CHAPTER I. THE DATA MARKET

We live in a period of exciting innovations and changes. The World Economic Forum calls it the worldwide website since communication, new technologies and the internet connect people in one single network [1]. The accessibility to information has increased considerably, especially thanks to the appearance of new intermediaries, and the transaction has been facilitated across national borders, both for individuals and companies. This new world, characterised by deep interconnectedness, has seen the development of a true digital economy emerge with its own rules, winners and losers. Among the latter we find companies that could not, or have not wanted to transform their business model in accordance with the changes of the technological revolution; among the winners are the so-called ‘digital platforms.’ This expression refers to companies whose business model allows multiple participants to connect, interact with each other, and exchange value. The European Commission defines them as «all those companies that cover different types of activities such as online marketplaces, social media, application distribution platforms, price comparison websites, and platforms for economic collaboration, as well as online search engines» [2]. It is also important to consider that certain digital platforms have been gaining more power in their markets and, therefore, more attention from the authorities in the public debate. Therefore, even though they present many similar characteristics, this report focuses on just a few: those that have managed to gain more market share and are having a greater impact, whether in benefits or societal risks (chapter 2).

As we will see over the course of this study, the core of the business model of these new companies consists of the collection and management of ‘data,’ a term that encompasses the set of information from the users of these platforms: who we are, our interests, our past and, probably, speculations about our near future. This immense flow of data has created new infrastructures, new businesses and, fundamentally, new economies, as well as new challenges for society. This revolution promises to bring about a radical change, which we are already witnessing in many industries such as health and finance [3]. For these reasons, it is of paramount importance to understand how this market works and the importance of data in order for a company to remain competitive.

This introduction will consequently present some fundamental characteristics of digital platforms, which explain both their general operation and the origins of their recent success. At the same time, this will allow for better understanding of the most relevant problems (Chapters 2 and 3).

To carry out this semblance, one must consider the company’s data market mechanism, which is the basis of the business model adopted by the companies that the study will cover. Once this element has been investigated, the three dimensions of digital economy success will be addressed. They are increasing returns to scale, the network effect, and the virtuous cycle of data.

The data market

As previously mentioned, personal data implies any type of information that an or company leaves online: his movements, interests, relationships and details that, more or less consciously, are entered on the internet. Thus, a user’s data is essentially one’s digital record showing his or her evolution on the web. Within this registry, the data evolves based on the information provided through digital platforms, and is stored in some base that pertains to the user’s digital identity. However, not all of this data is provided by the user. The World Economic Forum categorises the data according to its form of acquisition into three groups: volunteered, observed and inferred. Volunteered data is that which the person gives directly to the platform in exchange for receiving a service. For example, bank data in an online transaction or personal data when one subscribes to an online platform. The observed data is acquired from the history of movements that an individual makes within an online platform. For example, purchases, or preferences that are set to receive more services: the platform observes and acquires these preferences in order to offer similar benefits in the future. Finally, the inferred data is not provided by individuals, but obtained through an analysis of voluntary and historical data. This data allows a company to be more competitive than others, because it can draw advantageous conclusions for its business through costumer analysis. For example, analysing voluntary and observed data provides the opportunity to discover other interests that are not specifically stated. Each type of this personal data (voluntary, observed or inferred) can be created by multiple sources (devices, software, applications), stored and aggregated by various providers (web, internet, search engine, or utility retailers) and evaluated for a wide variety of purposes and very different users (end users, companies, public organisations) [4]. Therefore, the delimitation between the different types of data is not always clear.

This systematisation opens the door to further consideration of data ownership and accessibility. Although data is mostly provided by users (e.g. via social media posts, emails, and instant messages), the answer to the question of who owns the data and how accessible it truly is less obvious. After Europe’s approval of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which we will break down in more detail in Chapter 4, data requests are a possibility for European citizens today, but the process of obtaining it does not excel for its speed and simplicity [5]. The fact that digital platforms retain the data of their users, unless explicitly requested otherwise, does not take into account that, from their easy accumulation other Internet users could increase their knowledge of anyone, and underestimates the risk of information leakage in case the data is hacked or simply sold. On the other hand, as we will see throughout the report, digital platforms feed on the availability of data to improve their market position and even reach a monopoly (in particular, through the ‘network effect’ that will be described later). Overcoming this risk, and ensuring that the benefits of competition continue to exist throughout the sector, implies rethinking the concept of data property rights by applying reforms similar to those in other sectors such as the mobile telephone sector. In fact, in this last field, most countries have established the right to ‘portability,’ where the telephone number belongs to the user and not to the company that supplies it, which promotes competition between companies and reduces consumer prices. In the same way, several authors are postulating the hypothesis that users have their own network of digital relationships (‘social graph’) that they have created in a social network, and can transfer this data to a new platform without losing his network of ‘friends’ [6].

Another important characteristic of the data market is the different ways in which it can be used. The European Commission defines four categories of use: non-anonymous use of individual data, anonymous use of individual data, aggregated data and contextual data [7]:

- By the non-anonymous use of individual data, it refers to what is given to offer a service to an individual. For example, a company that sells products online uses them to better combine people’s preferences with new or different products that might interest them.

- The anonymous use of individual data is useful when trying to improve a machine learning program [8].

- The aggregated data is used at the group level, such as that provided by public institutions about the population of a country.

- Contextual data are those external to individuals that are used to offer them a better service: location, temperature, places, etc.

The different types of data and categories of use are necessary aspects of the debate on protection and privacy, because they explain the complexity of this market. Other characteristics of the digital economy clarify why these new competitive models are not always compatible with traditional ones. Many of the innovative digital markets derived from the internet, such as search engines, social networks or e-commerce, suffer from a high concentration, which allows them to be dominated by one or a few companies. In the following pages, we will describe the main reasons why these markets are different and, therefore, need new proposals:

- Digital platforms have achieved, thanks to different types of data, returns to scale that are increasing. This means, on the one hand, that the marginal cost decreases as the number of users increases and, on the other, that acquiring a new data is always positive for the digital platform.

- The effects of network (network effects): The convenience of using a technology or service increases with the number of consumers who adopt it. Consequently, it is not enough for a new participant to offer a better quality and/or a lower price than the ‘incumbent’ company; the startup will also have to convince the owner’s users to coordinate a migration to its own services.

- The Artificial Intelligence (AI) cycle: With the advances in new technologies, companies can use data exponentially, creating a virtuous circle within their business models.

- Returns to Scale

The digital economy is first and foremost an information market. Digital platforms and all companies that focus their business model on data basically sell it to improve a service or launch new products. However, economic theory considers information as a public good that is non-rivalrous and non-exclusive [9]. This means that it cannot be sold as such, since offering it to another individual or company does not exclude its continued use. Along with this definition, the current revenue that digital companies make from data collection shows how the possession of information can only have positive effects for a company and implies increasing returns to scale. Because of this, although the initial cost of obtaining data is high, once an additional user is served, the costs do not increase proportionally. In fact, once a digital asset has been created, its cost of transmission to other individuals is practically nil.

