Public debt peaked in 2014 and, ever since, it has been falling, albeit very gradually. To put it in perspective, if the volume of liabilities skyrocketed from 35.6 percent of GDP at the end of 2007 to 100.4 percent at the end of 2014 (64.5 points more), in the last three years, it has been cut by 2.1 points, to stand at 98.3 percent of GDP in fiscal year 2017. This decline has been driven by strong GDP growth —over 3 percent in each of these three years— and an increase in prices, which started off being very moderate but growing more and more vigorous. In addition, the containment of the burden of interest has helped a lot. By contrast, the still significant public deficit has weighed the adjustment, frustrating the decrease in debt in those years.

If Spain had maintained a policy of zero deficit between 2015 and 2017, the debt would have fallen by 10.9 basis points, thanks to the growth factor alone. That is, five times more than it did. Even if the Government had incurred a deficit of 2 percent of GDP in each of these years, the adjustment would have amounted to 5.1 points of GDP. However, for the future, it is expected that growth will lose dynamism. On the one hand, a large part of the increase in GDP has been due to a strong rebound in employment, but this advance is beginning to slow down, and it will do so even more with the decrease in unemployment, as, although there is a large number of jobless people able to find a job with increased activity, many others have their capabilities very obsolete. It should be remembered that 1.5 million people have been unemployed for more than two years, and two thirds of all the unemployed lack training beyond primary and secondary education.

In addition, the low unemployment levels that will be registered in a few years will begin to push up wages, making it difficult to create jobs and, perhaps, domestic demand. It is possible that this increase in labour costs will even decrease exports in the medium and long-term. And all this can contribute to worsening the betterment of the Spanish GDP.

On the other hand, growth in recent years has been sustained on a non-satisfied demand for durable consumer goods, equipment and housing, that is, purchases pending for years that did not come to be executed due to the lack of confidence in the economy. Retained demand for consumer goods was released between 2014 and 2017, but it is already sold out, which diminishes the potential for growth. However, we are yet to see how long demand for equipment and housing lasts, and to what extent these increases endure over time.

For the next few decades, we must also consider the demographic projection of the country, which is very negative. If in 2018 there are 29.2 million people of working age —between 18 and 64 years old—, by 2028, this figure will have been reduced by 1.2 million people, down to 28 million, and by 2048, by 5, 4 million more people —22.6 million. This means that, even in a full employment scenario and later retirement, the demographic factor will be detrimental for GDP growth. And, finally, although there may be an impulse through immigration, the positive impact that has occurred in the las decades due to women entering the labour force will cease to be as prominent. Therefore, in the medium term, economic growth will be very limited, and will depend almost exclusively on advances in productivity. Although the nominal GDP growth will increase due to the normalization of the price rises, everything points out that it will still gradually diminishing. The International Monetary Fund even points to at a slowdown in real GDP below 2 percent in the next decade.

