Main conclusions

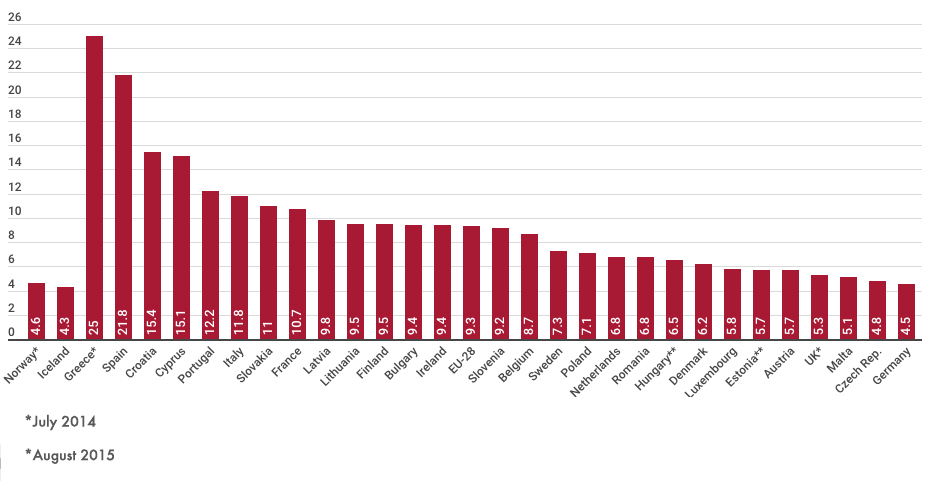

(i) Spain is, together with Greece, the EU country with the highest unemployment rate

(ii) In both Greece and Spain, average incomes pay higher labour taxes than other EU-15 countries

(iii) Social Security contributions are the largest labour tax

(iv) The employer’s social security contribution amounts to more than 50% of the set of labour taxes. From this point of view, Spain is the second country in Europe with the highest tax opacity

(v) Due to Social Security contributions, labour taxation is regressive for certain income segments

(vi) Spain is the second country with the highest prices in Europe. To benefit from the public pension system, the Spanish worker contributes 6 points more to Social Security than the EU-15 average. Overall, Social Security has an extra cost of 8 percentage points above the EU-15 average.

(vii) Spain is an exception within the EU countries since it is mandatory to pay a minimum Social Security contribution, while it is common to have a minimum exempt base.

Analysis

With a 21.8 percent of unemployment rate, Spain remains the second country in the European Union with the highest level of unemployment. Currently only Greece has a labour market that works worse than ours. Moreover, Cyprus and Croatia, in third and fourth position, follow us, but with an abysmal difference: their unemployment rate is around 15 percent; a level that Spain aspires to reach in 2018, although the forecasts seem today too optimistic .

Graph 1. Unemployment rate in the European Union (Sep. 2015)

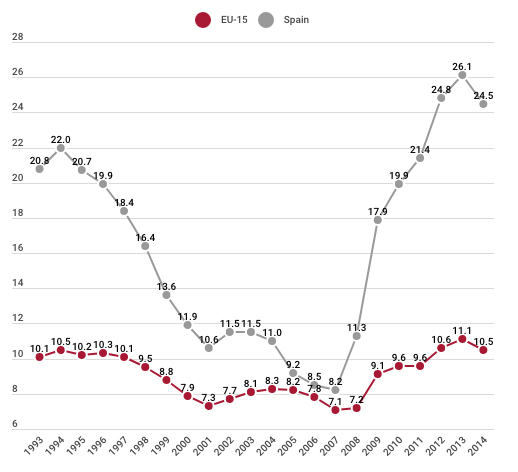

At first glance, unemployment seems to be a consequence of the crisis, of the economic cycle or a problem of job offer. However, unemployment is not a problem linked today to the economic crisis, but to the fact that Spain has always had an unemployment rate above the European average.

