Introduction

The financial situation in Spain has reached its limit. The State will reduce its tax revenues due to the drastic drop in activity, so the Executive branch is searching for ways to cushion the decrease in tax collection without further stifling families and small businesses. In this context, the tax on wealth has once again risen to the surface, this time masked under the name of the COVID Rate.

Over the years, public management of the Spanish economy has brought us to a level of debt that, at the moment, is close to 100% of gross domestic product (GDP). The enormous debt resulting from the Great Recession and the sovereign debt crisis, as well as the stimuli preceded by the rescue of the country, meant an increase in Spanish public debt, which has not since lowered. In relation, this report analyses an evolution of the Spanish fiscal pressure, or how subject the Spanish are to State taxes. Despite the fact that the fiscal pressure is a relative figure on the GDP, we have observed how it has been growing progressively in Spain, from 14.3% in 1965 to 35.2%.

Thus, this indicator presents an increase of over 146%, which shows how Spaniards have borne a higher tax burden over the years. This only experienced a reduction in 2009, when collection, relative to GDP, was reduced by the effects of the Great Recession. A more appropriate indicator would be the tax wedge presented by Spain, as compared to other countries internationally. According to the report on the OECD, Spain shows a fiscal wedge of 39.4%, well above the average of the member countries which is 36.1%.

Moreover, in order to reduce expected debt concern after the pandemic dissipates, the current Government has removed heavy taxes: a cast of new taxes that seek first and foremost to raise more capital, while simultaneously increasing spending.

The Vice President of the Government, Pablo Iglesias, has thus proposed the creation of the COVID rate, the Tobin rate, the Google rate, as well as new sections in personal income tax. Taxes that are born or are modified with the intention of «making the tax system fair and progressive.” However, further observation of these taxes and the inflated party estimate in tax collection shows that while public spending is forecasted to increase by 0.5% of GDP, this supposed, based on the same program, an aggregate expenditure of 3.1% of GDP.

This collection, if fulfilled, would not even be a game of sum 0, but would perpetuate the same situation as always: raising taxes again in search of higher income while expected public spending continues to expand the level of debt, for which we must disburse more capital, including that estimated in the collection. The COVID rate plans to increase this by 11,000 million euros. On the other hand, the expenses that the State maintains, if no reforms are applied, place the deficit level of the Spanish economy, in absolute terms, at 110,000 million euros, as estimated by AIReF when deriving the aggregate effects of the health crisis.

All in all, the COVID rate is not a new concept, since, in reality, it is a modification of the existing, albeit extraordinary, Wealth Tax (IP). For this reason, it is convenient, before delving into the possible economic effects that its implementation would trigger, to know the route of this tribute in Spain, as well as its peculiarities.

The History of Wealth Tax (IP)

The Wealth Tax has its origin in Spain in 1977, specifically in Law 50/1977, of November 14, on Urgent Measures of Tax Reform which established, on an exceptional and temporary basis, an Extraordinary Wealth Tax on such persons residing throughout the Spanish territory.

Of that Law, the modification of the Luxury Tax is worth noting. According to article 79 of the Law of December 26, 1957, this tax was levied on everything that was merely decoration or enjoyment of superfluous goods. The article read as following:

«The Government is also authorised to tax, within the taxes on luxury, the acquisition or enjoyment of superfluous goods or goods that represent mere decoration, ostentation or gift, as well as services having the same character or that represent comfort higher than normal.”

In the aforementioned amendment, special taxes applied to the purchase of vehicles, boats or drinks that exceeded 80 pesetas per liter and that were not framed within the exceptions established by the Government.

The Law of 19/1991, of June 6, on the Wealth Tax, put an end to the previous one, which had a supposedly transitory nature, to comply with the memorandum of this Law, whose primary objectives were: to the additional capacity of the possession of the patrimony, to reach a more efficient use of resources, to improve the redistribution of wealth, and to complement the Personal Income Tax (IRPF), as well as the Tax on Inheritance and Donations.