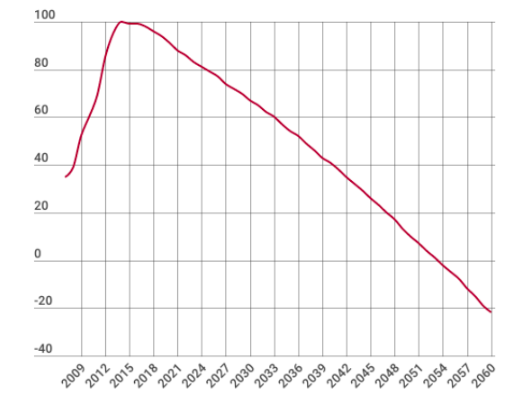

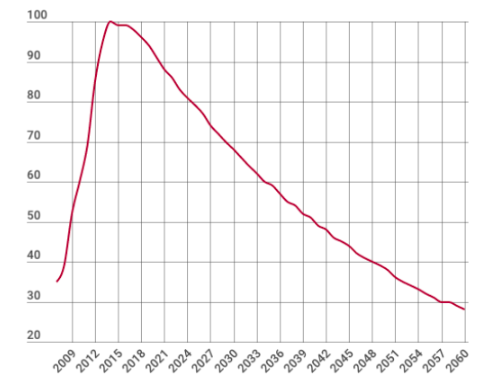

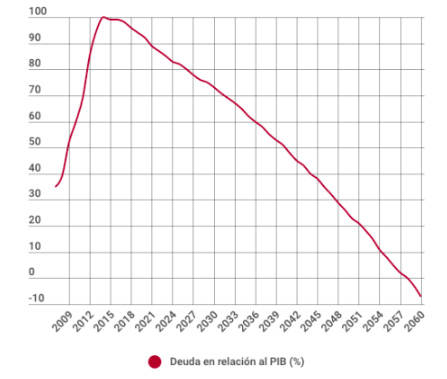

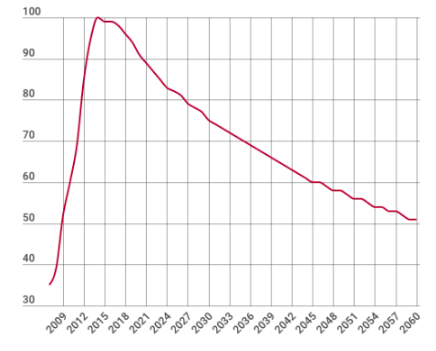

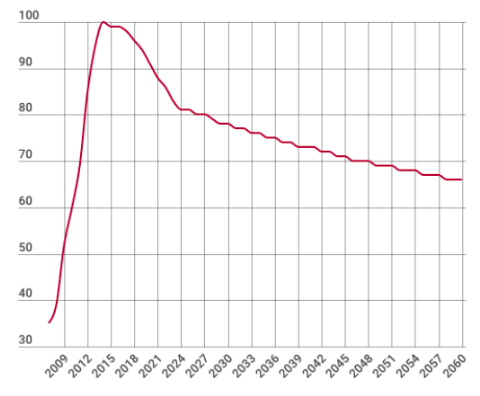

Thus, public debt would not fall below 60 percent of GDP —the figure marked as a reliable reference by the European Commission— until 2034, and it would not reach the levels prior to the bursting of the housing bubble until 2042. This scenario stems from the assumption that nominal GDP growth remains relatively stable, albeit with a gradual deceleration to 3 percent, while spending is controlled at 39.3 percent of GDP, as expected by the Government in the medium term, while revenues increase 10 percent above nominal GDP — the average of the past years. Furthermore, in order to be fulfilled, budgetary containment measures would have to continue even after reaching a surplus. If this were not the case, and only budgetary balance was reached —as it is very likely to happen if the difficulties to approve the Budget persist—, Spain would not be back to the levels of public debt prior to the crisis until 2052: 45 years after the outbreak of the crisis.

Graph 1. Evolution of the debt with surplus (Debt-to-GDP ratio)

Graph 2. Evolution of the debt with budget balance (Debt-to-GDP ratio)

Therefore, this scenario is subject to multiple constraints, and presents enormous vulnerabilities. What would happen if a new recession is unleashed in the coming years? What if interest rates rise? What if Spain suffers a prolonged period of low growth and low inflation? What if the government is unable to control spending for a while? What if several of these situations take place simultaneously? The possibility that they occur is very likely, and any of these would completely derail the process of debt reduction.

