniard works on average until July 3 to pay all his taxes, this average hides important differences from one autonomous community to another or from one level of income to another.

For the calculation of the Tax Freedom Day, instead of taking the average salary of each region, the national employer has been used with the objective of creating a guide for the taxpayer to know in which community it would be convenient to reside in the hypothetical case of to be offered the same salary. If only the percentage of taxes paid in each territory is analysed, one might think that those communities that have higher incomes are also those with higher taxes, which is false.

At the same level of income, with similar personal circumstances and consumption habits, differences from one community to another can represent up to 9 work days. These are mainly due to the Property Tax (IBI), a municipal tax that varies greatly from one municipality to another. The same applies to the Circulation Tax, higher in cities such as San Sebastián, Bilbao, Vitoria, Madrid, Oviedo, Santander, Valladolid or Palma de Mallorca.

To a lesser extent, personal income tax also influences the tax burden. Navarra and the Basque Country are the two communities that have always used their tax regime to tax work income below the national average. Other communities such as Madrid, Extremadura, Galicia or La Rioja, for example, have also used the income tax regional tranche to reduce tax rate to different income levels. In contrast, Catalonia, Andalusia and Asturias have used the regional tax to punish higher incomes. Autonomous communities have also applied different family minimums or regional deductions that benefit both single-parent families with several dependent children and large families. Another tax that the communities have applied and that has given rise to differences in the tax burden is the so-called ‘sanitary cent’. Aragon, La Rioja, Navarra and the Basque Country are the four regions that have distanced themselves the most from the rest by not applying this regional surcharge to the sale of fuels.

The report also analyses the tax freedom day for different income levels. The results reveal that there is a 23-day difference between a 1,000 euros-a month-worker and a well-off worker. However, once a certain income threshold has been exceeded, the tax effort is reduced, first by Social Security contributions and then by the consumption tax.

The Value Added Tax (VAT) is a tax that, despite having different reduced rates, makes the tax effort of those low incomes that dedicate all their income to consumption be greater than the tax effort of the well-off families, since the latter can allocate part of their income to savings, and therefore, the VAT is not applied to that part.

The analysis of the tax effort made by employees of the different regions reveals that the autonomous communities have sufficient tax tools to modify the tax burden borne by taxpayers through autonomous communities’ and municipal taxes. This way, tax competitiveness is encouraged and it is possible to analyse whether a lower or higher level of tax effort can serve to revive the economy and employment. However, in the economic crisis of recent years, many autonomous communities have used their ability to regulate certain taxes to increase the tax effort. It should not be forgotten that autonomous communities such as Navarra or the Basque Country, which historically have had a tax pressure on income below the Spanish average, have also enjoyed lower unemployment rates. When analyzing labour taxation, it has been seen how the average Spanish income is taxed at the same level as in Sweden or Finland, despite the fact that the average salary of these countries is 70 percent higher and that the wealthiest families pay taxes in the personal income tax at the highest tax rate in the world —only behind Aruba and Sweden.

We have also observed how 60 percent of taxes on income are hidden and do not appear on the worker’s payroll. These are the Social Security contributions paid by the company, money that represents an important expense and that influences the worker’s salary. In fact, in Spain the total Social Security contributions are between 8 and 12 percent higher than the contributions made in countries such as France, Germany, Sweden or Belgium.

In addition, it is these same contributions that have a unique rate and a maximum cap that make progressiveness get reduced from 43 percent —as stipulated in the personal income tax— to a real differential of only 7 points. Thus, the more complex the tax system is, the less it serves to achieve the objective for which it has been designed. For this reason, the tax reform has to start by including in the gross salary the Social Security contributions by the company and merging them with the worker’s contributions to reflect the real tax burden. The State takes more than half of the income of workers but does so in a disseminated way so that the taxpayer is not scandalized.

Methodology

The Tax Freedom Day translates the tax pressure into the number of days that taxpayers need to cover their tax obligations. It is the date of the year in which a person has generated enough income to pay all their taxes. From then on, taxpayers stop working for the State and starts earning money for themselves.

Tax Freedom Day takes into account the income tax, Social Security contributions by the worker and direct and indirect taxes: VAT, Real Estate Tax, special taxes (on alcohol, tobacco, electricity, hydrocarbons …), circulation tax, retail sales tax of certain hydrocarbons, the Property Transfer Tax (ITP) and Documented Legal Acts (AJD), etc.

To calculate the income tax, the different regional tables, the reductions for work income, the personal and family minimums and the different regional deductions of the full quota by large family have all been taken into account. For the calculation of the IBI, three types of dwellings located in the capitals of the autonomous communities have been used. The assignment to each user (who has home ownership) of one of the three types of housing is made based on the level of their annual gross income.

In case of not having data for the capital city or another important city of a given Autonomous Community, the national average is used instead. For the Circulation Tax a car of between 12 and 16 horses has been considered. For motorcycles, an average quota has been calculated for both those with less than 500CC and those with more than 500CC. Since the circulation tax is a municipal tax for each community, the tax applied to the capital of the region has been taken into consideration. In the case of beer, one of 330 ml has been used as a unit, with a volumetric alcoholic strength greater than 2.8% vol. and a dish grade lower than 11.

With respect to the alcohol tax, a glass of 20g of pure alcohol has been taken as a standard unit. For the tobacco tax, the average sale price of cigarettes has been used instead of the maximum retail price for each brand. To calculate this average, the statistics of the Commissioner for the Tobacco Market of the Ministry of Economy and Finance have been used.

In the tax on hydrocarbons, a distinction is made between gasoline and diesel. The average sale price in Spain has been taken. The regional type has also been taken into account.

For VAT, the costs that impact VAT are calculated first. The VAT supported is calculated differently according to the level of income, based on the distribution of household expenditure by expenditure groups and tax rate.

To determine the tax freedom day in each Autonomous Community, a married person has been considered, with a child in charge of the two parents and with a gross income of 24,400 euros. The taxpayer manages to save 1,000 euros a year, has property and car housing, so 200 euros are spent on gas per month. Also, smoke half a pack of cigarettes and drink 7 beers and two drinks a week. Monthly electricity bills reach 50 euros. The arithmetic average of what a taxpayer who earns 24,400 euros (the average salary in Spain) in the above mentioned situation would pay in each of the autonomous communities has been calculated to determine the tax release day for Spain. As for the results, the Tax Freedom Day has been calculated considering only the Social Security contributions by the worker. However, once the contribution to Social Security has been introduced by the company, the tax freedom day is significantly delayed until the middle of the year.

References

European Commission (2014), “Taxation trends in the European Union”, Eurostat Statistical Books

James Rogers & Cécile Philippe (2014) “The Tax Burden of Typical Workers in the EU 27”, New Direction

KPMG International (2012). “KPMG’s Individual Income Tax and Social Security Rate Survey 2012”

OECD (2012), “Taxing Wages 2011”, OECD Publishing. Paturot, D., K. Mellbye and B. Brys (2013), “Average Personal Income Tax Rate and Tax Wedge Progression in OECD Countries”, OECD Taxation Working Papers, No. 15, OECD Publishing.

PWC (2014), Paying Taxes 2014

OECD (2014). “Trends in Personal Income Tax and Employee Social Security Contribution Schedules”, OECD Taxation Working Papers, No. 12, OECD Publishing.