Abstract

The ‘Recovery Plan for Europe’ launched in 2021 is aimed at setting the EU economy back on its feet after COVID-19 and modernising a society left behind by technological transformation. It is also surreptitiously intended as another step towards making Europe more federal. The Plan consists of a €1.3 trillion seven-year budget paid for by old and new taxes and an €807 billion ‘Recovery and Resilience Facility’ financed by an issue of European Commission bonds. The total sum is no less than €2.02 trillion. Mutualising EU states’ debt is what Hamilton did for the nascent United States. This is an industrial policy plan with increased fiscal pressure and a careful avoidance of the free market. The reservations of Mises and Hayek regarding wholesale planning are gainsaid with a complicated to-and-fro mechanism to control waste and adapt to shocks. The resulting centralisation will be another element in the slow creation of a European state.

Keywords: EU Recovery Plan, Next Generation EU, planned economy, industrial policy, federal Europe

1. The ‘Next Generation EU’ plan

In February 2021 the EU Commission approved a plan originally proposed by then Chancellor Angela Merkel and recently re-elected President Emmanuel Macron.1 It thus launched a ‘Recovery Plan for Europe’ with two overt aims: to set the European economy back on its feet after COVID-19 and to modernise Europe and put it on a par with the most advanced economies. Underneath, however, there is a further implied aim: to have the European Union take another step on the path to becoming a national state. This poses the question whether this ambitious Recovery Plan will make Europe freer and more prosperous (European Commission, n.d.).

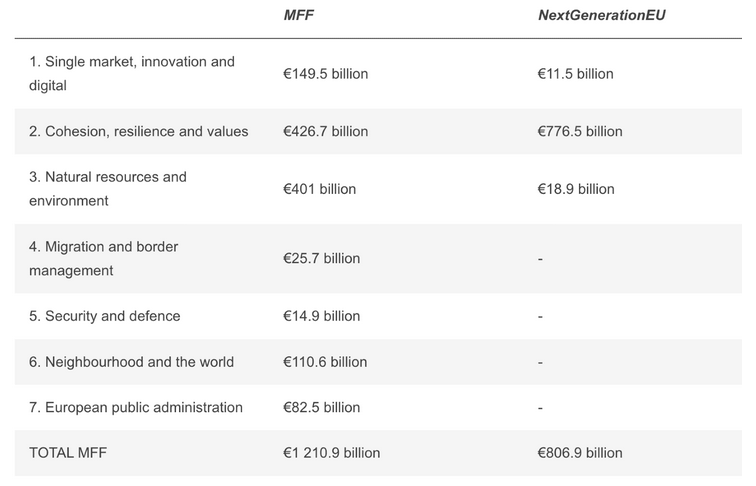

The Recovery Plan consists of two parts: (1) the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) or EU budget covering seven years from 2021 to 2027; and (2) a once and for all fund called ‘Next Generation EU’ (NGEU) containing a ‘Recovery and Resilience Facility’ (RRF). In current prices, the total expenditure for the seven years covered by the MFF is set at €1.2109 trillion, financed by old and new taxes. The RRF, also at today’s prices, will amount to another €806.9 billion, to be financed by the Commission borrowing on the capital markets on behalf of the EU. If we add this facility to the multi-annual budget, this Recovery Plan as a whole will come to the mind-boggling sum of €2.018 trillion.

Clearly, the Recovery Plan aspires to be much more than a package of measures to help Europe recover from the effects of the pandemic. In the words of the EU Commission,

NextGenerationEU is more than a recovery plan. … It is a once in a lifetime chance to emerge stronger from the pandemic, transform our economies, create opportunities and jobs for the Europe where we want to live. We have everything to make this happen. (European Commission The Recovery Plan for Europe, Introduction)

Obviously, this shower of money is more than economic in intent. No doubt there was a need to provide relief to people hit hard by the pandemic and the restrictive measures taken to fight it. However, as suggested by the political enthusiasm infusing the above declaration, COVID-19 has become an occasion for moving forward towards the eventual creation of a European state. By pandering to the belief that only government can be trusted with the post-COVID-19 reconstruction, the Commission is in fact working towards the goal of having Europeans unwittingly accept the creation of a unified polity capable of claiming a place among the great powers of the world.2