Graph 2. Unemployment rate in Spain and EU-15

A report from the European Commission (Taxation Paper No. 56, European Commission, 2015) reveals that in Spain the taxes on labour are excessive, especially Social Security contributions. Therefore, the study recommends reducing labour taxes and especially Social Security contributions to reduce unemployment and activate consumption.

Labour taxation in Spain. Excessive taxes?

Salaries in Spain are triple taxed with Income Tax, Social Security paid by the worker and Social Security paid by the employer. Most developed countries apply a progressive income tax, which means that people with higher incomes pay a higher percentage of taxes and people with lower incomes pay a much lower percentage.

However, income tax and social security contributions are an important source of income for the State. Therefore, in many countries middle-class workers endure a high tax effort. Although these taxes and especially social security contributions fund pensions and other services, it is important to know the cost of these programs for the average worker.

According to the latest report of the Tax Freedom Day 2015, which analyses the taxation of labour in Spain, the tax rate applied in our country is 40.7 percent on an net income of 1,679 euros, similar to that applied in countries such as Sweden or Finland. However, a crucial difference should be noted: the average salary of these countries is 70 percent higher than the income of a Spanish worker.

Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway or Ireland are other countries that, with much higher income levels than the Spanish, tax salaries at much lower tax rates than ours: between 28 percent and 38 percent, respectively. Therefore, the tax effort of the average Spanish worker is higher than that of the rest of the workers in Europe, setting Spain, together with Greece outside the range of progressiveness delimited by the rest of European countries. In fact, as shown in Graph 1, the unemployment rate in Spain and Greece is way different to that of the rest of Europe.

Graph 3. Labour taxation in Europe (2015)

Regressiveness

To determine the tax effort based on income, eight levels of income have been analysed. For each income, the labour cost for the company and the real tax rate have been calculated taking into account the Income Tax and Social Security contributions borne by the employer and the worker.

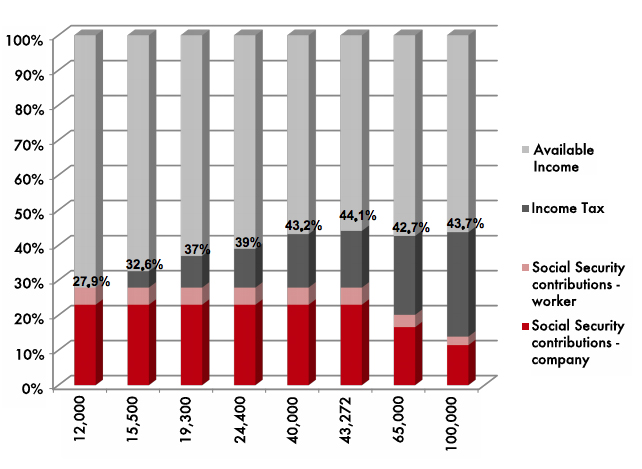

Graph 4. Real tax rate according to income level

As we observe, the real tax rate reflects great progressiveness in the first levels of income, rising from 27.9 percent for a worker who does not reach one thousand euros per month to 44.1 percent for a gross annual salary of 43,000 euros. From this level, the real tax rate is regressive: so that the rate goes down to 42.69 percent for a gross salary of 65,000 euros per year, and goes back up to 43.74 percent for a gross salary of 100,000 euros.

The latest OECD report, Taxing Wages 2015, also highlights that Spain is one of the countries with the highest progressiveness in the first three levels of income and reduced progressiveness for higher incomes.

Understanding how the progressiveness/regressiveness of the tax system works is key to understanding the unemployment rate. A report from the European Commission (Taxation Paper No 56., European Commission 2015) that analyses the effect of the tax system on the labour market in Spain, Italy and Austria finds a positive relationship between lower labour tax progressiveness and higher unemployment levels.

This behaviour of the real tax rate is largely due to the design of social security contributions, which reduce progressively the income tax. In addition, social security contributions in Spain are not only characterised by low progressiveness, but also strongly regressive: the more one makes, the less one contributes.

Social Security contributions

Social Security contributions have a single tax rate in Spain. It is not a progressive tax like personal income tax. In addition, no deductions are made depending on the level of income. Therefore, even for the lowest income, the rate applied is the maximum, of 36.25 percent: 29.9 percent paid by the company and 6.35 percent by the worker.