Recession scenario

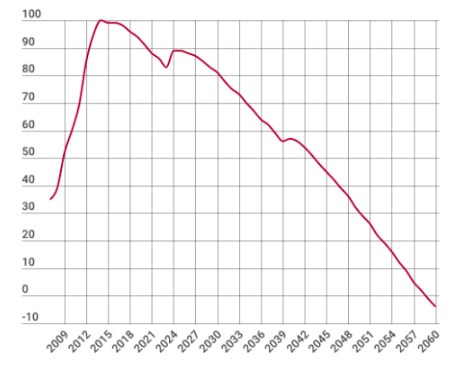

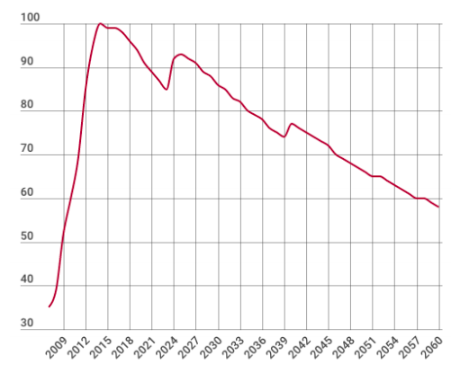

Historically, recessions have proven to be unavoidable. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, economic cycles in the EU have lasted about eleven years, although they have a tendency to continue. The last, which started in 1994, lasted almost fifteen years. According to this calculation, the next crisis would have to explode around 2023, and by 2038 there would be a new one. Obviously, these cycles depend on human behavior, so we can not assure when the next recession will occur, although it may be very likely that, by 2050, at least two major setbacks in the economy will have been triggered. They tend to last, on average, four quarters.

With this perspective —two recessions in the next 32 years and GDP decreases of 3 percent per annum in each of these periods—, the debt would remain above 60 percent of GDP until 2037, and it would not fall to pre-crisis levels until 2047. The ability to react to these depressions depends on what has been saved during the expansive periods. Therefore, a plan is urgently needed to quickly achieve a surplus and accelerate debt reduction, in order to build a cushion of assets with which to settle, or at least mitigate, the next recession. A level of debt around 40 percent of GDP would allow some maneuvering capacity before crisis, either by lowering taxes or maintaining an increase in essential expenses above the GDP trend. However, serious crises have not been taken into account, such as the one that occurred after 2007, in which not only did the economy as a whole collapsed, but the entire financial system was also at risk. In addition, unemployment tripled, and funds collection derived from the sale of real estate sank completely, all of which resulted in a deficit of more than 11 percent of GDP. If this happens again with a debt level as today’s, the consequences seem unprecedented.

If the first of the expected recessions were deeper and prolonged —with a deterioration of 4.5 percent one year, and 3 percent the next—, the forecast would be much worse, due to the inability to apply countercyclical measures and because the increase of the costs of the debt would consume part of the budget necessary to react. This way, the country would not enter surplus until 2030, and the reference level of 60 percent would not be reached until 2038.

There are two issues that perfectly show that Spain is not in a position to face a new deep crisis. The first is the structural deficit —when the effects of the cycle are canceled—, which is still the highest in the EU, at 2.6 percent of GDP. This is because Spain has used the years of growth to cut taxes and maintain some expansion of public spending, instead of making the most of the situation to reduce the deficit. Although this policy has served to increase growth, continuing with this trend will make it more difficult to respond appropriately during the next recession. The second issue is the level of public debt throughout the economic cycle. Spain is in the same position —incipient recovery— as it was in 1998. However, the current debt levels are practically stagnant at 100 percent of GDP, while in 1998 such level was at 62.5 percent and showed a a downward pattern, with falls in relation to GDP that doubled those that have taken place in Spain in recent years. Therefore, it very unlikely that, when the next recession comes, Spain is better prepared than in 2007, in terms of debt. In fact, at that time, our country enjoyed a primary surplus —before interest— of 2 percent of GDP, while now it is in primary budget balance.

Graph 3. Scenario of double recession (Debt-to-GDP ratio)