Regarding this point, there are two questions that serve as an example to understand the strength of increasing returns to scale within the digital platforms business model. According to Facebook data as of March 31, 2019, this social network has around 65,000 monthly users for each worker [10]. However this company can only afford to spend around 1% of its annual value to pay its employees, because they get the rest of their work ‘free’ from users. In contrast, a company with a more traditional business model like Walmart allocates 40% of its value to wages [11]. Furthermore, increasing returns to scale creates barriers to entry and thus constitutes a constraint on competition. Thus, digital platforms, thanks to a high number of clients and a low average cost, are able to offer products at a low price and of good quality; prices that a new company cannot match without undertaking the same large-scale operation to pay fixed costs. A start-up interested in providing a new service will only achieve a large scale if the quality is high. Therefore, a potential participant will not enter the market to challenge the dominant company.

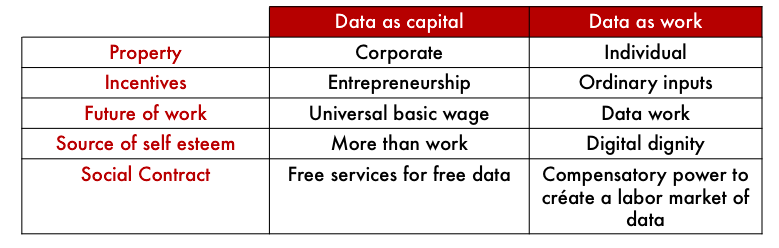

The presence of large economies of scale also helps to understand the increase in free services. Digital platforms have managed to distribute ‘free’ services in exchange for data, since their highest income comes from advertising. This coincidence of new needs and lack of knowledge on the part of the user about new technologies have created a type of barter economy between platform and consumer in which data is exchanged for services. Therefore, data has become a product that in turn becomes capital for companies, which use it as if it were their own. In this report, we study a possible alternative to this use of data by digital platforms that would create a more efficient business model.

2. Network Effect

The second aspect that differentiates this market from a classic model is the ‘network effect;’ that is, the convenience of using a platform is directly related to the number of users that are on it. For example, consider Facebook or LinkedIn: their success lies it the large number of individuals are connected through the same network. As we will see in the following chapters, this effect has a double impact for the ‘incumbent’: on the one hand, it is positive because it raises the barrier of entry to potential competitors. On the other hand, once a company manages to enter the market and capture many customers, the company that has preceded it can become completely obsolete (i.e. MySpace, or MSN). For this reason, markets with network effects are prone to concentration: consumers benefit from being on the same network as other users. No one wants to be alone on their own social network.

An interesting case within the network effect is that of multi-sided platforms, also known as matchmakers, which bring together different groups with complementary interests, so that goods and services are exchanged. The clearest example is Airbnb, which connects apartment owners with tenants. It is worth noting that this type of business has been used often in recent years in the world of fintechs to enter different industries and completely break their business models. Consider the payment system, loans between individuals (P2P Lending), or crowdfunding. For each of these sectors, digital platforms have managed to unite consumers with bidders, leaving the intermediary aside.

Along these lines, the platforms find an advantage in not charging users to enter their system, since they know that the data they provide will serve to impute a higher price to advertising companies and to attract more customers. Thus, Gmail users pay a monetary price of zero, but allow Google to read their emails so that advertisers can market them based on their personal information. Google, on the other hand, can charge a high price for ads. [12] As in the case of returns to scale, network effects also make it very difficult for a new company to enter a market where there is already a platform. The reason for this is the difficulty of moving many users en masse to the new platform, and the lack of incentives at the individual level to move away from one which holds more interest. In this way, network effects could prevent a new platform from replacing an old one. Even though they cannot be avoided, these ‘effects’ make the transition slower and more costly for the new market leader than they would be otherwise [13]. The high barriers to entry due to the network effect leads us to believe that the market may be more efficient when there is a monopoly. Based on this assumption, which we will discuss throughout the report and offer a counter-proposition rooted in free competition, some authors suggest that the best way to limit these monopolies is through a policy of regulation, instead of create a more competitive market open to other companies [14].

This issue is especially important as the interest of the platforms diverges from the public interest. Large social platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are occupying an increasingly prominent position as intermediaries in the debate and in the formation of cultural norms [15]. This has relevant side effects in the social sphere even beyond the realm of platforms. Therefore, there is no reason to expect them to manage the situation efficiently: they have an incentive to abuse their dominant role, thereby increasing their political influence [16].

3. The Virtuous Cycle of Data

A final aspect worth noting is how the evolution of technology has been affecting the data market. The idea that information on users is the central asset for digital giants became increasingly true with the explosion of big data, machine learning and artificial intelligence in business models of companies and in aspects of our daily life [17]. In fact, as the European Commission report suggests, data is one of the key ingredients in artificial intelligence (AI), and a crucial input to production, logistics and targeted marketing processes. The ability to use data in innovative developments is a competitive advantage whose importance will continue to increase [18]. In many ways, investing in big data has moved towards artificial intelligence, making it the driving force behind both data collection from many organisations and efforts to monetize it under the premise of offering better services and products to users. At the heart of AI implementation is one of the machine learning techniques called supervised learning, which uses data to form an A to B relationship. For example, a system determines whether an email is spam or not, or the objects in an image. In other words, it assimilates data and generates a result. This information can be presented in structured (spreadsheet) or unstructured formats, such as audio, video and text. The more data available, the more powerful the algorithms will be; the technology that has allowed AI to grow exponentially in recent years is development of neural networks [19]. In traditional machine learning models, even if the volume of the data grew, the possibilities of AI were limited. Now, thanks to these neural networks, the barrier has been broken and the performance of the AI only depends on two aspects: the amount of data and computational power. Thus, if more data is processed in better neural networks, the evolution of AI will continue to improve. In the book Radical Market, the authors offer an in-depth explanation of the operation of these neural networks. Instead of the inputs determining directly and independently of the outputs, neural networks combine inputs in complex ways to create ‘characteristics’ of the phenomenon being studied, which in turn conditions others, in order to reach different results [20]. This brings us to the last point of the current strength of the data markets: the virtuous cycle of AI.

This beings in a company which, through the creation of a product, attracts users who will offer more data. The acquisition of this information by the company, together with the integration of AI technologies, will allow companies to create a perfect product for the consumer by means of a feedback loop where the product continuously improves with use, thereby improving its competitive stance. This virtuous circuit, together with neural networks, has led digital platforms to play an increasingly important role in the market and invest more capital to get more information from users. Thus, the vast data sets collected by Google, Facebook, and others as a by-product of their core business functions have become a crucial source of revenue and competitive advantage. Companies that started as free service providers and transformed into advertising platforms are now in the process of becoming data collectors, through services that attract users and encourage them to provide information with which they develop AI through machine learning.

Delving into these characteristics allows us to identify the main component of the companies’ business models that are active in the digital economy. Throughout this report, we will try to detail the challenges that our society must face while balancing the benefits obtained with related threats (Chapter 2). In particular, we will focus on the topic of privacy and data protection (Chapters 3 and 4), which are playing an increasingly important role in the debate over digital platforms. At the heart of the problem lies a simple consideration: the business model of these companies is based on an ongoing incentive to capture an increasing number of information about their users, and to be as competitive as possible. The need to access new data and the ease with which it is obtained often leads to the question of whether privacy even still exists in the debate [21]. Regarding this vision of an ‘end of privacy,’ which was later partially retracted by its own author [22], we will see later on how it is more accurate to speak of a ‘privacy paradox,’ according to which more and more users are concerned about their privacy, but at the same time share more personal information.