However, the contributions have a maximum limit: gross income that exceeds 3,606 euros per month (43,272 euros per year) only pay up to this level, so that no taxpayer can contribute more than 15,686 euros per year to Social Security. Consequently, higher incomes benefit from this system, since although the Income Tax is still paid, as a whole, the real tax rate is reduced for certain income segments.

The Welfare State has always defended a greater weight of the Income Tax in the fiscal mix due to its progressive nature and its high redistributive power. However, the data show just the opposite: sometimes it is more common for the VAT or Social Security contributions (non-progressive taxes, sometimes even regressive) to have more weight in the tax system than Income Tax. In Spain, most of the total collection, 35 percent, is obtained via Social Security contributions.

But we are not the only OECD countries where Social Security has such weight in the collection of the State. This also occurs in France, Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Slovenia. However, there is also a large number of countries such as Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, Portugal, Estonia, Hungary or Chile where the income tax or the VAT have a greater weight than Social Security contributions.

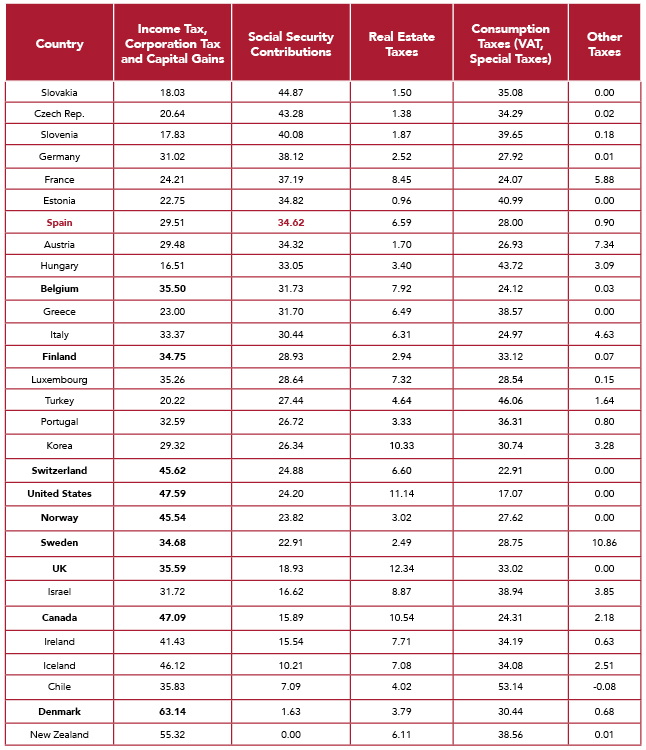

Table 1 Tax collection by source of income (%) in OECD countries (2013)

Tax opacity

Of labour taxes, the personal income tax is only one part of the taxes borne by labour. As it has been seen, to determine the exact amount of taxes that a worker pays, it is necessary to add the Social Security contributions to the income tax. Although it does not seem like a difficult exercise, it is nevertheless an obstacle in order to create a clear and transparent tax system.