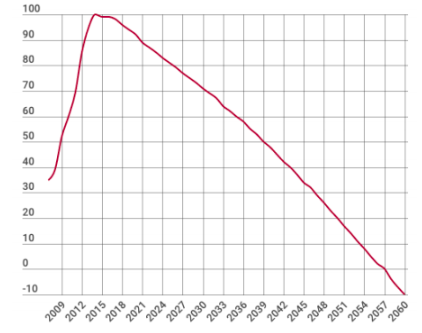

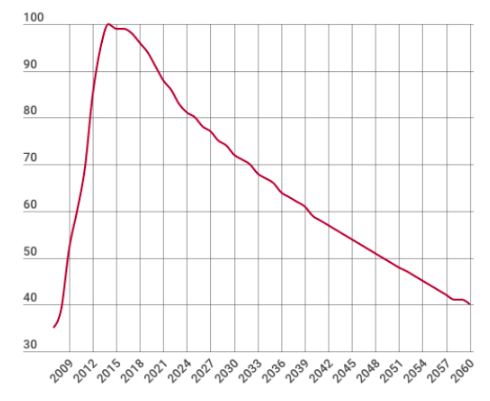

Scenario of interest rate increases

A second possibility is the rise in interest rates, which are now at historic lows. The European Central Bank (ECB) has already begun to contract its asset purchase plans and, at some point, it will have to start reducing its balance sheet and raising interest rates. As this process takes place, it is foreseeable that the interest rates of the debt will increase again. This affects the sustainability of the debt, since, up until now, the public spending adjustments have been produced by the reduction of financial costs, a dynamic that could be reversed shortly. Unlike in the 2010-2013 stage, the financial costs do not have to increase substantially in the first steps of the rise in interest rates, due to the progressive extension of the maturity dates of the bonds since the total amount of debt in relation to GDP seems controlled. However, given the fact that it is very high and it will remain so for the next decades, the long-term risk is much greater, despite the development of new mechanisms in the Eurozone. Therefore, the rise in interest rates can cause a strong increase in financial expenses in the medium term.

Currently, the average interest rate of public debt in circulation is 2.5 percent, an exceptionally low figure, so that normalization could significantly increase financial costs. Let’s take two references: the average of the last 17 years (3.8 percent), and that of the fiscal years prior to the crisis (4.5 percent). If the debt rates were to return to these values, over a period of ten years, the financial costs would increase by 16,400 million euros and 23,700 million euros, respectively. This would hinder the decline in debt, even in the case that half of these extra expenses are absorbed by the decrease of other items. In this case, the higher interest on the debt would delay the entry into a balanced budget situation, which could not take place until 2033. The greater volume of debt accumulated in those years would imply new financial costs, and this situation would cause the GDP-to-debt ratio not to fall below 60 percent until 2037, assuming that the average interest rate stood at 4.5 percent.

Graph 4. Evolution of the debt with an interest rate of 3.8 percent (Debt in relation to GDP)

Graph 5. Evolution of the debt with an interest rate of 4.5 percent (Debt-to-GDP ratio)

Uncontrolled spending scenario

One of the main fears of rating agencies is that public expenditures are once again out of control, something that may have multiple causes: from a Parliament that is more and more divided, that requires more assignments to approve the general budget, up to the increases associated with the progressive aging of the population. The European Commission estimates that, over the next three decades, this amount, due to the rise in spending on pensions, and the higher health care costs due to longevity or care for the elderly, could rise between two and three GDP points. If Spain did not manage to balance its accounts in this scenario, but maintained a deficit of around 1 percent of annual GDP, the debt would not fall below 60 percent of GDP until 2047. Under these circumstances, over the next 30 years, Spain would still be very vulnerable to a new crisis that could put the public finances on the ropes again. In that case, it is quite possible that the public debt will go up again in a few years, ruining any attempt to maintain a welfare state in which expenses are nearly matched to incomes.

Graph 6. Evolution of the debt with regular growth (Debt-to-GDP ratio)

A variant of this situation is that Spain enters recession in a timely manner on two occasions over the next three decades, as anticipated in the first of the scenarios. In this case, in addition, the absence of a fiscal cushion would make overcoming any crisis harder, given that it would be more complicated to apply countercyclical policies and new rises could be seen in the risk premium that would force to derive resources to the payment of debt. In this case, the volume of this would not fall below the target set by the European Commission for 40 years, in 2058.

Graph 7. Evolution of the debt with two recessions (Debt-to-GDP ratio)

Logically, the possibility that in this period there is an event that ruins the downward trajectory of the debt is very high. Therefore, as the debt adjustment scenario moves away to 60 percent of GDP, the probability of deviating from this path also increase.

