A lot has been written and researched regarding the effects of monetary policy -especially unconventional one- on inequality, but no consensus has been reached. Each time a new paper studying this conflictive relationship is published a new array of evidence is uncovered to counterattack those newer arguments. Hawks, Keynesians and Monetarists have heavily relied on this evidence to prolong their debates and try to win over the argument about the effects of monetary policy on inequality. Not curiously, very few academics have moved from their initial positions in these debate throughout the last decade.

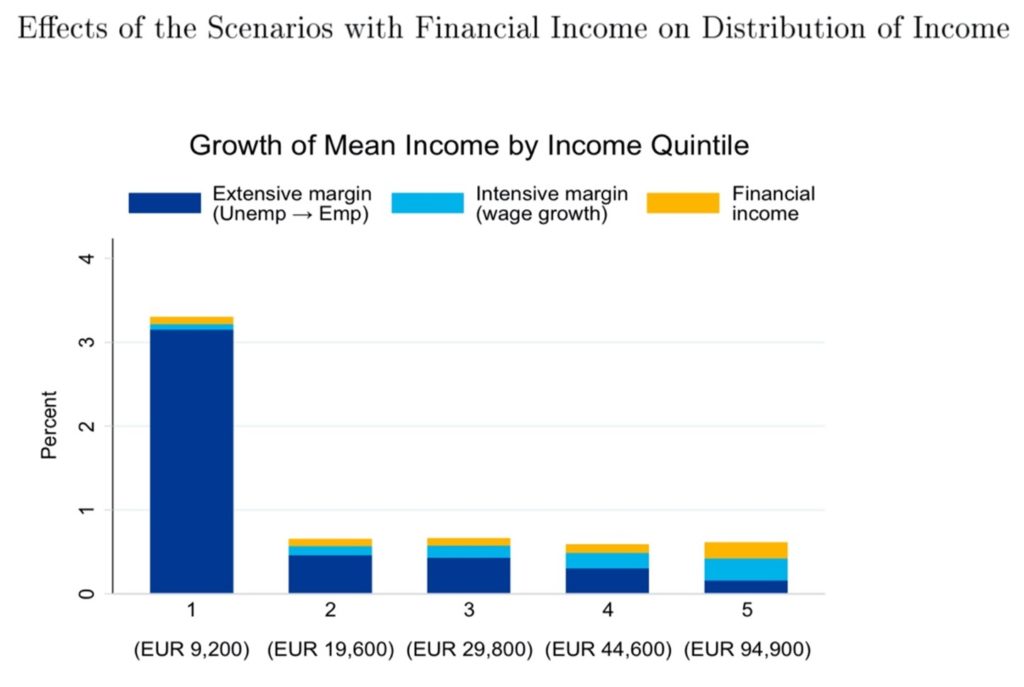

In 2018, the ECB published a working paper which has become very well known since then. In this paper, the authors quantify the effects of quantitative easing (QE) on wealth and income inequality in the euro area. They study these effects by analyzing income and wealth of individual households through income composition analysis, portfolio composition and other channels of earnings. Their main conclusion is that unconventional monetary policy, of which QE is its main representative, has no relevant effects on wealth inequality, but very significant effects regarding income inequality. The main explanation for this the authors provide is that thanks to QE programmes, many unemployed people were able to find a job, and by becoming employed, their earnings levels rose significantly, so, even though if income levels of top earners also rose, the income of the former increased at a faster rate, reducing the income gap between the various quintiles of income distribution in the vast majority of countries in the Eurozone. A year after the first QE program, the Eurozone income Gini coefficient fell from 43.1 to 42.9, to which the authors attribute the majority of the decrease to unconventional monetary policy effects on the real economy, as faster economic growth and employment levels recovery. However, they recognize that the reduction in income inequality brought by QE is small in comparison to the previous increase in that indicator during the Great Recession and the Eurozone recession following suit.