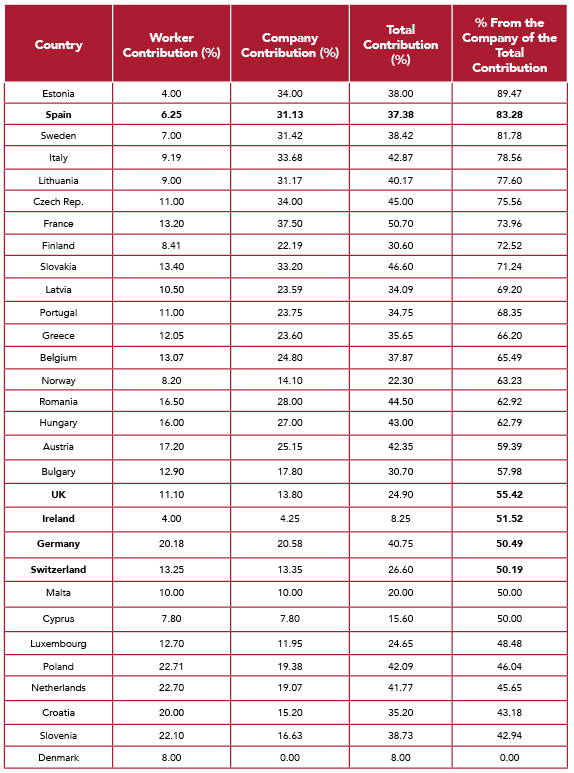

Table 2. The Weight of the Employer’s Contribution to Social Security

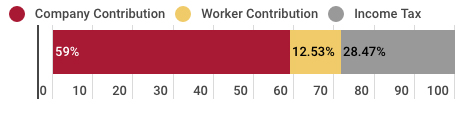

Nevertheless, what makes the tax system really opaque are the Social Security contributions, which the employer has to pay and that are not included in the gross salary of the worker. Moreover, these contributions represent more than 50 percent of the taxes on income paid by an average salary worker.

Graph 5. Weight of each tax in the total tax burden

This way, the worker does not know the exact amount of taxes he bears, since part of his income is disguised as an amount paid by the employer for business benefits. Although Social Security contributions are the main source of income of the Spanish State, taxpayers are not aware of this weight because most of these contributions fall on companies.

In Spain, the employer’s contribution to Social Security amounts to 83.28 percent of the total contribution. Estonia is the only country in Europe that manages to exceed this percentage. In contrast, in countries such as Germany, the United Kingdom or Ireland, contributions are made in equal parts, making the system much more transparent.

Who pays social security contributions?

The worker’s contribution to Social Security is directly withheld from his gross salary. However, the question is: who supports the contribution paid by the employer above the gross salary of the worker? The economic literature has not reached a consensus on the exact percentage of the social security employer’s contribution that falls on workers. However, there is a clear acceptance that all or almost all the weight is borne by workers in the form of lower wages, higher prices and higher unemployment.

When analysing social security contributions in the US, Brittain found results “consistent with the hypothesis that 100 percent of the tax falls on labor.” Gruber analyses the results after a “lower income tax on the Chilean workers ”and estimated that“ the incidence of taxes falls on wages, with no effect on employment ”. Because the labour market is more rigid than the market for goods and services, the tax burden does not fall on consumers through higher prices of goods and services, nor on capital, through the reduction of benefits, but it is supported by workers through lower wages.

However, certain groups of workers simply cannot accept lower incomes because of social security contributions. For them, the cost in terms of time and effort exceeds the economic benefits of having a job. For this group, social security contributions make the difference between having a job and being unemployed.

Social security contributions are responsible for the difference between the value generated by the worker for the company and the compensation he receives. This difference creates the perception that employers obtain greater benefits from what they actually achieve and may lead to the belief that profitability is not due to the efficiency and success of the company, but is the result of it paying its workers poorly .