Addressing this problem in respect to privacy, which is understood as a universal human right (article 12), aligns with data protection, constituting a challenge that affects our society in an interdisciplinary manner. During this debate, we will observe that behind the proposed solutions often hide various philosophical conceptions. Our view in this regard will take the empirical data, where available, as a starting point. This data will be compared to the intellectual heritage of the classical liberal tradition, which has made the defense of privacy a cornerstone. In this sense, it will be interesting to observe how, even if the respect for the right to privacy is historically opposed to state control, the current concern is rather about its protection against violation by companies. By delving into this topic, we will consider what kind of regulatory solutions are being implemented (Chapter 4), especially in the European sphere, to affirm this right.

Finally, the regulation of privacy in the digital economy forms part of a more general approach to digital platforms; the solutions currently in vogue will be discussed in Chapter 5, and will be compared with the teachings of classical liberalism in Chapter 6.

CHAPTER II. THE BIG TECH

In the first chapter, we introduced the data market and analysed several characteristics related to its market structure that can lead to a lack of competition and a monopoly situation in different industries. In this chapter, we will explain the consequences of the data market for the business model of digital platforms and how it will develop in the future.

As we anticipated in the previous chapter, it is not easy to enclose the different types of platforms in a single definition. Therefore, from now on, we will define them as those technology companies whose line of business shares an open platform on which users exchange goods and services, and who sell their own [23]. This specific feature has led many politicians, academics and intellectuals to question the success of these platforms and to compare them with other industries or sectors that have become oligopolistic over time [24]. It is clear that any company that has the possibility of managing a platform and selling its products on it will end up making profits, which will increasingly increase its market power over other participants. The most successful such companies are the GAFAs: Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple (see BOX I). Each of them has managed to unite the two business lines just mentioned and create a dominant position within their platforms [25]. In this chapter, we will discuss two topics related to GAFAs. Firstly, some of the strategies they use to gain more power and offer better services (‘digital advertising’ and artificial intelligence) and secondly, the threats that these same companies generate for our society.

Digital Advertising

One of the aspects that yields the most returns for these platforms is ‘digital advertising,’ which is knowing how to target offers and products to users who may be interested. Facebook and Alphabet (Google’s holding company) obtain more than 90% of their income from digital advertising [26], and control more than 60% of this sector [27]. However, it is not limited to these two platforms. In recent years, Amazon and others have increased their advertising investment to improve their services and more easily reach potential customers. For example, Amazon can find out the last time a person has bought a certain product and what their favorite brand is. Advertisers are able to use this information to find the best targets and know when a potential customer will need a certain good [28], more efficiently and for less cost. Tae, for example, a sunglasses manufacturer: before digital advertising existed, this company needed to think about which magazines and television channels to advertise on to maximise consumer attraction. This strategy was very expensive and inefficient, because it did not control exactly which people saw that magazine or channel at the specific time the ad appeared. Today, thanks to digital advertising, both impacting the interested client and scheduling the advertisement is more precise. Continuing with our example, the sunglasses manufacturer will know if the person is looking for other sunglasses, summer clothes, or if they have gone out on a sunny day. All this information can be collected by digital platforms such as Amazon, Google and Facebook, provided to different companies, and thus facilitate their searches [29]. In turn, the advertising services offered by these platforms to companies increase the number of platform users (through the network effect) and learn best products and services of companies.

Before describing the consequences that digital advertising has had for the digital economy, it is important to go into greater detail of how this strategy works. Below, we explain different models related to digital advertising, using as a point of reference the two that have reported the most success: Google AdWords and Facebook Ads, the respective departments responsible for Google and Facebook advertising.

Google AdWords mainly follows a ‘pay-per-click’ (PPC) system. In other words, Google charges advertisers every time a user clicks on their advertising. The appearance of this through AdWords depends on two factors: first, that your search keywords match those that advertisers have associated their ad; second, on the company’s ‘Ad Rank’ with respect for its competitors. This ranking of companies is in turn subject to two elements: the price that advertisers are willing to pay for each click (following a bidding system) and the quality of the ads [30]. These two metrics multiply with each other, and the advertiser with the highest number will be the first paid ad to appear in search results. ‘The Quality Score’ depends on several parameters that allow advertisers to pay less:

- The Click-Through Rate (CTR) of the ad, or the percentage of clicks it generates with respect to the number of impressions, measured by the times that an ad is shown on the screen for the first time [31]. If the PPC ad has 1,000 impressions and 1 click, this equals a CTR of 0.1%. As a metric, the CTR indicates how relevant search engines are to finding the ad. Therefore, though a high CTR is generally better, one must take into account the efficiency of the ads. A low CTR is fine as long as keywords and ads perform correctly based on business goals.

- The relevance of the keywords that activate the ad with respect to the user’s search. For example, offering a free product in the ad just for users to enter the website will result in a low ‘quality score.’

- The quality of the web page, since the more relevant the landing page is to the ad, the greater the chances of obtaining a good ‘quality score.’

This system allows that the advertiser does not pay more to achieve greater visibility. The quality of the service and the user experience are fundamental elements for the advertising to obtain optimal results. In fact, the higher the quality, the lower the price that the advertiser pays [32].

Another method used by the platforms, apart from PPC, is the ‘Cost-per-mille’ (CPM), which denotes the price of 1,000 advertising impressions on a web page. Facebook ads have an average cost per click (CPC) of $ 1.86, and one per thousand visits (CPM) of $ 11.2, which varies depending on factors ranging from the quality of the ad to the competition. However, the true strength of Facebook’s immense audience lies in the detail with which advertisers can target users. Among the most used models in Facebook Ads is the ‘lookalike audience,’ a tool through which the platform finds potential clients based on past clients. For example, a book seller who knows his target audience may offer this database to Facebook, which in turn can help him find potential customers who share the same information. This type of advertising carries an important weight on a platform such as Facebook, where users share personal and private data with other members of their social network. Thus, this is the platform with the most information on interests and relationships. Of course, for advertising to bear fruit, it is important to have a high quality database. Although there may be a greater inclination to maximise the pool of possibilities, it should be borne in mind that smaller audiences often work better, since they are ultimately the ones that coincide the most with their source. Facebook recommends using an initial database of between 1,000 and 50,000 people to create similar audiences [33].

In conclusion, we can see how, through digital advertising, platforms have not only found a way to monetise their business, but also increase the amount of personal information of their users. The data industry defines target advertising as a ‘win-win-win’ situation, in which consumers, advertisers and platforms all gain something. It is a good for consumers, who see a reduction in the cost of searching for products; for advertisers, because they can find potential customers more easily; and for data intermediaries, or platforms, which capture money through these transactions [34]. Despite this, one problem that remains unsolved is that of consumer privacy: the true price to pay to benefit from this system. Furthermore, the ‘win-win-win’ situation proposed by the technology industry does not contemplate the lack of transparency in companies’ advertising on Facebook [35].

The second element that creates concern in public opinion is the use of AI advances by digital platforms to transform their businesses and enter new industries. Many of them have adopted machine learning and have integrated it into their corporate culture. As we saw in Chapter 1, for these companies AI is not just another tool, but the driving force behind their business model. This philosophy sets them apart from almost everyone else, including other tech giants, because they can analyse a digital data library and obtain valuable information about any industry they choose to penetrate [36]. Education [37], travel, healthcare [38] and many more are being completely revolutionised by digital platforms. In this report we will analyse one of the areas most affected by these companies and AI today: finance.