The State’s eagerness to collect led it to adapt the tax to achieve precisely what they were not capable of: profiting more. However, it is worthy of mention that the explanatory statement presented in 1991 recognised that configuring a single value of assets and rights valid for the entire tax system, and at the same time ensuring the achievement of the objectives of sufficiency, equity and efficiency assigned to it, was clearly impractical, both in theory and in practice. This was mainly because each tax has a different objective, as well as the expected participation of each one in achieving the objectives mentioned in the Law.

However, they continued collecting until Law 4/2008, of December 23, when the same political party that had justified the establishment of the tribute repealed it for its marked confiscatory nature.

Executive José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, who was never accused of favouring the self-proclaimed ‘wealthy,’ recognised that these economic transformations caused the tax to lose all ability to effectively achieve the purposes for which it it was designed. In other words, it did not have the alleged effects declared in 1991.

Finally, the Royal Decree-Law 13/2011, of September 16, restored the Wealth Tax with a hypothetical temporary nature. It is a bit curious that the same justification that had served for its repeal was inverted. Thus, the Royal Decree-Law indicates that “in the configuration of these measures, which complement others already adopted, it is essential to apply the principle of equity so that there is a greater contribution towards exiting the crisis by those who have a greater economic capacity.” Justifications diametrically opposed to those offered by the same Prime Minister, Rodríguez Zapatero. The exempt limits were indeed modified: from € 108,000 to €700,000 and, in the case of habitual residence, from €150,000 to €300,000.

Several conclusions can be drawn from the above about the behavior of the rulers. They are capable of saying one thing and then the opposite in the span of only three years in order to continue raising as much money as possible. Thus they destroy the assets of those who have already paid the price of obtaining them, through other tax demands. On the other hand, it is also common for the supposed temporary nature of a measure to last longer than expected. For this reason, the taxpayer should always bear in mind that “transitory» is probably just masking a “permanent.”

Some arguments surrounding the wealth tax

Although this is not an argument in itself, it is striking that after the abolition of this tax in France in 2018, only three members of the OECD continue to implement it (Finland, Sweden and Switzerland). In other words, it is a highly unique tax in terms of advanced countries.

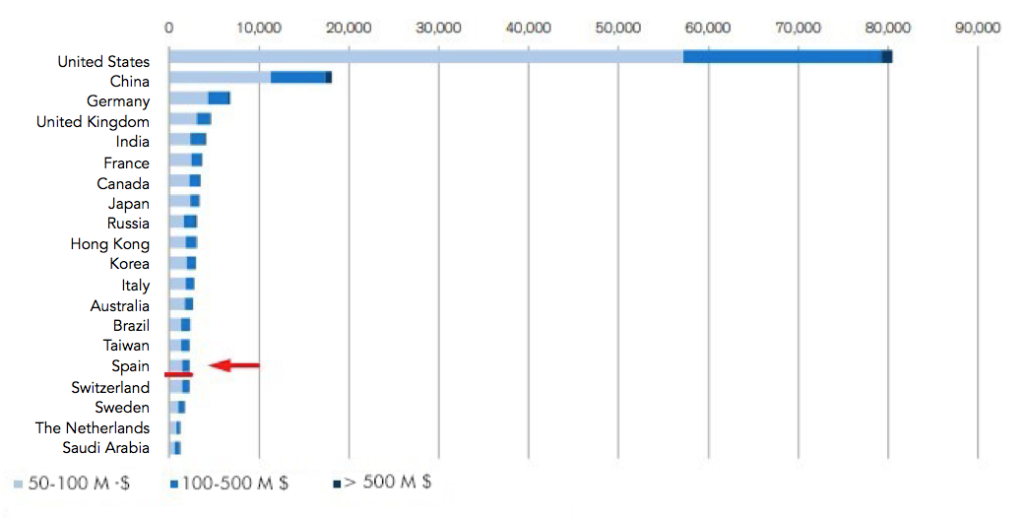

Despite this, of course, there exist positions for and against. It may be true that, as indicated by Saez and Zucman [1], certain configurations of the same supposed an increase in the collection and a redistribution of wealth. But it is no less true that, in that same study, they cite, though reluctantly, the reasons that have led all the countries of the European Union, with the exception of Spain, to eliminate it. From this study, it should also be noted that they do not pay enough attention to the specific case of Spain (except for some slight references to the erosion of the tax base), instead focusing on US billionaires. Our country barely exceeds 2,000 people with more than 50 million dollars, while the United States approaches 60,000.