Hence, before examining the political dimension of the Commission’s plan, we must analyse it as an industrial policy document. The idea that it is a proper goal of government to take a leading role in the industrialisation of the country has its roots in the Continental European and American reactions to the British example of economic progress during the so-called Industrial Revolution, based on private technology and capitalist manufacture rather than state commerce. Continental practice was generally based on Crown privilege and aristocratic custom rather than unregulated innovation and popular consumption, as in Scotland and England, where there was no Colbert or Bismarck. True, the Encyclopédie (1751–1772) was presented as a vademecum for aspiring industrialists, as its subtitle promises: Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. On the Continent of Europe and in the United States during the nineteenth century, the weapons used for industrialisation were public initiative and foreign trade barriers, with varied success. After the Great Depression and the Second World War, the policy changed to creating national industries or nationalising existing ones, with dismal results. Then the era of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher dawned, and industrial policy went out of fashion. At present we are witnessing a return to governmental industrial policy. There is no better example than the post-COVID-19 Recovery Plan of the European Union. European industrial policy has two traits: a belief in the ability of bureaucrats to mark the way of the future for national economies, and a thick undergrowth of institutional and financial arrangements to assuage special interests.

As to macro policy, the general object of the MFF and the NGEU project is ‘to make Europe greener, more digital and more resilient’. It is normal for public organisations and private companies to proclaim a mission statement, usually devoid of practical content. But when the organisation is pulled by conflicting interests, the mission statement runs the risk of being reduced to strategic confusion by trying to satisfy everyone.

Table 1. Multiannual Financial Framework 2021–2027 and Next Generation EU total allocations

Source: Table from the European Commission

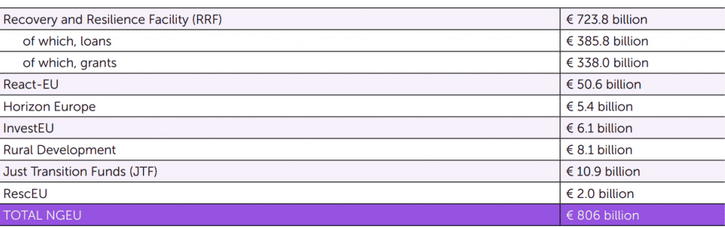

The NGEU plan is difficult to follow for the variety of institutions, funds, and acronyms it compounds. (See Table 2) What is clear is that it consists in a huge sum of money. This bonanza will finance an abundance of industrial policy projects, some entrusted to the Commission, most to the Member States (MS). Of the Europe-wide projects, the main one is REACT-EU, an accelerated disbursement of cohesion funds totalling €47.5 billion to redress the harm caused by COVID-19. The programmes entrusted to the MS come under the ‘Recovery and Resilience Mechanism’ (RRM) and are assigned up to €67.5 billion, conditioned on the success of the plans proposed by national governments, with a maximum of 6.8 per cent of each gross national income.

Table 2. The Next Generation EU programmes

2. Levying new taxes, no role for the market

The aims of the RRM are summarised in no fewer than six ‘pillars’. The two most important ones are (1) ‘green transition’ and (2) ‘digital transformation’. Subordinate aims are (3) intelligent, sustainable, and integrating growth; (4) social and territorial cohesion; (5) health, economic, social, and institutional resilience; and (6) forward-looking education. Most economists accept the old Tinbergen admonition that each policy instrument should be directed at one single policy goal. It will be difficult to combine these six goals, especially because they are set in terms so wide that national proposers of projects and Commission adjudicators and controllers will find it difficult to be sure they are respected in practice. In any case, the Commission off its own bat makes numerous country-specific recommendations semester by semester. There are eight headings under which MS can be admonished: fiscal policies, digital and energy transition, social policies, education, financial markets and banking, labour markets, and taxation.

A stronger Commission with more tasks needs new taxes. Next Generation EU will initially be financed by bonds placed on the world’s financial markets. Those bonds must be serviced and refunded.3 To that end the Commission proposed, and the European Council and Parliament in 2021 approved, three new ‘own resources’, to be added to the existing sources of revenue of the Commission: (1) 25 per cent of the revenues of emission trading in the EU; (2) 75 per cent of the income enjoyed by MS from the carbon adjustment mechanism; and (3) 5 per cent of the reallocated profits of very large multinationals that were avoiding taxes on local profits.4 Taxation is clearly too heavy in Europe. This hampers economic growth and reduces the space of individual freedom. Long historical experience shows that new states rely on more taxes because one of the ways to achieve their national ambitions is through expanded public expenditure.