According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), in the last year financial services have accounted for almost 11% of Big Tech’s revenues [39]. Although much of this sector is concentrated in China and other developing countries, digital platforms are taking advantage of the high costs of the banking system in Europe and the United States to enter these markets as well. The World Economic Forum has analszed the financial areas most affected by new technologies: loans and deposits, insurance, payment systems, investments, the market for capital and market infrastructure [40]. We will study only the sectors that have emphasized digital platforms, which are payment and loan systems [41].

- Payment Services

This was the first service that Big Techs introduced in their business models to overcome the lack of trust between consumers and sellers [42], speed up the purchase of products on their platforms, and improve their use. In fact, the increase in AI has involved many changes in the payment system, such as a wider use of mobile interfaces which are faster than cash. It has also helped reduce fraud [43]. The main digital platforms have taken advantage of technological progress and the virtuous circle of data to offer their own payment systems. The simplest model is that of applications such as ApplePay and GooglePay, where users rely on third-party infrastructures (credit cards or retail payment systems) to process and settle payments. A more advanced model is embodied by AmazonGo, an ATM-free store that tracks what visitors have put in their cart and automatically charges for it using their preferred payment methods when they leave the store. Behind this system there is a notable effort in object recognition and machine learning [44]. The last digital platform worth mentioning is Facebook, which wants to go one step further by creating its own virtual currency, the Pound.

Its mission is very ambitious: to offer a payment service to all those who do not have a bank account, that is, approximately 1.7 million people [45]. The idea is to imitate the WeChat model in China [46], which has managed to unite different businesses in the same app and put itself at the center of people’s lives. The Pound model is made up of three parts that will work in coordination to generate a more inclusive financial system:

- It is based on a secure, scalable and reliable blockchain technology [47].

- It is backed by an asset reserve designed to give intrinsic value.

- It is ruled by the government of the independent Libra Association, whose mission lies in the evolution of the ecosystem [48].

So far, 28 companies, including payment companies, e-commerce groups, and venture capital firms, have disclosed that they will become sponsors and integrate this technology into their services [49]. The plan is to create a new Swiss-based non-profit foundation, made up of 100 members from the private sector and civil society with the same voting rights, to launch Libra in the first half of 2020 [50]. Libra holds the potential to take an entire generation to a more formal financial system that, in the long run, can help people build their credit and move up the socioeconomic ladder.

If, one side, it seems that the future of virtual currencies is coming closer as a more viable alternative to cash with which more people can enter the financial system, on the other side regulatory authorities and public institutions continue to state the risks that these currencies pose to the global financial system and to people’s privacy. On August 2, 2019, data protection authorities in the US, EU, UK, Australia and Canada released a joint statement expressing concern about Facebook’s plans and alerting that Libra «can instantly become the custodian of the personal information of millions of people» [51]. They also called for the creation of predetermined privacy protection settings and the use of so-called «dark patterns,” techniques that encourage people to share personal data with third parties [52]. The second area of concern centered around the global financial system. Libra would leave too much power in the hands of a self-selected group of large companies; it also would pose deeper systemic risks by interfering with the central banks’ ability to monitor their financial systems and operate monetary policy [53].

All of the models advanced by these platforms represent an advance for our society and, without a doubt, carry many advantages for businesses and individuals. However, through these new services, Big Techs can obtain more personal data and, therefore, greater power over our lives.

2. Loans and Deposit

The second market in which the platforms would have a great economic impact is that of loans. As the World Economic Forum reports, AI will be (is) a complete revolution. Loans will become smaller and more agile as they are customised for specific uses. The range of potential customers will increase as non-traditional data allows for serving new consumers and operating in new regions. Therefore, digital platforms have the advantage of personalising the type of loans in two ways: offering their own products, thanks to the personal data of their users, and creating a matchmaking platform for lenders and borrowers — both of which banks cannot do. In addition, with the new European rules of ‘Open Banking’ [54] and PSD2 [55], it will be easier for them to know the bank details of their users and, therefore, offer products to those who cannot afford a bank loan.

Amazon has opened a system of loans to small and medium-sized companies in the United Kingdom and the US; although the numbers do not equal those of e-commerce, this American giant is investing a lot of money in this sector and expects to grow in the coming years. Ebay, Amazon’s largest competitor, has also decided to enter this market through a collaboration with Banco Santander. The new company, Asto, will provide loans later this year [56] to more than 200,000 SMEs selling products through eBay in the UK. The main objective of the Spanish bank is to compete with the digital giants and the Fintech companies, using the same strategies: lots of user data and flexibility within the company when it comes to lowering costs.

The path of Big Techs in the loan market is still a long one, since the platforms do not yet own many bank details of their users. However, the collaboration between Ebay and Santander may set an example for banks and platforms to come together and grow in dimension and efficiency.

In this chapter, we have analysed different businesses that digital platforms have developed over time. Posner and Weyl at Radical Market speak of these as “companies that started out as free service providers looking for a revenue model and transformed into advertising platforms, and are now in the process of becoming data collectors, offering services that they attract users and encourage them to provide information on which they train artificial intelligence using machine learning ”[57]. Here we add one more aspect to this vital process of digital platforms: their ability to enter new markets thanks to the virtuous circles of AI and the enormous amount of data that they can process for free. In this post, we have presented only two of the markets that digital platforms are interested in. However, there are many more industries where they can enter and become leaders.

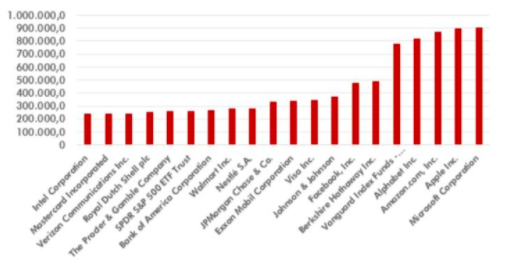

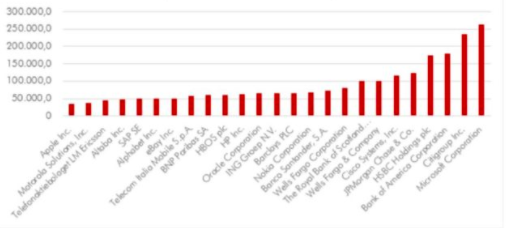

Many of these platforms have managed to establish themselves as the dominant companies in the market in just 15 years. As can be seen in Figure 1, the capitalisation of GAFAs is today among the largest in the world. All of them play a very important role in today’s society: they have been the most innovative in recent years, creating products and services with a global reach. For this reason, many governments and institutions have begun to discuss the risks that these platforms can pose as private companies in search of their own benefit. In this report we will briefly introduce different aspects that concern society, and then focus on the main point of our publication: privacy and the protection of personal data.

Graph 1. The 20 largest companies by capitalisation of the market on March 31, 2019 (millions of dollars)

The first danger worth treating which we have already mentioned several times is the monopoly that these companies bring to their respective industries. In recent years, politicians and academics have debated the possible existence of a concentration of power in digital platforms and how it can affect competition, innovation and market structure. The case of Google serves as an example this dynamic.

Another danger related to digital platforms and their market structure concerns democracy and its effects on politics. The Cambridge Analytica case (see BOX II) reveals the pernicious consequences that these platforms can cause in a democratic society.

