In the previous article titled Crisis on the defence budget, I analysed the the budget proposal of the sitting Government of Spain, but, now, it will be the polls who will pass judgment on this matter. With the call for new elections, we return to the starting place. And the need is pressing. In the aforementioned article, I explain the need for a larger budget in Defence, highlighting some specific cases in which we were already late. However, this increase must be based on several premises.

First, effectiveness. That is, the “ability to achieve the desired or expected effect”. To achieve this, we must first identify the threats we face. In Spain, the key document in this regard is the National Security Strategy. Having carried out this analysis, the next stage is to specify the best tools for the Armed Forces to fulfill their mission, which is none other than the defence of national sovereignty.

The second premise, efficiency. As any public entity, financed by taxpayers, the Ministry of Defence must maximize its results with the available resources. In this sense, it seems that some of our neighbors have found the solution. The so-called Smart Defence or Pool & Sharing, or distribution of military capabilities, consists of an initiative already being carried out by several countries in our environment. The best example, the Franco-British agreement of November 2, 2010. Some of the measures it contains are:

– Budget of 100 million euros for military R&D.

– Greater integration of the Franco-British branch of the European company MBDA.

– Creation of a combined rapid reaction force.

– Harmonisation of arms purchase processes —in order to strengthen the ties of the industry of both countries.

As Bernardo Navazo points out, the problem faced by European governments is the ‘defense trilemma’. In his opinion, «no European State can now pay the expenses that all military capabilities require in response to the broad spectrum of conventional and unconventional threats … nor provide for total security and defence». Therefore, “the choice is no longer between maintaining or sharing capacities and losing autonomy in their use; the real choice is between sharing capacities, even assuming some loss of autonomy, or not being able to dispose of them”[1].

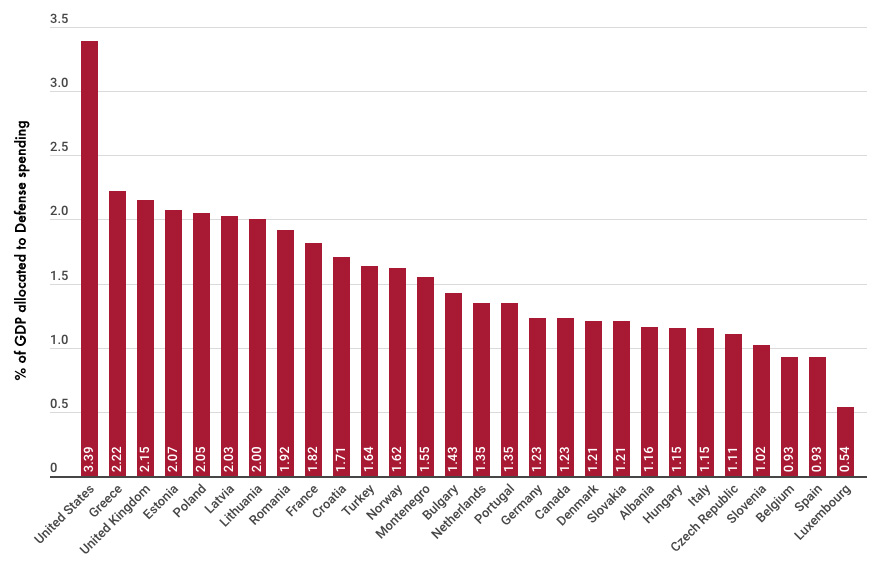

Therefore, the underlying issue is not so much to spend more —even if this was necessary—, but to spend better. However, this approach has its drawbacks. On the one hand, within the Defence framework, there is no balance between supply and demand. This is a very restricted market. On the demand side, we can define Defence as a public and intangible good, in which there is non-exclusion —available to all— and non-rivalry —its use does not diminish that of another person. These characteristics favour the problem of the free rider. This term refers to those consumers of indivisible goods or services, especially public, as it is the case, and who benefit from them without paying any consideration. NATO is the paradigmatic case. Of its total budget, the United States contributes almost 72 percent. This means that the rest of the countries that comprise it (28 signing states), and especially those that do not even contribute what has been agreed —the famous 2 percent of GDP—, act as true free riders. As we see in the graph, only seven countries comply. And that, including those with an asterisk —Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania—, which have laws that oblige them to do so.

Table 1. Defence spending (% GDP)

This phenomenon is one of the main problems faced by the thesis of sharing military capabilities. Another of its failures is found in its initial hypothesis: the impossibility of European economies to pay —and maintain— the necessary Defence programmes for their national interests. The weakness of this statement is that it does not contemplate a general tax reduction scenario. In fact, it is refuted with the U.S. case, which stands at record growth and collection figures.

If the government undergoes a true ‘tax revolution’, it will have sufficient resources to devote a part of them to defence purposes. With this, two objectives would be achieved: increase public spending on this front, and reduce the tax wedge that taxpayers bear.

A final obstacle of this theory, and perhaps the most important, is the lack of communion of interests. As Hayek points out:

«There should be few difficulties to plan the economic life of a family, and relatively few for a small community. But when the scale grows, the level of agreement on the gradation of ends decreases and the need to resort to force and coercion increases»[2].

If the Government undergoes a tax revolution, it will have sufficient resources to devote part of them to Defence purposes

This difficulty highlights the magnitude of the task that the sharing theory implies. And more so, if it is an area such as Defence. Despite all these objections, it has good foundations, and as Navazo emphasises, there is room to cooperate in certain tasks, especially in those furthest from the first line of combat. However, the loss of sovereignty that such collaboration implies should not be overlooked. This, coupled with the variability of the strategic environment and the generalized refusal of societies to globalism, foresee some unflattering beginnings. In short, Spain, as a State, not only has to spend more on Defence, but better. The sharing theory is an advance in this objective, but it has to be understood as a complementary policy, not a substitute of public spending in Defence. For this to be achieved without emptying the pockets of the Spaniards, the government which results from the elections must read Laffer’s work carefully.

References:

[1] NAVAZO LÓPEZ, Bernardo (2013). “The impact of the economic crisis on Defence: autonomous irrelevance or combined action», Working paper nº 72/2013, OPEX, 2013, Madrid.

[2] HAYEK, Friedrich A. (2011). “The Road to Serfdom”, Alianza Editorial, Madrid, p. 326.