Graph 1. Top 20 countires with ultra-high net worth in 2019

As we will see later with data from the Tax Agency (AEAT) on people with more than one million euros, 99% of filers stand below 100 million dollars. In Spain, there are only 61 people [2] who have a net wealth of more than 500 million dollars.

Next, we will address three of the arguments most used by those who want to establish the tax, and we will comment on them from different perspectives.

- Those who have the most must pay

According to a training led by Pablo Iglesias, those who have the most should pay the most. In other words, the “rich” must assume more taxes because they have the capacity to bear a greater tax burden.

The above, in addition to not necessarily being true for all cases and at all times, is not fair. For it to be, the COVID rate would need to be a truly progressive and non-discriminatory tax, like adaptations on the tax in Switzerland, Norway and the Netherlands. Otherwise, it discriminates simply for possession of wealth. A wealths for which taxes have already been paid, although advocates argue that this tax demand intends to complement what income taxes are not capable of taxing [3].

Furthermore, it is argued that possession of the estate could be additional enjoyment, which is true. But it is also true that, to have wealth, one must first create it, usually by founding companies which then generate benefits, with associated risks that many are not willing to face. Something perfectly legal but that does not justify in any way that the one who has more, simply for that fact, pays more. This is especially true when the wealthy are likely to consume the least public services, from healthcare to education. That is to say, although sponsors pay the equivalent to many taxpayers, this is not why the Public Administrations reward them with greater rights.

In addition to greater risk taking, generating wealth also leads to a reduction in present consumption by virtue of the future. That is, when we save, we are sacrificing spending today for potential spending tomorrow. What incentive will someone have to save when they know that, after a certain limit, their capital will begin to decrease? It is, therefore, an incentive to spend, which is entirely contrary to what, according to De Nardi [4], constitutes an entrepreneur without initial assets: a higher rate of saving than the households that are in a similar situation in terms of income.

Without savings, one cannot make large investments in the future, and is limited to continue working with the same means of production and without making progress. Although saving does not necessarily generate investment, it does precede it, and this increases the income generated — not only by the wealthy, but by the entire population. Therefore, we need incentives to save and invest, not an additional expense whose sole purpose is to prevent the State from taking what belongs to you. Beyond the fictitious creation of bank money, a minimum of people must be saving to be able to lend and equilibrate accounts.

Another argument in favour of the tax is that, according to a survey by the University of Chicago, inequality can pose a threat to liberal democracies [5] [6]. Historically, this has been the case, and has consequently generated significant political polarisations. But, taking into account the classic indicators of inequality, nothing indicates that the wealth tax contributes to reducing it. With a suitable configuration for each frame, it would be at best another piece of the board.

As we stated at the beginning, it is not necessarily true that the wealth implies a greater ability to pay, since these estates invest, move their money, conduct businesses projects, and increase the capital of their companies. Furthermore, their investments do not remain immune to economic fluctuations, and these affect them equally despite greater wealth.

As if that were not enough, the tax does not fall only on those with a relatively greater capacity, but also on those who, with above-average wealth, are still far from the truly wealthy. In fact, one of the reasons why the IP was abolished in 2008 was precisely because it was supported by the middle classes since at that time, the exempt minimums were much lower.

- Taxing wealth causes efficient use of capital

From the point of view of efficiency, the main argument focuses on the fact that IP does not necessarily encourage spending, but rather to make productive investments. Of course, efficiency is questioned when one must search for these investments (and find them) almost every year.