Finally, privacy: in recent times, it has become increasingly common to find news about a scandal related to privacy, whether it is the breakdown of the security cables that defend confidential personal information, or the revision of privacy policies by digital platforms that do not fulfill previous promises to defend their users.

This type of news, when disseminated by the media, generates a general feeling of panic, which results in the desire to withdraw from the platform that is the subject of the controversy. At best, it arouses growing distrust of the system; a very important cost in an interconnected society like ours, which opens the debate on how to solve the problem. A solution requires balancing the incentive of companies to collect an increasing amount of user data, in order to offer more personalised services and gain market share, while maintaining the right to privacy that today encompasses even the protection of user data. Therefore, solutions must be found that overcome the dichotomy between market forces alone and regulation alone. The first option, as we will see, presents the danger of ineffectiveness in achieving an optimal result. The second is to place a the burden on small and medium-sized companies operating in the digital platform sector with a compliance that is difficult to bear and, therefore, would indirectly translate into an advantage for incumbent companies and their growing monopoly position.

The problem of privacy manipulation is of paramount importance, not only because it has consequences in our most important institutions (see BOX II in Cambridge Analytica), but because it threatens to undermine a fundamental pillar of society: that of trust.

CHAPTER III. PRIVACY

Can privacy exist in the digital age? In a hyperconnected world, where people interact daily through some digital platform, is it possible to talk about a right to privacy? The very fact that this question is asked underscores the profound transformation regarding the cultural context in which the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was elaborated. Article 12 establishes the following:

“No person may be the object of arbitrary interference in his/her private life, in his/her family, in his/her house, in his/her correspondence, or damage his/her honor and reputation. Everyone has the right to be protected by law against such interference or injury. ”

These words intended to reaffirm the right of every person to maintain control over their information: a prerequisite for the exercise of other freedoms. On account of this clause, the State or any other power had to refrain from arbitrarily or illegally interfering in people’s lives. From this text it is possible to understand that privacy is a difficult right to respect, because it refers to a particularly intimate sphere of the person and because it has to confront technology and an increasing need for security, both at the national and international levels.

The technological development that we have witnessed in recent decades has required a new elaboration of the right to privacy, which has gradually been extended to the type of access to personal information that we share when using digital services, the protection of data contained in it, and the control that users have of their data.

The differing attitudes of consumers towards online privacy makes this difficult situation even more complex: they are divided between those who consider confidentiality something more or less indispensable, and those who are willing to give it up in return for services; this reality cannot be ignored when designing the regulation, discouraging one single solution. The inability to collect this diversity of user opinion in a single proposal has been a source of enormous interest for digital platforms, which have reaped considerable benefits precisely by playing with the cultural change of consumers.

The Facebook case

One paradigmatic case is provided by Facebook. Since its founding in 2003, this popular platform has shifted its stance on the importance of respect for privacy, with reforms aimed at achieving a greater dissemination of information [58].

At the time of this social network’s launch, privacy was of such importance that Facebook created a line of special attention on the subject. Consumers showed appreciation for this approach by choosing this platform over other competitors. Given the existence of other free social networks such as MySpace, Facebook realised the need for a competitive advantage to differentiate itself, and they did so in response to concerns about privacy [59].

This strategy led the company to restrict access to those users who could validate their identity with an email address established by a university (“.edu”), and the default settings were designed so that subscribers could only see the profiles of university colleagues. MySpace had more open default options, and all users could see each other’s accounts [60]. This may seem to be a simple detail at first glance, but contributed to the quality of the product because, as extensive scientific research shows, consumers are reluctant to change the default configuration so the company’s settings become definitive for many users [61]. An additional commitment to privacy compliance was that Facebook would not use a technology such as cookies. These — short codes that digital platforms can install on computers through the URLs of their web pages — allow a site to remember a user’s actions (buy a product, log in to a site) accessed through a browser, in order to improve the quality of the web page experience. By additionally determining what the user is looking for, reading, or buying, these cookies constitute a kind of fingerprint that the Internet user leaves on the visited web page, and that the company that owns the site can use to track the details (location geographic, visit time, IP address, cookie ID) of that visit. Two characteristics limit the use of cookies by companies. The first, that a company can only read its own cookies; the second, that they will only be able to read them when the user initiates a search on the website’s server (the information they can obtain about the user relates to what is on their website and not to others) [62].

It might be possible for a company to circumvent these privacy protections by installing its own code on another company’s website, but the latter would never allow this (a simple demonstration of how competition between companies translates into better privacy for the user). The situation changes when a platform such as Facebook becomes an intermediary in online browsing (for example, through searches on websites initiated through the Facebook account). This generates some complications for data protection. Firstly, Facebook associates a certain cookie ID with the user’s identity, so the website search will no longer correspond to an anonymous code, linked to the user’s computer, but to the specific social media account. The second complication is that, in this way, Facebook can collect much more comprehensive information about the tastes and preferences of users [63]. To alleviate the concern raised, Facebook initially assured that it did not control the behavior of users outside the platform, and also that it gave users the option to refuse any disclosure of their own information to third parties, as well as prohibit Facebook from collecting information about them from third parties. Facebook’s presentation as a ‘closed’ social network with strict pre-determined privacy options earned high consumer preference, which gave Facebook a position that, as of 2014, could be considered a monopoly according to several sources cited in this report. Once Facebook gained this control, it soon began to review its privacy policies — especially those related to user surveillance for commercial purposes, using a technological scheme built over the years under the assurance that it would specifically not be used it for this purpose. Therefore, this position of strong dominance in the market was built on promises that were subsequently modified for the company’s benefit. These changes to privacy have not gone unnoticed. The Cambridge Analytica scandal (see BOX II) was most notable, leading to further investigation on the subject.

Anonymity and control

The Facebook case might suggest that privacy problems arise when users provide confidential information (first name, last name, address). However, recent studies have shown that even “anonymous» users allow digital platforms to reconstruct their personal identity. An example of this Netflix, a company that operates in the distribution and production of movies, television series and other entertainment services by means of the Internet. In 2009, Netflix was accused of violating the anonymity of some users who had rated movies and television series by registering only with their ID number [64]. This brought forward a problem already familiar to computer scientists: even in anonymous databases, where the most sensitive information is removed, harmless but idiosyncratic information is enough to identify a user. Identification involves a process of crossing different data sets that work through precise combination to restrict the identification field of the individual user [65]. At best, they can be used for specific advertising policies. The danger is that buyers can sell the same data, and then use it to infer future behaviors that can lead, for example, to the denial of a credit application or a job [66].

In general, users’ concern about the use of their data seems to increase as they perceive less control over it. Recently, three other tech giants, Google, Apple Inc., and Amazon.com Inc., have come under scrutiny for making their employees listen to voice command recordings aimed at digital assistants like Google Assistant, Siri, or Alexa (at the time of writing this report, US and European regulators are investigating possible privacy violations.) Despite initial justification by these companies, which alleged that their intention was to further improve the service provided, Google and Apple have suspended the program, while Amazon has announced that it will change the conditions of use of the device, enabling the option of not participating in the registration service (opt-out) [67]. However, concern still remains high. As some reports show, the ability of users to remove themselves from this type of recording is diminished by a lack of knowledge of its existence and the options that guarantee that the user has consented to the service in question [68]. The latter is linked to another matter of great importance for privacy: dark patterns. This term refers to graphic interfaces that can confuse users, making it difficult for them to express their current preferences, or even manipulate them and lead them to perform certain actions.