One striking feature of the Recovery Plan for Europe is that the idea of free markets and free competition is absent. There is no mention of the free market as an instrument of recovery and economic transformation. In fact, the market is mentioned only under the label of a ‘single market’, in the sense of finally turning the EU into a large economic area. The healing powers of market competition and of institutional competition are not understood by the Commission nor more generally in Europe.

3. The example of Spain

This makes the Marshall Plan, often mentioned in this context, an object lesson for the defenders of the present Recovery Plan. The Marshall Plan did signify a profound change in American public opinion in favour helping Europeans recover from the destruction of physical and human capital in the Second World War. It was a generous action that alleviated the balance of payments deficit of countries needing imports from America for which they had no means to pay. However, reconstruction was swifter and more thorough in Germany and Italy than in France and the United Kingdom, where wartime interventions and socialist policies were applied for the rest of the 1940s and even during the 1950s. The German and Italian ‘miracles’ show the healing power of the free market. Ludwig Erhard and Alcide De Gasperi, by getting rid of officious interventions, put in effect an expansion that eluded the social-democratic governments of the two victor countries, in contrast with the vanquished.

The Spanish economy is known to be one of the worst managed in Europe. With growing tensions among its autonomous regions, a structural rate of inflation higher than that of most of its Eurozone companions, a persistently high rate of unemployment, a badly managed welfare state, public deficits among the highest in Europe, and a coalition government incapable of reform, it is surprising that Spain should be among the most successful of the suitors under the Recovery Plan. But it is receiving high praise from the Commission.5 Between 2020 and 2026 Spain is to receive €140 billion under the Recovery and Resilience Facility. The first step is to present a National Recovery and Resilience Plan. Spain was among the first to do so in 2021. It was accepted by the Commission, with some specific recommendations.

For an economist who lives and works in Spain, the document, which was approved with high marks by the Brussels Commission, reads like a fairy tale. The Spanish government has presented it as a coherent plan ‘of investments and structural reforms’ aiming at recovery in the short term, focusing on ‘digitalising and decarbonising the Spanish economy, while reducing the gender gap’. The language is well in harmony with current fashion. The ‘adequate mix of monetary and fiscal policy, together with the Next Generation package’, have brought about a quick recovery. Perhaps the present situation of increasing inflation is not the best moment for praising monetary policy. And saying that Spain has been applying a reform and investment programme for three years does not accord with facts. The government has chosen no fewer than 110 investment projects and 102 structural reforms of its own. The role of the private sector in this transformation will be assured by the presentation of green, digitalised, and gender equality projects, most of which were notin portfolio before COVID-19.

If this is the way the Commission intends to avoid waste, there is reason to worry.

4. The impossibility of a planned economy

As long ago as the first half of the twentieth century, Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek warned of the impossibility of economic planning – literally (Mises, 1975 [1933]).6 The planners had insufficient information and the planned were led astray by misguided incentives. The price system continuously offers such an abundance of information that no individual can gather or transmit it all. Firstly, all-encompassing blueprints such as the Recovery Plan for Europe turn out to be rigid, as the notion of ‘Five-year Plans’ indicates. They are especially exposed to unexpected events, given their rigidity. This is so for the managing of a static economy, but more so for a dynamic economy subject to shocks. Aggregate planning adapts with difficulty to new circumstance. The Recovery Plan for Europe was designed as a response to the 2008 financial crisis and as a springboard for the modernisation of Europe. It first encountered inflation brought on by central banks’ mistaken monetary policy – a possibility not even mentioned in that programme of fiscal expansion. It was then thrown into further disarray by the mega-shock of war in Ukraine and sanctions against Russia. Speak of uncertainty! The Commission knows from experience that the EU is rigid by design. When trying to foresee and shape the future of the EU, the planners in Brussels were led to commit the ‘Khrushchev mistake’ (Spufford, 2010),7 that is, overfunding projects to try to overcome the structural defects of the planned economy, resulting in waste, misinformation, and corruption.8