Businesses and investments do not follow calendar years, so forcing them to be carried out could turn out to be highly inefficient. In fact, the speed of tax pressure can motivate less productive investments to be made. There are models [7] that, at a theoretical level, try to justify that IP promotes efficiency; more practical ones argue that it must exist for horizontal equity, and to tax unobserved capital income (already cited above) [8].

However, this all seems to indicate, albeit indirectly, that wealth is only capable of seeking profitable investments if this tax exists. This is false; if this were the case, we could simply establish a very high COVID Rate to promote the productive use of capital. Any academic would affirm that there is an optimal point at which the marginal returns obtained after in terms of tax collection would become, causing an inefficient allocation of capital.

It is also not efficient from the point of view of attracting capital, since nobody takes their money to a country that will charge a tax. Thus, Spain will not be a preference for large foreign capital. What’s more, it will force those already settled here to look for legal formulas (because they exist) to place their heritage outside our borders. Although, given the argument of efficiency, perhaps some naive persons still believe that those with great fortunes will prefer to go to a place where they tax their wealth in order to encourage the efficient use of their own capital.

The misnamed rich have the economic capacity to move this capital, or invest it in other countries that stimulate the generation of wealth. To think that this is not possible is absurd’ even more so is to believe that the only way to avoid paying the tax is to leave the country. One of the problems that legislators have encountered (and will continue to encounter) is that there are legal formulas for holding assets in companies. It is not even necessary to resort to the big companies: many people with much more modest assets take advantage of legal entities to avoid payment.

Along these lines, Durán-Cabre, Esteller-Moré and Mas-Montserrat [9] demonstrated that in the case of Catalonia, the declarants did indeed react to the tribute, both in terms of re-organisation of its assets and mobility. This same working document concludes that, in this case study, an average increase of 0.1% in the tax translates into a reduction of the tax base of 3.24%. In other words, increasing the IP increases the probability that taxpayers decide to pay less.

- We have to control the rich

This last point is about control of the wealthy. According to tax advocates, the COVID rate would complement personal income tax. That is, it is based on the presumption that large estates do not declare everything they should, and that this concealment of income would be balanced by a tax. With this tax, by the way, their assets are supervised and located so that they cannot make decisions that allow them to pay less. Such action is typical of a collecting State that constantly seeks to exercise dominion over the lives of citizens, their possessions and, ultimately, their future.

Moreover, this attack on freedom implies inability to depart from the system, which none of the aforementioned documents address. They all focus on real or theoretical models, but none stops to sufficiently unravel the issue of the real reduction of freedoms. And yet, the COVID rate is equivalent to a barrier to investment. It leaves out any option of not wanting to produce. This contrasts with the ideals of the party that intends to implement it. Unidas Podemos, against the market, directly and indirectly obliges investment/production. In this framework, it is not possible to save in order to not work and dedicate oneself to what he wants, since, if one so chooses, they will suffer the relentless effects of inflation in addition to a tax that, over the years, will end up confiscating all capital.