A classic example of a dark pattern is a web page that offers the opportunity to subscribe to a newsletter, presenting the ‘I accept’ window in a much easier way to find than the ‘No, thank you’ window. In the worst cases, these websites are designed in such a way as to suggest that, to continue browsing, you must subscribe to the newsletter. More aggressive examples may include purchasing on web pages that place products not selected by the user in the virtual ‘basket,’ which the user will have to patiently eliminate to avoid purchasing them. Some studies have shown the proliferation of these misleading paths among the most popular shopping websites [69]. Dark patterns are highly pertinent to the purposes of of this study, as the process of leading users to make a certain decision increases the amount of data collected.

Paradox of privacy and empirical data

This idea of exchanging data collection for incentives in the form of services has been defined in literature as the «privacy paradox.” Although users acknowledge concern over the dissemination of their information, more and more are sharing their data. To understand the reasons for this paradox, it is useful to conduct some empirical analysis, and thus compare the type of knowledge that users have with the use of their own data by companies. This information is in turn relevant to measure the real will with which consumers disseminate their information. If it is true that no user is really “forced” to share information, it is important to know the level of knowledge surrounding the exchange. A free will marked by ignorance can hardly be considered free.

Therefore, for our purposes, it is helpful to understand consumer perceptions. To do this, we quote here the data collected by the Pew Research Center, for US citizens, and the Eurobarometer data for those in the EU. Regarding the former, a 2018 investigation demonstrated that around 74% of US Facebook users were unaware of the fact that the digital platform classified their interests (a necessary strategy for the ‘target’ advising,’ as analysed in chapter 2 of this report) until they were directed to the “your ad preferences” page to conduct the survey. Once they had access to this section, 27% of the respondents stated that they did not feel represented by the lists produced by the algorithms, compared to 59% who, on the other hand, confirmed the coherence between the categories and their real interests. In any case, 51% reported some discomfort upon learning that Facebook had created that list. A second survey, which extended the sample to users from Twitter and Instagram as well, revealed that they were aware that it would be relatively easy for the platforms to track their habits based based on the data collected. However, the process by which algorithms produce these analyses and the way third-party companies use material collected by Facebook remained unknown to all outside the proprietary companies [70]. The results of this survey imply that more than 70% of the interviewed population remains ignorant of the categorisation of their interests by digital platforms and that, once discovered, more than half do not feel comfortable with it.

In regards to Europe, we will use a report published by the Eurobarometer on data protection, the result of a survey of citizens of the 28 EU Member States in 2015 (before the imlementation of the General Regulation of Data Protection (RGPD)) [71].

According to this survey, 31% of respondents believed they have no control over the information that is provided online. Concern did not arise from the collection of these data by private companies alone, but also from governments. Regarding the awareness of the users about the collection of their data and its use by the platforms, only half answered that they were always aware of the data collection methods and their potential uses when requesting private information. Similarly, only 20% of respondents said they read their online privacy statements in their entirety before giving consent; most of those who admitted they did not read them argued that they were too long. Thus, these statements are considered too complex and unclear (Luxembourg 52%, France 47%, Spain 46%).

The State

Government control adds further and no less menacing risks to the one coming from the private world. In the United States, as early as 2000, the Federal Trade Commission had recommended to Congress that online privacy be upheld [72]. Despite this, after the attacks of September 11, 2001 on the Twin Towers in New York, attention turned to the issue of security, leaving privacy in the background. Meanwhile, the digital economy continued to gradually capture government interest because they understood that behind this sector was the possibility of having greater access to data and consequently, greater control over persons. The massive collection and analysis of personal data has strengthened governments, which today probably know more than ever about their citizens.

In fact, Laura Poitras, director of the documentary film Citizenfour, which recreates the whistleblower scandal reported by Snowden, in an interview with The Washington Post in 2014 stated that «Facebook is a gift for intelligence agencies» [73]. The type of information it offers gives governments the ability to anticipate protests and even preemptively arrest people they think will take part in them.

For the past 20 years, the US government has activated an electronic surveillance program operated by the National Security Agency through which they collect data from Google, Facebook and other technology companies [74]. This program, called ‘PRISM’, is used to track online searches, email content, and conversations between users. The platforms have denied that they collaborate with him, and have reiterated that the information they offer to the government is always in compliance with the law and the privacy of the people. [75]

However, as we will see later, today’s greatest threat to citizens’ right to privacy comes from the union between Big State and Big Corporation. On one side, digital platforms have an insight that allows them to gather a large amount of information; on the other, the State potentially holds the authority to access this data. For this reason, it is urgent to propose a solution that is not aimed simply at regulating these platforms, but also at reducing their power: power that ultimately could be transferred to the authorities to the detriment of individuals.

‘Notice and Consent’, Paternalism and ‘Nudging’

In the face of such a bleak picture, it is worth focusing on possible exit strategies. Until recently, the most widely used approach to privacy was Anglo-Saxon, characterised by empowering the individual user as much as possible in order to avoid exaggerated interventionism and safeguard people’s freedom; this model is typically defined as ‘notice and consent.’ In practice, it was based on consulting users on what type of data collection they wanted in what we could call privacy self-management, guaranteeing the right of choice and a secure transfer thanks to appropriate technologies and procedures. The objective of this approach was to increase user literacy in terms of privacy. Despite the noble intention, there are several reasons that have led to its rethinking. Primarily, the fact that data in today’s day and age can be stored through any online service has led to the human impossibility of exercising a continuous process of rational decision-making and consent. In addition, an increasing amount of pop-ups that may warn us of a privacy problem are perceived as an obstacle that must be overcome in order to obtain a service. To all this, we must add that the permission must always be given in real time, which makes decision-making difficult and increases the risk that the privacy notice will be ignored.

Finally, it does help the situation that the type of questions asked to consumers are often too complex, or use extremely technical jargon. Academic studies show that the information provided to users is too voluminous and intricate for them to read, understand, and make decisions that reflect their values, preferences, and interests [76]. If users only related to a few ‘realities’ that approach might still be conceivable, but in a world where they have dozens of apps on their phones and are constantly connected to other devices, at home and at work, such a solution is not realistic. Very often, users confirm the pop-up without reading, hoping that nothing serious will happen. All of this invites us to discard the ‘notice and consent’ approach.

At the other extreme, we find a paternalistic approach, which aims to significantly limit the ability of companies to collect user data. It also has some important drawbacks, such as not recognising the heterogeneity of user opinions on the use of their data. In the midst of those who are particularly concerned about their privacy, there are others who are willing to provide information about themselves in exchange for services. Therefore, an excessively paternalistic approach carries the risk of blurring this distinction and thus reducing consumers’ freedom of action.