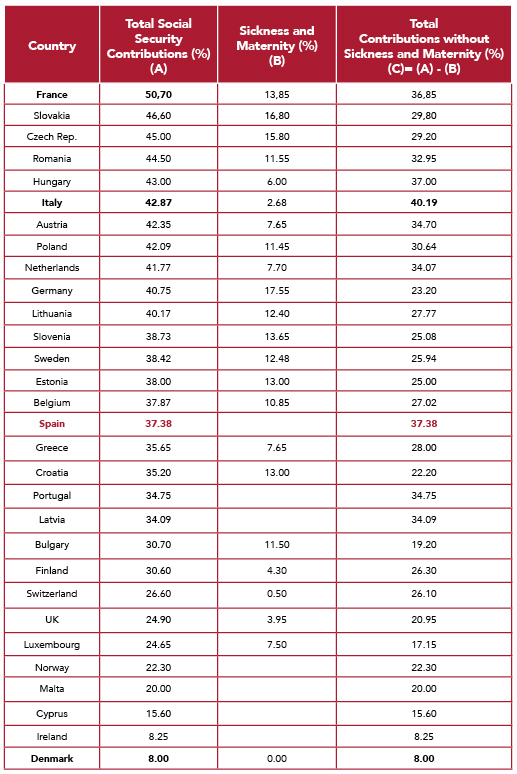

If we consider the set of social security contributions as a whole, Spain is the 16th EU-28 country with the highest contributions. This position seems advantageous, but we must not forget that most of the EU-28 countries include in their social security contributions an important contribution to sickness and maternity. However, if we deduct the contributions that the other countries make for sickness and maternity, Spain is the country with the highest social security contributions in Europe (see Table 3, column C), only behind Italy.

The reason why thirteen of the fifteen countries that apparently pay more social security contributions than Spain is that public healthcare is funded through the Social Security; hence the prices in these countries are higher. The only countries that fund their healthcare through taxes, as happens in Spain, and that contribute slightly more than Spain to Social Security, are Italy and Sweden, where public healthcare is funded through general and local taxes (Health systems from EU countries, 2013).

Table 3. Type of Social Security contribution for sickness and maternity and total contributions

How is public healthcare funded in Spain?

In 1986, the General Healthcare Law was approved in Spain and it recognised the constitutional right to free healthcare to all citizens and foreigners residing in Spain. However, the universal right to public healthcare was gradually implemented to avoid sudden growth in public health spending. In addition, the universalisation of healthcare also meant extending it to financing to avoid “the asymmetry of financing with professional sources assistance benefits” (Cabases, 1991).

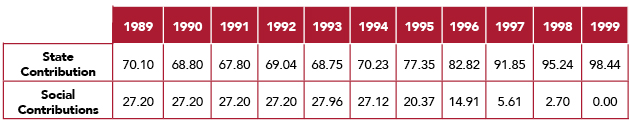

Hence, healthcare began to be funded through the General State Budgets. In 1989, only 27 percent of the funding came from Social Security contributions. In 1991, the “Report and Recommendations of the Analysis and Evaluation Commission of the National Health System” (known as the April Report) was presented, and it considered that the General Budgets should be the main source of funding of the healthcare system. But, at the same time, the report recommended to maintain the level of Social Security contributions so that individuals are aware of the cost of public services. However, since 1999, the National Health System has been completely separated from Social Security and it is now funded through direct and indirect taxes from the Autonomous Communities, as well as transfers from the State to the Autonomous Communities.

Table 4. Sources of healthcare funding (%)

Spain is the sixth country in the European Union with the highest retirement contributions, only behind Hungary, Portugal, Latvia, Italy and Romania. With 28.3 percent of the contributions going to contributory pensions, Spaniards pay 3.6 percent more than in France, 5.6 percent than in Sweden, 7.4 percent than in the United Kingdom and 9.4 percent than in Germany. Moreover, EU-15 countries pay an average of 22.45 percent for retirement, disability and widowhood. Therefore, retirement, disability and widowhood have an extra cost for Spaniards of 6 percent above the EU-15 average.

For an average gross income of 24,400 euros per year, this extra 6 percent translate into an extra cost of 119 euros per month or 1,428 euros per year. If this annual amount is put in a bank account with an annual interest of 2 percent, at the age of retirement this person would have 94,030 euros, above the public pension to which he was already entitled.

On the other hand, for a person who receives the minimum salary of 750 euros per month, the annual extra cost would be equivalent to 531 euros or 44.27 euros per month. In the same way, that amount of extra money, if saved, would translate, at the retirement age, into 34,965 euros.

Table 5. Type of Social Security contribution for retirement, disability and widowhood

Unemployment

Another important concept for which Social Security contributions are paid is unemployment. With 7.10 percent of contribution, Spain is the third country in Europe with the highest unemployment contributions, behind the Netherlands and Denmark. Given that the EU-15 average is 4.78 percent, it can be said that the cost overrun of unemployment in Spain is 2.3 percentage points.