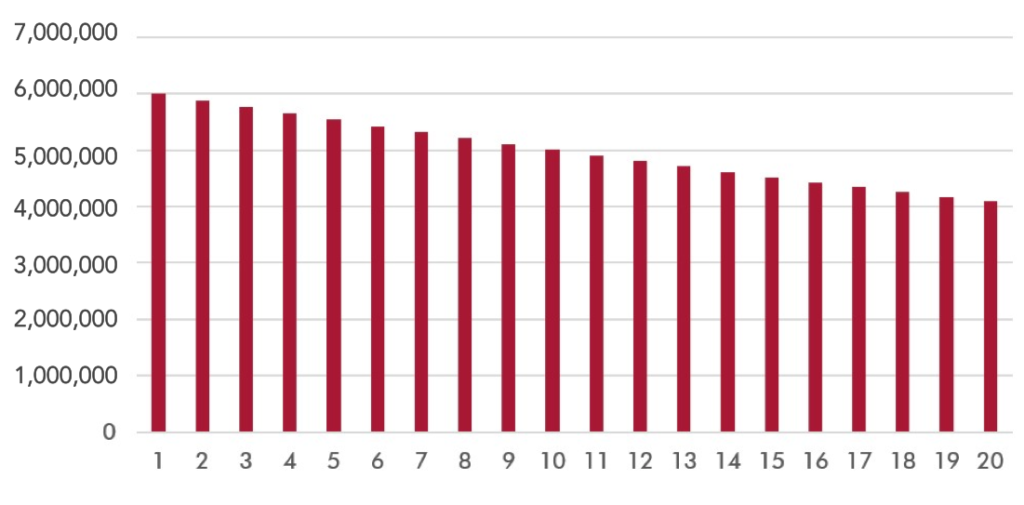

Thus, a person with 6 million euros who decides to keep them in a current account and not invest them, without taking inflation into account, will experience a reduction of 33%. If an average inflation of 2% is taken into account, the decrease in purchasing power would shoot up to 55%. Simply for doing absolutely nothing.

Graph 2. Reduction of capital derived from the Covid rate

Surely, some might believe that the rich man, 20 years later, will continue to enjoy a purchasing power of 40 million euros. But this argument denotes very little respect for private property. Regardless of its amount, any act that works against it continues to be serious in the same measure.

Not to mention the difficulty of establishing (and studying) a tax that is levied in an “adequate” manner and equally on different estates; various aspects must be considered such as wealth at market prices, the heterogeneous configurations of the tax between autonomous communities, or the difficulty of valuing certain assets constitute obstacles that legislators recognized in 1991.

Wealth Tax Collection

Until now, the theoretical aspect of the tax has been addressed, for which some may be in favour and others in opposition, or on which there may be some empirical evidence. In this argument, several studies try to support data on for either side. However, there is a point on which both detractors, and those who support it agree: the effective collection of the current IP.

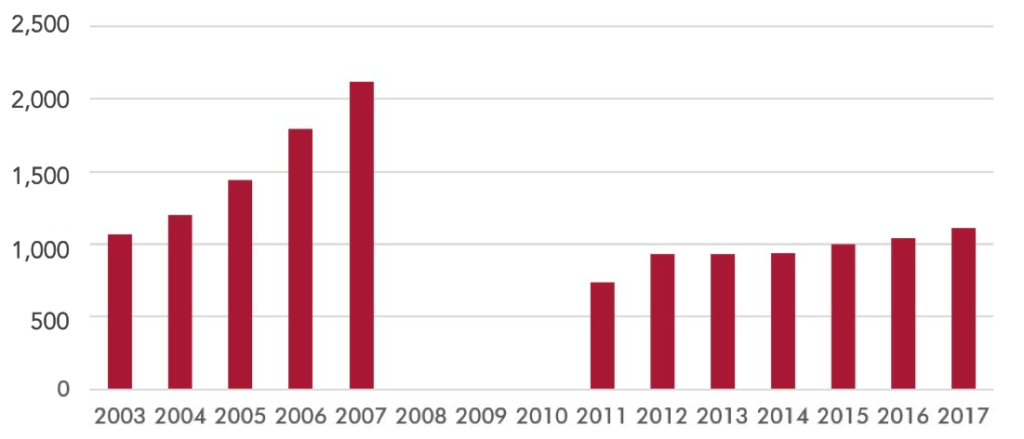

Graph 3. Levy tax on the wealthy in millions of euros

In light of the data, this has been extremely rare. In 2017, it only represented 0.57% of total tax revenue. If we consider total public revenue, the figure drops to a negligible 0.23%.

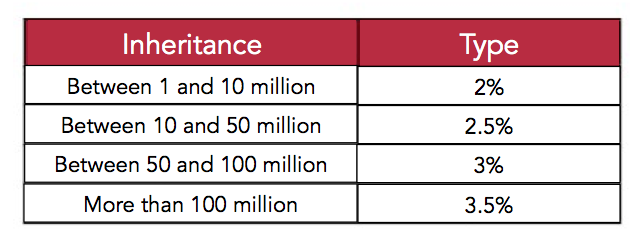

However, suppose that, in effect, the changes proposed by Unidas Podemos are carried out, proposing to reach up to 11,000 million; that is, multiply the current collection by ten. The types that this understanding raises are the following:

Table 1.