The third possible approach is that of paternal liberalism, associated with the concept of nudging, developed by the Nobel Prize in Economics Richard Thaler [77]. This concept, applied to the context of privacy and data protection, is translated specifically into the default settings. Its advantage lies in its status quo bias, whereby once a certain decision is made, there is an exaggerated preference to maintain it. In general, this bias is analysed with respect to the choice of pension funds, but recently has been considered in the context of privacy. An interesting fact for our case is that most of the digital platforms that collect data set the default to maximum disclosure options by users. Therefore, a law requiring these compilers to set the default options to the most conservative in regards to the disclosure of sensitive information, unless the user decides otherwise, could guarantee better protection of privacy. Recently, a report published by the Stigler Center at the University of Chicago suggested that when consumer preferences and expectations (gathered through scientific studies) coincide with company practices, these options should be adopted by default. However, when consumer preferences and expectations differ from those of companies, it would be more appropriate to use consumer options as a default rule, leaving room for flexibility in case companies are able to convince those about the benefits of his proposal [78]. We will expand in chapter 4 on the consistency of this approach with the reform that the GDPR has advanced. Thus, its proposal seems compatible, on the one hand, with the diversity of user preferences, and on the other, because it prevents digital platforms from manipulating users to make decisions that threaten their well-being.

It remains to be seen to what extent the nudging proposal respects the principles of classical liberalism, a perspective from which this report intends to approach the debate over digital platforms and privacy. First of all, it is important to underline the difference between this form of liberalism and other more extreme formulas that go back to ‘anarcho-liberalism,’ which in its technological aspect, has been defined as ‘crypto-liberalism’ [79].

These latter topics encompass rather extreme, and probably idealistic, views of the potential of technology to strengthen freedom. In contrast, classical liberalism recognises the value and usefulness of a regulatory framework capable of respecting autonomy and facilitating voluntary and profit transactions between individuals. In fact, these rules are configured to protect that individual autonomy, essential for people to be able to choose freely [80].

In unraveling the merits of this report’s proposal, the idea of nudging that aligns with liberal paternalism is based on the fact that there exist ‘experts’ capable of framing options, so that personal preferences coincide with what the users ‘should’ choose for their own good. Traditionally, the idea of a group of experts who choose on behalf of the rest of the population contradicts the specific principles of liberal autonomy, in which people exercise freedom through the possibility of making mistakes, growing in responsibility and capability.

Libertarian criticism of the effectiveness of these ‘experts’ is correct, even running the risk of forgetting another important dimension. If we can argue that the ‘experts,’ or the government, represent a threat to individual freedom and autonomy, we must also bear in mind that, in the context of online privacy, the user’s choice never occurs in a totally neutral way. The suggestions of the ‘experts’ can create distortions, are opposed by a ‘default’ option designed by and for the exclusive benefit of digital platforms (to collect as much data as possible). In this context, solutions that cling to ideological motivations must be avoided.

Therefore, the proposal of default rules based on consumer preferences is consistent with a liberalism that is not closed tout court to a set of rules. In this case, the ‘experts’ would be used to scientifically identify the average preferences of the users, and suggest predetermined options in accordance with this data, not with personal or institutional opinions (or unspecified State reasons). In addition, this proposal must not exclude those users willing to share their information.

In this sense, legislation capable of defending the diversity of preferences, and therefore choice of consumers, while simultaneously preventing companies from operating in the digital sector unrestricted, focuses on a good solution, consistent with individual freedom.

CHAPTER IV. THE OPERATION OF THE RPDG

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is, without a doubt, the most ambitious bill in force on privacy and data protection. It has been applied in the EU member countries since May 2018, and, little by little, it is also becoming a reference for similar laws in the rest of the world. For this reason, its analysis is essential for the purposes of our report, which will not carry out a detailed study, but will highlight aspects related to its consequences for users and companies.

The RPDG has imposed strict rules for data processing by digital platforms, and has created significant rights for users. The Regulation defines personal data as all information related to an identifiable or identified person —also called «interested party» (Art. 3) — and provides for greater protection for sensitive information such as race, health status, sexual orientation and background penalties. Its applies to all entities registered in the EU, including foreign entities that process personal data of community residents, whose activity relates to provision of goods and services, as well as the collection of data intended to track behavior. The national authorities in charge, normally the different privacy guarantors, exercise a supervisory function; in the event of non-compliance, they can issue fines of up to 4% of a company’s total income, or 20 million euros, depending on which figure is greater. The GDPR also gives trade associations and non-profit organisations the ability to initiate a class action that allows certain companies to be sued on behalf of consumers.

Regarding the subjects dedicated to data processing, the GDPR differentiates between the “data collectors” (owners of the treatment) and the “data processors” (data controllers) (Chap. 4 – Art. 24-43 ). The former determine the purpose of data collection and the means for its treatment, while the latter, after receiving it, are in charge of managing it. Owners are generally obliged to fulfill a number of duties, including that of demonstrating compliance — not only of themselves, but also of those responsible, which supervise behabior, and disclose the existence of any third parties that will manage consumer data. It is always the owners who then must inform them of how those will be used, for how long they will be retained, and how their inherent rights will be respected.

Regarding the foundations on which the entire regulatory structure is based, we must refer to two principles (introduced in Art. 25): that of ‘privacy by design’ and ‘privacy by default.’ The first involves a conceptual approach that requires companies to start a project, providing the correct configuration from the start to protect personal data, such as the use of pseudonyms or the minimisation of the information present in the structure of products and services. This principle revolves around the idea that problems should be addressed in the design phase to avoid risks, in both the centrality of rights and responses to access requests.

On the contrary, with the principle of ‘privacy by default,’ efforts have been made to ensure that, by default, companies have to process personal data only to the extent necessary for the stated purposes and for the period strictly required. This would allow the user to receive a high level of protection, even without limiting the collection of data (for example, enabling the ‘opt out’ option). In this sense, we can see how these principles are consistent with the nudging approach presented in Chapter 3. Their introduction also forces companies to prepare an assessment of ‘privacy impact’ each time a project uses data processing. This cannot be underestimated, since it generates a series of costs for companies that we will discuss later.

While the GDPR has increased regulatory obligations for companies, it has also brought forth a number of rights for consumers. Thus, the interested parties can request that the owners and managers provide an explanation of the type of data they are collecting and how they will be used in the future, as well as request that their data be corrected or deleted. Although the owners can share the information of the interested parties with third parties to fulfill the initial objective of the treatment, they cannot do it for a different purpose, unless the consumer allows it or the owner uses a new legal basis. Personal data can be transferred outside the EU, but generally only to those countries where privacy protection is in effect in an equivalent way (a decision that depends on the European Commission).

Finally, the GDPR requires companies to apply certain data security practices. Its holders, for example, should dedicate themselves to “minimisation,” which consists of collecting only the data necessary to carry out a certain task, and to keep it only for the time necessary to fulfill its purpose (unless they are used in the public interest). Companies must also implement appropriate technical measures that guarantee the security or limit the risk of an unauthorised leak or disclosure of personal data. Although it does not impose any specific measure, the GDPR recommends (Art. 32) the use of certain techniques such as pseudonymisation and data encryption, or a process to verify the effectiveness of these technological and organisational measures [81].

After this non-exhaustive analysis of the technical aspects introduced by the GDPR, we can highlight some of its results to date:

- The GDPR standardises and strengthens the rights of citizens in the collection and processing of personal data, and at the same time reinforces the supervisory role of national data protection authorities, since it gives them the opportunity to monitor compliance and fine any breach.

- The GDPR is definitely a step forward from the point of view of consumer respect. The principles ‘by design’ and ‘by default’ oblige public bodies, organisations and companies to change the way they approach the management of personal data, and to consider privacy in the very design of a product, preventing more information from being collected than what is necessary. This point has represented a significant investment in web page design, which are often structured so that users will reveal as much personal data as possible (given that the platform practices ‘target advertising’ or sells data to a third party for behavior prediction).