Table 6. Type of Social Security contribution for unemployment

Therefore, in Spain we are contributing 8 percent above the EU-15 average in contributions to pensions and unemployment programs. In Spain, as in other OECD and EU countries, workers contribute to the Social Security according to the group to which they belong. As a general rule, two categories can be distinguished: workers and self-employed workers.

a) The cost of being self-employed

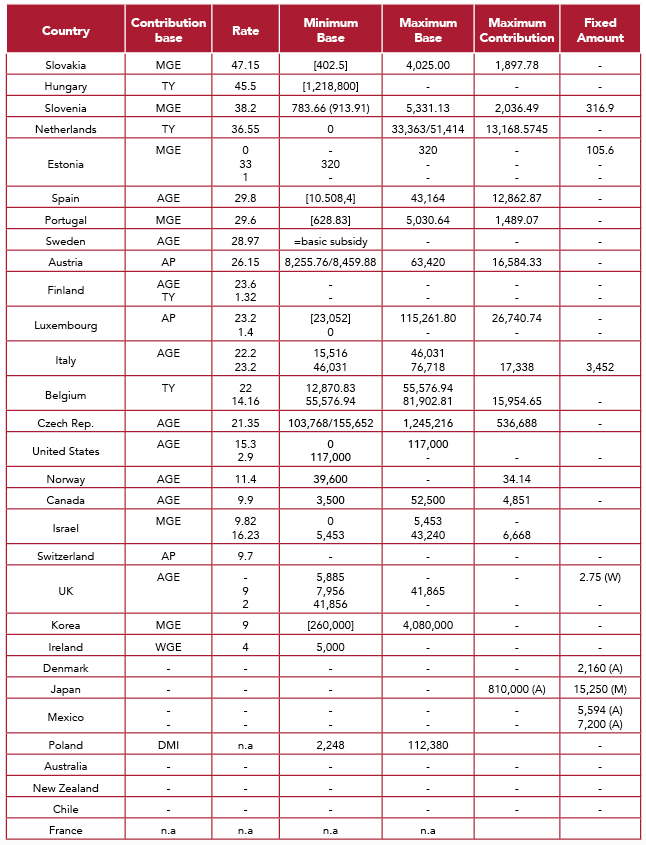

In Spain, self-employed contribute almost as much as employed workers. The contribution of the self-employed person to Social Security is a fixed percentage and not progressive as in the case of income tax. Spain is the sixth country in the OECD where self-employed workers contribute the most: 29.8 percent, only behind Slovakia (47.15 percent), Hungary (45.5 percent), Slovenia (38.2 percent), Netherlands (36.5 percent) and Estonia (33 percent). However, both in Slovenia and in Estonia, there are minimum incomes that, if not exceeded, cause the self-employed person to not pay Social Security contributions. The minimum exempt is common in many other countries, such as Belgium, Sweden, Canada, Austria, Czech Republic, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Poland and the United Kingdom.

At the other side are Spain, Slovakia, Hungary, Korea, Luxembourg and Portugal, where self-employed workers, regardless of whether they earn any money, they are required to contribute to Social Security for a minimum wage. A third model is applied in countries such as the Netherlands, Finland, the United States and Switzerland, where there is no minimum exempt, but there is taxation from the first coin made. However, this system allows to maintain a proportionality between contributions and money made and, unlike the Spanish model, it does not create an entry barrier for the self-employed with low incomes.

For example, in Finland, with a social security contribution rate of 23.6 percent, a self-employed person should contribute: (i) 11.8 euros for income of 50 euros; (ii) 23.6 euros for 100 euros of income; (iii) 118 euros for income of 500 euros; (iv) 209 euros for income of 884 euros. On the other hand, in Spain an self-employed person has to pay 263.6 euros to Social Security regardless of whether he has charged 884 euros, 50 or nothing.