Low growth scenario

Finally, there is a possibility that the growth of the Spanish economy will slow down from 2025, with an annual growth of nominal GDP of 2 percent. This may be because, as of that date, the number of retirements is much higher than the number of new entrants to the labour market, unless immigration changes this trend. This, together with a hypothetical moderation in productivity and prices, can weigh on growth over the next few years. However, this perspective, within a budget balance situation, would not be as worrisome as the previous scenario from the point of view of the debt, since it would allow to adjust debt below 60 percent of GDP in the year 2040.

Graph 8. Evolution of debt with zero deficit

However, this is not the most likely situation, as a low-growth scenario will also grip the increase in revenue, leading to a budget gap. Again, with a deficit of 1 percent of GDP and slow growth, the debt would not fall below 60 percent of GDP until after 2060.

Graph 9. Evolution of the debt with a deficit of 1 percent of GDP

Need for a fiscal mattress

The first conclusion of this report, taken all the scenarios described as a whole, is clear: Spain is subject to a huge risk. Despite the Eurozone’s umbrella, debt reduction is threatened by probable recessions and insoslayables challenges —increased longevity expenses. These weaknesses can trigger the risk premium once again, complicating the maintenance of the budget balance. Therefore, we must accelerate the country’s entry into a surplus state, and maintain a strong positive balance over the next decade. The coming years will be crucial for the adjustment of the volume of debt, since growth will still play a favorable role in reducing the size of liabilities. In addition, despite the fact that the deficit remains high, expenditures seem easier to adjust now than later on, due to the growing demographic aging. On the other hand, reducing the interest burden is an extra help to keep the budget under control, something that may be reversed in the medium term.

Similarly, the decrease in unemployment costs will also lose strength in the future. The second reason why it is necessary to generate a fiscal cushion is that it is not known when the next recession will come, but the best way to deal with it will be to have a budgetary room for maneuver, which would allow to reduce taxes or finance some type of countercyclical policies. In addition, a lower level of debt minimizes the pernicious effects of a rise in interest rates due to the entry into recession, which helps to avoid a vicious cycle like the one that took place between 2010 and 2013. In those years, the rise in financial costs made it difficult to adjust the deficit, and the risk of it becoming more high raised interest rates. The evolution of the situation in half of the scenarios contemplated makes it likely that the debt will not be reduced below 80 percent of GDP until at least 2027, which will prevent it from reacting effectively to a new crisis. If it were the case that the debt continued to be high and the fall in growth, deep, a tax increase, however necessary to clear up doubts about the solvency of the State, would only intensify the depression.

In addition, an element that could hinder the long-term sustainability of the debt is the budgetary assignments of the People’s Party to the PNV (Basque Nationalist Party) in matters of pensions. If the new taxes are insufficient to compensate for the cost overrun of Social Security costs, these will not only make it difficult to reduce the deficit in the cost term, but will make it more likely that Spain will fall into the scenario of uncontrolled expenses described previously. We must keep in mind that the cost of pensions is one of the most difficult to correct in the short term, and doing so implies a very high electoral cost. In addition, the reversal of the 2013 reform makes a new postponement more feasible in the future. The increase in pensions projected for 2018 and 2019 will not only have a strong extra cost the first year, but will move into the future, since the higher payrolls of these two years will serve as the basis for subsequent ones. At the same time, the delay in the introduction of the Sustainability Factor will have a strong effect in the long term, since it will end up raising the cost of the pension system by about 2 percent. And this can be critical when, according to AIReF (an independent tax-specialized think tank), the cost of pensions will exceed 300,000 million euros a year by 2044. Therefore, these measures can raise the debt by about five points of our GDP in the long term. It should also be considered that the cost of financing this added deficit will entail a higher cost in interest on the debt, which could have a long-term impact of 1.8 GDP points. All this will delay between three and four years the entry into a debt situation below 60 percent, according to the average evolution in the set of scenarios.