As I have previously written in this same space, many other factors as globalization or fiscal policy can affect inequality in a more notorious way than monetary policy, of which its many effects concentrate on other variables as unemployment levels or GDP growth. However, as the mentioned paper shows, consumption inequality is heavily reduced thanks in part to unconventional monetary policy. This can be explained through a simple mechanism: workers with temporary contracts, workers with low wages in certain industries and interns are the first ones normally to lose their job in midst of a recession, and they are also the ones with highest marginal propensity to consume, due to their lower wages. So, when after being unemployed they find a job again, their consumption levels rise by a larger proportion than those of top income earners in the recovery phase, making the consumption inequality gap smaller. So, it could be asserted that the stimulative effects of QE on consumption are particularly notorious because the incomes which are proportionally more affected are those of people in the lower part of the distribution, with a larger MPC.

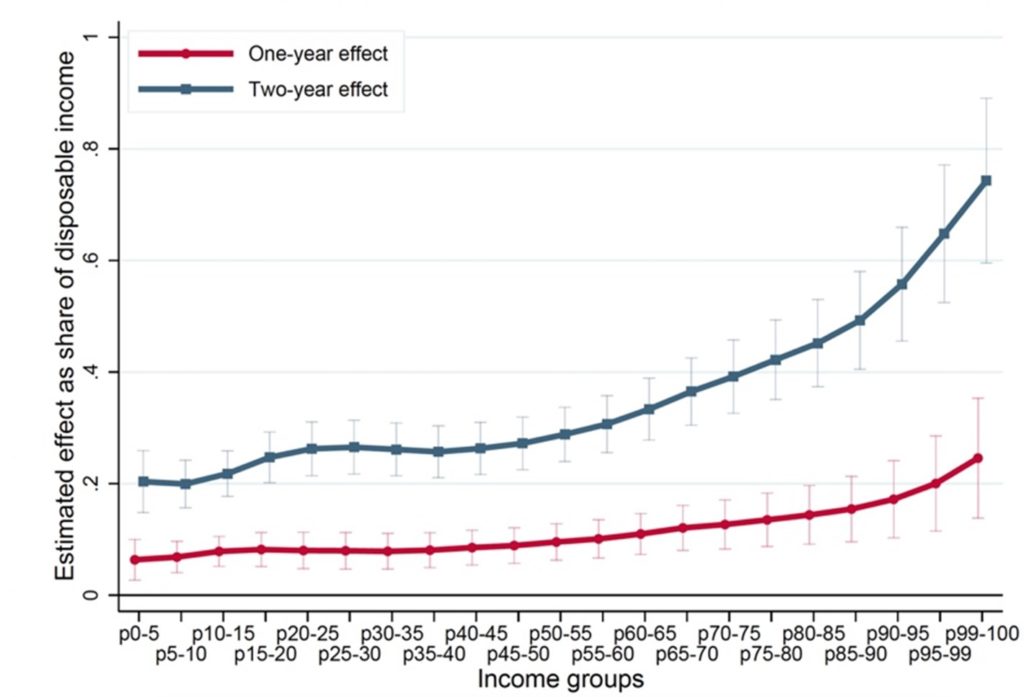

On the other hand, a paper by Andersen et al. has recently been released studying the effects of soft monetary policy on inequality in Denmark. The researchers’ main data source are individual-level tax records for the whole population of Denmark from 1987 up to 2014. The Danish monetary authorities have, since the establishment of the ECB, had a commitment to exchange rate stability, which means that when the ECB changes its leading interest rate, the Central Bank of Denmark usually varies its rate too, in order to restore the rate differential consistent with the commitment to a fixed exchange rate. This allows the authors to use changes in ECB policy as an independent variable of changes in Danish interest rates and study the effects of their variations on inequality trends. They find that soft monetary policy has contributed the most to increasing employment in low-income groups, but, however, other components of disposable income, as stock market incomes, lower interest expenses, etc. are affected in a larger way by this monetary policy movements, leading to an increase in income inequality. The authors quantify these effects in the following way: “a decrease in the policy rate of one percentage point increases asset values by around 20% of disposable income at the bottom of the income distribution and by around 75% of disposable income at the top over a two-year horizon.” This shows that consumption and wealth gains of soft monetary policy are very unequally distributed, at least in the case of Denmark, which contrasts with the ECB study summarized beforehand.

As it has been shown, unconventional monetary policy has diverging effects on inequality, depending on the time, country and type of policy developed. However, if there’s one clear thing is that, at least in the short run, it has contributed to prop up the incomes of those in the lower quintiles of the income distribution by increasing employment levels.