The method by which the Commission tries to sidestep the problems posed by centralised planning in practice is interesting but, in the end, a failure. The steps are the following. Firstly, the planners state general goals, such as those listed in Table 1. Secondly, their practical and concrete definition is passed over to the MS, which present their various national goals. As we saw in the case of Spain, the governments outline a general plan of how these goals are to be achieved in their jurisdiction. Thirdly, private firms of all sizes present their own transformation projects to their government and the Commission. Fourthly, to avoid the ‘Khrushchev mistake’ the whole process is undergirded with a ‘Performance Framework’, overseen by a ‘Recovery and Resilience Taskforce’, so as to follow and control the exact realisation of projects. All this, in a way, is an acknowledgement of the difficulty of attaining such wide-ranging goals as those financed by the RRF.

5. The Plan as politics

The Recovery Plan for Europe, as I said at the beginning of this article, is another attempt to further the integration of Europe, especially of the Eurozone. Many of the persons in charge of European institutions see as the goal of the European Union its slow transformation into a federal state. This is not the general wish of the citizens of the MS but there is no doubt that the persons employed at the Commission see this as the object of their endeavours. One could even say that a majority of the MEPs at the European Parliament are also federalists at heart.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the founding fathers of the EU, Konrad Adenauer, Alcide De Gasperi, and Robert Schuman, inspired by Jean Monnet, chose an indirect path to get the former enemies to work together in building a peaceful Europe: rather than politics, it was the economy and the Common Market that opened the way. When I say that the Commission’s Plan will further the idea of a federal Europe, I am not trying to derogate from their achievement, but I am saying that the kind of Europe the Commission’s Plan is seeking to construct is not liberal. This is not the first attempt to take a big step to federalise Europe: the constitution proposed by the committee headed by Giscard d’Estaing wrote a document that the citizens of France and the Low Countries rejected. No matter. The failed constitution was transformed into two Directives and applied surreptitiously. The Resilience and Recovery Plan is doing it again.

The authorities at the head of the EU find it impossible to conceive a Union based on free economics and open institutional competition. A Brussels Commission financed by external tariffs and mutualised debt will always choose centralisation over bottom-up spontaneity. The question I set at the beginning, whether this Plan will make Europe freer and more prosperous, must be answered with a concerned No.

References

Alonso, D., Kataryniuk,I., Moreno, C., and Perez, J.J. (2022). ‘El programa Next Generation EU. Características y claves para su éxito’. Información Comercial Española, 924, 77–98.

European Commission. (n.d.). ‘Recovery Plan for Europe’, https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/recovery-plan-europe_in Aparici Vazquez de Parga, E. (2022): ‘El Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia: Inversiones y Reformas. Información Comercial Española, January/February 2022. Number 924. Pp. 99-112.

Hayek, F. A. (ed.). (1975 [1933]). Collectivist Economic Planning: Critical Studies on the Possibilities of Socialism. New York: Augustus M. Kelley.

Hayek, F. A. (1975 [1933]). ‘The Nature and History of the Problem’.

Hayek, F. A. (1975 [1933]). ‘The Present State of the Debate’.

Mises, L. von (1975 [1933]). ‘Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth’. In F.A. Hayek (ed.), Collectivist Economic Planning: Critical Studies on the Possibilities Socialism. New York: Augustus M. Kelley. Originally published as ‘Die Wirtschaftsrechnung im socialistischen Gemeinwesen’ in 1920.

Schwartz, P. (2000). The Euro as Politics. London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

Spufford, F. (2010). Red Plenty. London: Faber and Faber.

Vazquez de Parga, E.A. (2022). ‘El Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia: Inversiones y Reformas’. Información Comercial Española, 924, 99–112.

About the author

Pedro Schwartz

Universidad Camilo José Cela

Dr Pedro Schwartz is Rafael del Pino Professor in the Department of Economics at Camilo José Cela University in Madrid. He is a Bachelor and Doctor in Laws of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, and a Master of Economics and a PhD in Political Thought at the LSE. Apart from his academic and political career, from 2006 to 2008 he was working for the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European