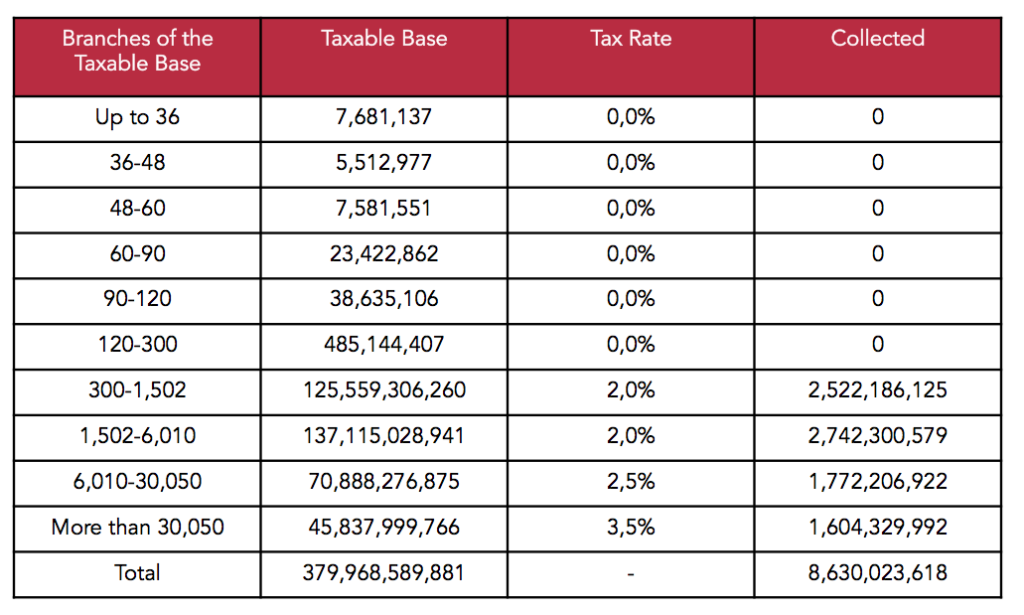

Without losing sight of this, we should keep in mind the data provided by the Tributary Agency of 2017 (last update available).

Table 2.

As dictated by the Wealth Tax Law, the tax base is the net worth of the taxpayer. That is, the value of the goods which he owns, determined in accordance with the rules of the articles cited in the Law, subtracted by the charges of their nature; when the value of these goods or rights decreases, the personal debts or obligations to which the taxable person must respond. In simpler words, what you have minus what you owe for what you have.

Thus, without taking into account the progressiveness of the tax, or exemptions of any kind, nor that those who are below the tranche between 120,000-300,000 euros will not really be taxed, and being benevolent in the tranches when applying the rate of tax, the maximum collection that would be obtained would be, in the most optimistic scenario, of about 8,630 million. In other words, 2.4 billion less than budgeted.

And all of the above still exists under the assumption that all assets located in Spain would continue to be taxed in the same way, and that they would not experience any loss derived from COVID-19. This factor its especially important, considering that the distribution of assets reflects that approximately 20% are in Collective Investment Institutions, which have suffered the largest drop in history since the World War II.

Therefore, the United Nations tax collection estimate is not only extraordinarily inflated, but could also lead to the outflow of capital from Spain, which would further aggravate the situation.

This tax will not be paid by the ultra-rich

Spain, unfortunately, does not stand out because its population includes many of what Americans know as billionaires. The data in the previous table, referring to the 2017 financial year, indicates that 70% of what is declared as a tax base is concentrated in assets of less than 6 million euros. Although in our country this figure is seen as something extraordinary, it is not unreasonable that a person has 6 million euros after having worked and invested wisely throughout his life.

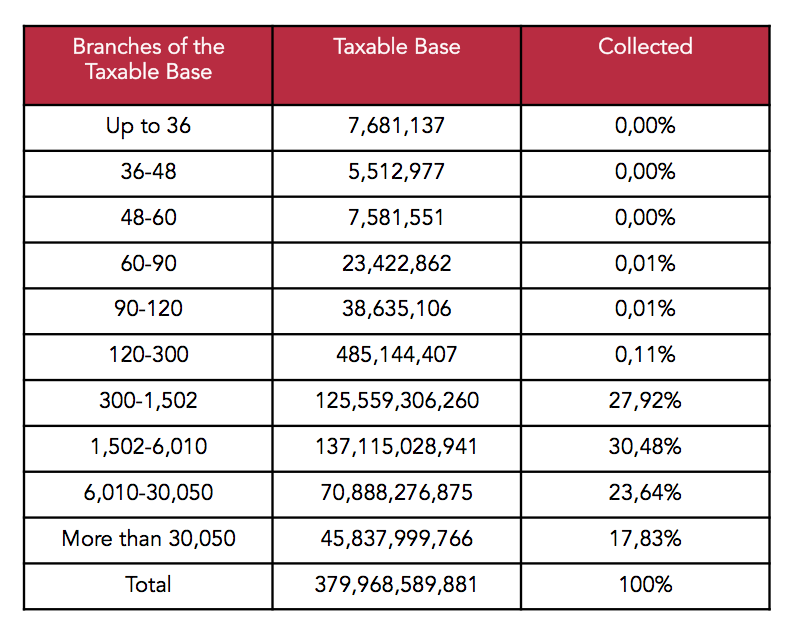

Table 3.

If we attend to the quota satisfied by our inflated and optimistic estimates, with the distribution relative to 2017, taxpayers with a capital of less than 2.5 million euros would be paying 28% of everything collected by the State due to this tax.

From another perspective, with the tax base again as a reference, if the State imposed not 3.5%, but 10% on those ultra-wealthy with more than 45,000 million in assets, the collection would amount to 4,500 million. All this avoids the reduction of wealth due to the current crisis or the possible movements that they would do to avoid the payment.

In conclusion, beyond the estimates, those who will actually satisfy this tax will be those with assets of less than 6 million euros, which account for 70% of the entire IP tax base. These assets, however high they may seem, are far from the perceptions of those who believe that this tax will only be paid by the ultra-wealthy.

[1] Saez, E. y Zucman, G., (2019). Progressive Wealth Taxation.

[2] Credit Suisse, (2019). Global Wealth Report 2019.

[3] Piketty, T., Saez, E. y Zucman, G., (2013). Rethinking Capital And Wealth Taxation.

[4] De Nardi, M. y Fella, G., (20179. Saving and wealth inequality. Review of Economic Dynamics, (26), pp. 280-300.

[5] Igmchicago.org, (2020). IGM Forum. Retrieved from http://www.igmchicago.org/surveys/inequality-populism-and-redistribution-2 .

[6] Winkler, H., (2019). The effect of income inequality on political polarization: Evidence from European regions, 2002–2014. Economics & Politics, 2(31), pp. 137-162.

[7] Guvenen, F., Kambourov, G., Kuruscu, B., Ocampo-Diaz, S. y Chen, D., (2019). Use It Or Lose It: Efficiency Gains From Wealth Taxation. NBER Working Paper. Nº 26284.

[8] Díaz, A., y Puch L., (2020). ¿Por Qué Gravar La Riqueza? (III): Mitos, Leyendas Y Realidades. Nada es Gratis. Retrieved from https://nadaesgratis.es/luis-puch/por-que-gravar-la-riqueza-iii-mitos-leyendas-y-realidades

[9] Durán-Cabré, J.M., Esteller-Moré, A. y Mas-Montserrat, M., (2019). Behavioural Respones To The (Re)Introduction of Wealth Taxes. Evidence from Spain. IEB Working Paper. 2019/04