- The GDPR offers new possibilities for users to manage their data and request information about what is stored and how it is used. With the option of downloading whatever personal data a company has on himself, an Internet user can control what the platforms retain and decide whether to export them to other services. However, user consent is required for personal data to be processed, with a clear purpose stated for the data. Compared to the past situation, in which the user’s consent was much more generic, the GDPR provides a specific delimitation of the different purposes, so that the user can decide to grant permission based on the interest they have at any given time. At this point, it will be up to national regulators and courts to decide how the provisions on user consent are interpreted. In fact, digital platforms may set the demand for data in such a way as to incentivise consumers to make the decision that benefits them the most (obscure patterns).

Not only does the GDPR benefit the consumer, but it was created with the intention of promoting positive development in the digital sector as well. Compliance with the new provisions could improve data management and inspire new business models. A global investigation carried out by the IBM Institute for Business Value on executives from different industrial areas has indicated that managers perceived the new legislature as an opportunity to gain the trust of consumers. Thus, respect for the GDPR would function as a distinctive element in a competitive environment, in particular by strengthening the relationship with customers [82].

On the other hand, the implementation of the GDPR has involved significant investment for companies in terms of finance and technology. Each, regardless of size, had to incorporate software, technical support, and legal advice to ensure compliance with the law. New provisions on data processing and strict deadlines for identifying any security problem and reporting to authorities have been particularly costly for large companies. Some studies have revealed that the total amount spent by Fortune 500 members amounts to about $7.8 billion, including technical investment, expert recruitment, and staff training [83].

The need for additional staff continues to present itself as one of the most problematic aspects of the new regulation. The GDPR provides (Art. 37) that each service that involves monitoring of large-scale stakeholders is required to appoint a ‘data protection officer’ (DPO) (Art. 37) — the person in charge of complying with the treatment regulations. The interpretation of what this means ‘on a large scale’ continues to be interpreted, and the last word belongs to the company. Given this uncertainty, most companies may choose to hire additional staff as a kind of insurance policy against non-compliance.

Possible confusion generated by the GDPR would not only affect large corporations or multinationals. In fact, the real problem lies in small and medium-sized ones, where even a modest expense could take a large toll. For this reason, the business plans of the SMEs must contemplate these additional costs, dedicated to the training of workers and the purchase of the software and hardware necessary to comply with the RPDG.

Small and medium-sized companies also face one more obstacle, linked to the indirect advantage that GDPR gives large companies in terms of consumer confidence. Established companies not only have funds that allow them to ensure GDPR compatibility, but also a large number of customers who will consent to share personal data, since they recognise and trust these brands. With the new regulation, smaller companies and start-ups would face more difficultly, both in terms of the investment required to comply with the GDPR, and in gaining consumer confidence when competing with larger rivals that dominate the market.

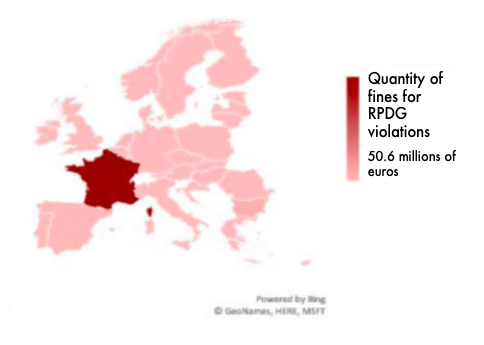

Born with the intention of defending consumers against particularly aggressive privacy policies of digital platforms, the debate on the effectiveness of the GDPR remains open. For example, the high fines imposed by national authorities for violations of the GDPR amount to more than 55 million euros, most of which come from a 50 million euro French author’s complaint (CNIL) against Google. This fine, the highest for violating the GDPR, covered complaints filed in May 2018 by the Austrian organisation “None of Your Business” and the French NGO “La Quadrature du Net” for the creation of Google accounts during the configuration of mobile phones with Android operating system [84].

Graph 2. Sanctions of the RPDG

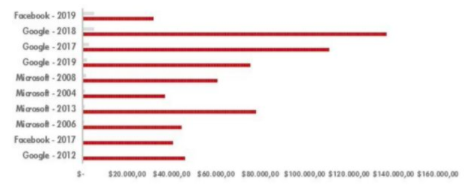

With these exceptions, the vast majority of penalties have affected small and medium-sized companies. This is interesting because, on the one hand, it seems to confirm that SMEs, which should have benefited from greater control over big technology, are paying relatively high costs in terms of compliance or penalties; on the other hand, it suggests aside from a few exceptions, the big players have found a way to align themselves with the new regulation (especially because they could afford to spend more money in legal resources). In order to extract some final considerations, the current panorama reveals that GDPR regulation has not guaranteed greater competition within the digital platforms sector, but, rather, obstructs new companies, consolidating the position of incumbents. Regarding privacy protection, the greatest risks appear to come from the largest companies, as seen in Chapter 3. The fact that most of them have not yet been sanctioned for violations of the GDPR indicates that it is unlikely to be deterring misconduct. This last hypothesis becomes stronger if we refer it to the world situation. The relationship between Big Tech revenues and the sanctions of the European Commission and the Federal Trade Commission (Consumer Protection Authority of the United States), for reasons not only related to privacy, demonstrate that these companies are unlikely to perceive the penalties as a threat.

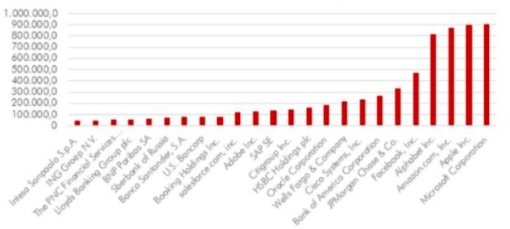

Graph 3. The Major Fines and Earnings- European Commission and Federal Commission of Commerce

Large fines and extensive enforcement actions have been largely absent; indeed, during this period, new forms of data collection have emerged, including the reintroduction of Facebook facial recognition technology in Europe and Google’s efforts to collect information on third party websites [85].

As we can see in Figure 5, between Google, Facebook and Microsoft (the Big Techs most sanctioned to date between the European Commission and the FTC), only the social network has received fines that approach almost 10% of its annual income: the fine of 5 billion dollars that Facebook received in August 2019 represents 16% of the profits of the first six months of that year.

Through this analysis, we do not defend tougher sanctioning policies, but quite the opposite: monetary punishments are almost ineffective in neutralising these companies if not accompanied by real actions to encourage competition.

CHAPTER V. POSSIBLE FUTURE SOLUTIONS

Given the lack of a domino effect that many politicians and academics expected after the GDPR, more voices have arisen with new proposals to solve the lack of control within the data market. As in Chapter 3, we can distinguish between those who propose greater regulation by public institutions, and those who believe that the key lies in empowering people to choose their position with respect to each platform.

Regulatory and antitrust proposals

Antitrust laws have often been configured as the most efficient method of controlling large corporations and limiting their power, expanding competition in the marketplace, and generating innovation. Google itself achieved its current dominant position thanks to the limits that the American and European public authorities placed on Microsoft in the late 1990s. To quote Professor Luigi Zingales, «Today’s monopolies are yesterday’s start-ups» [86].