Table 7. Social Security contributions in OECD countries. Self-employed

Social Security Systems around the Globe, PWC (2014)

* Note: Until recently, German self-employed were not required to contribute to Social Security. However, since January 2009, all German residents are required to have health insurance. In addition, certain groups of workers, such as those belonging to liberal professions, are obliged to contribute to a pension plan depending on the sector to which their profession belongs.

b) Employees

In the case of employed workers, apart from Spain, only Turkey and Slovakia have the obligation to pay a minimum contribution to Social Security regardless of income level. In contrast, the rest of the OECD countries pay to the Social Security system a proportional part of their income or have a minimum exempt.

However, it is worth noting the United Kingdom model, where there is also a minimum income that is exempt from contributing to Social Security: (i) Social Security contributions are not paid on the first 7,755 pounds per year; (ii) from this level, the Social Security contribution by the company is 13.8 percent without any upper limit; (iii) between 7,755 and 41,450 pounds per year, the worker’s contribution is 12 percent; (iv) exceeded the limit of 41,450 pounds, the worker’s contribution drops to 2 percent, with no maximum limit.

Conclusions and recommendations

Spain is, together with Greece, the EU country with the highest unemployment rate. However, unemployment in our country has always been higher than the European average. A report by the European Commission indicates that high rates of labor and reduced progressiveness are a possible cause of such high unemployment rate.

When analysing the taxation of labour, the study reveals that the tax effort of the average Spanish worker is superior to that of the rest of workers in Europe, setting Spain, together with Greece, an isolated examples, outside the fringe of progressiveness delimited by the rest of the EU countries. In addition, due to Social Security contributions, labour taxation is regressive for certain income segments. Although Social Security contributions are the highest labour tax, employees do not know its weight in the total taxation, since most of these contributions are paid by the employer. From this point of view, Spain is the second country in Europe with the highest tax opacity. Our country is also characterised by having Social Security contributions that are 8 percent above the EU-15 average, due to the extra cost of pensions and unemployment. In addition, Spain is an exception within the EU countries, since it is mandatory to pay a minimum contribution to Social Security, regardless of whether workers have income or not. On the other hand, other countries have opted to apply a totally opposite policy, establishing minimum bases, exempt from paying Social Security contributions. The economic literature agrees that the weight of the employer’s contribution to Social Security is borne by workers in the form of lower wages and higher unemployment. In addition, as the type of Social Security contribution is the same even for the lowest income, this fact contributes to keep the least qualified or low productivity workers out of the labour market. Therefore, to improve how the labour market operates, it is necessary to reduce unemployment and increase the participation in the labour market of less qualified workers.

(i) Include the social security employer’s contribution in the gross salary of the worker, improving the transparency of the tax system.

(ii) Introduce a minimum exempt base in Social Security contributions, as is the case with the income tax and, therefore, eliminate the minimum contribution.

(iii) Reduce Social Security contributions by 8 percent to match those of the EU-15. This way, the disposable income is increased, giving the worker greater freedom of choice, and enabling him to use that extra income to complete his public pension.

References

Berechet C. (2015), ‘Tax Freedom Day 2015’, Civismo

Brittain, J. A.(1972), ‘The Incidence of Social Security Payroll Taxes’, American Economic Review

Cabasés, J. M. (1991), ‘Reforma sanitaria, financiación y política de salud’. Economistas, diciembre/ enero, 52 European Commission (2015), ‘Study on the effects and incidence of labour taxation’, Taxation Paper No 56.

Gruber, J.(1997), ‘The Incidence of Payroll Taxation: Evidence from Chile’, Journal of Labour Economics, p. 15.

Ministerio de Sanidad (2013), ‘Los Sistemas Sanitarios en los Países de la UE: características e indicadores de salud, 2013’, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad

Molina Garrido Mª C. (2004), ’Análisis del Proceso de Descentralización de la Asistencia Sanitaria a las Comunidades Autónomas de Régimen Común: Implicaciones del Nuevo Modelo de Financiación Autonómica’, Instituto de Estudios Fiscales

OECD (2015), ‘Taxing wages 2015’, OECD Publishing.

PWC (2014), ‘Social Security Systems around the Globe’

Social Security Administration (2014), ‘Social Security Programs Throughout the World: Europe, 2014’ SSA Publication No. 13-11801, Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics