Precariousness, poor workers and temporariness. These are the terms by which the Spanish labour market is recurrently defined. One with obvious dysfunctions that have led to an average unemployment rate of 16.32% in the last 18 years. Even more dramatic figures, if possible, when we analyse the unemployment data since 2002 among those under 25 years of age, who register an average of 35.14%, and who, in the best quarter of the series, did not fall below 18%.

To this, we have to add a relatively low level of pay compared to our closest European partners. This prevents, or delays at best, the emancipation of young people, and boycotts the capacity for saving that would allow the family economy to be capitalised.

As a solution to this problem, the increase in the minimum price of the labour force has been proposed from certain quarters: the Minimum Interprofessional Wage (MIS).

At the end of 2018, with the entry of the new Executive in office, led by Pedro Sánchez, an increase of 22.3% was agreed, to which, subsequently, another 5.56% has been added for the current year, making a total of 950 euros per month in 14 payments, or what is the same, 1,108.33 euros per month if the calculation were annual.

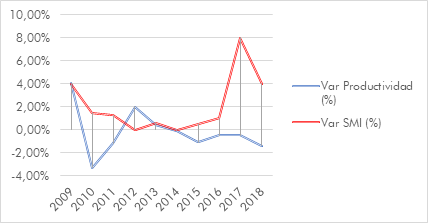

Since the outbreak of the great recession of 2008, the MIS has risen by 58%, a figure that contrasts sharply with the socialist theses of widespread impoverishment of the working class. In fact, this increase exceeds the demands of the most interventionist positions of the labour market that demand to update this minimum price with the CPI. An income of 600 euros in January 2008 (the amount of the minimum wage in that year) would be equivalent to 681.60 euros in 2019, if it had been updated only in line with inflation.

The MIS is not a reactivating element of the economy in the slowdown phase of the expansionary cycle

Despite the sustained growth over the last decade, the latest salary increases by decree have been criticized by representatives of all economic agents, mainly for two reasons.

Firstly, the 22% increase lacks progressiveness, a vital element in this type of policy in order to ensure a reduced impact on employment. Secondly, it occurs in a scenario of uncertainty and economic slowdown.

Wage trends must be in line with employee productivity per hour worked and with current macroeconomic expectations.

Over the past few years, although it has developed unevenly, economic growth has served to cushion the negative impact on the labour market.

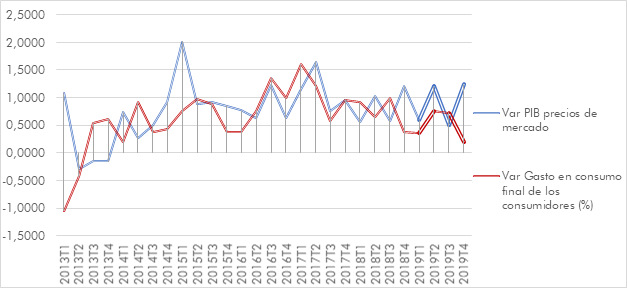

However, the promoters of the increase in the MIS argue that this measure serves as a reactivating element of the economy: that is, theoretically, the wage expansions of low incomes will have a positive impact, since they will consume more, which, in turn, will be reflected in an increase in GDP.

This thesis, although it may be partially true, has no economic validity. A country’s GDP is composed of more elements: investment, net exports, and public spending. Even assuming increases in consumption and public spending, as stated in the Government’s Agenda, growth can be hampered by losses in exports and investment.

It should not come as a surprise that investment is being cut back as a result of the measures proposed by the current government, such as the tax on financial transactions, higher tax rates, barriers to innovation, the relocation of innovation via the «Google Tax» and a deterioration in public accounts, whose deficit targets are tending to be «relaxed».

Similarly, the current global trade tensions, the negative effects of the coronavirus on the Chinese economy, lower growth in the euro area, and the recovery of tourism alternatives in the African Mediterranean could reduce net exports.

In any case, far from accepting as a tautology the increase in consumption as a result of a previous SMI, we should question and contrast it, especially when it has been implemented as a «reactivating» measure at times of slowdown in the expansive economic cycle.

It can be seen that, after the disproportionate increase in the MIS in 2019, household final consumption expenditure has experienced a relative slowdown, with growth rates lower than those of the general economy. In fact, the beginning of a divergence between MIS and consumption can be observed in the last quarter of the year.

Why is this happening? Someone could argue that one of the effects of the supposed positive impact of this measure should be the improvement in consumer confidence levels in the economy.

In the end, the dynamism that will occur, as the Executive argues, should lead to optimism.

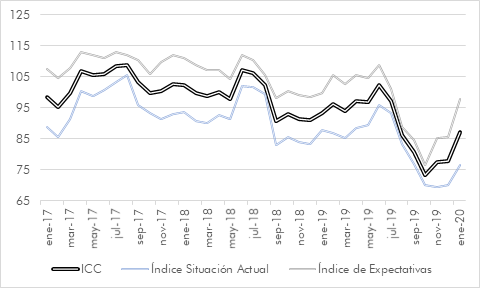

The Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) tells us that if consumers have a positive view of the current and future situation of the economy, their values are above 100 points, while the opposite is true.

Well, over the last year, especially in the second half, consumer confidence has plummeted to the lowest level since November 2013.

Certainly, it is still too early to establish correlations in the strictly scientific sense of the term, which does not prevent us from stating that the hypothetical capacity of the SMI to reactivate the economy has not been verified in the Spanish case in 2019, despite the significant rise.

Contrary to the theses advocated by the Executive, the labor market has experienced a slowdown in hiring and the economic projections for the following years continue to be corrected downwards.

It would not be honest to attribute the economic slowdown (only) to the increase in the MIS, nor to assert that it is a dynamic element of consumption and the economic cycle.

Wages are limited to collecting the marginal productivity of the worker. As long as the latter does not increase, the former will not be able to do so either without causing serious imbalances in the market.

There is no such thing as magic, not even if Pedro Sánchez decrees it.