Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic that is devastating lives and livelihoods around the world has also preyed on a more subtle victim: the conventional monetary and fiscal policies advanced by governments and central banks are longer sufficient in the face of the crisis. Economic proposals that seemed radical a week ago now seem timid. The most ambitious tax packages seen in years are now inadequate, just days after their announcement. In both Europe and the United States, there is an impression that institutions will need even more extraordinary policies to counter the paralysis of all economic activities.

Moreover, the coronavirus outbreak has exposed the fragility of a labor market characterised by a growing “gig economy,” zero-hour contracts, and self-employed workers. More specifically, in Spain, in March, up to 898,822 jobs were destroyed due to COVID-19, of which almost 70% correspond to temporary contracts [1], concentrated above all in the construction sectors, hospitality, and artistic or recreational activities. Adding to this number, 620,000 workers were affected by ERTE and 500,000 self-employed have requested the cessation of their activity. In the face of such a drastic collapse, the government’s measures still seem limited and show the need for more forceful policies.

Around the world, countries are also taking action, with billions of euros of items and extraordinary measures to help the most vulnerable companies and workers. Among the most innovative proposals is the reform proposed by the Trump Administration on “helicopter money;” that is, a direct transfer of money from the government to citizens to help them in this difficult time [2]. In fact, as Stanford University professor Jennifer Burns explains, “In a crisis situation where needs are likely to be widespread and very diverse, such as the coronavirus emergency, a cash payment seems more efficient in many levels. It can reach recipients faster, and they can use it right away to meet their most pressing needs, as determined by the best judgment of the individual and the household”[3]. In Spain, in recent weeks, the Sánchez government has outlined a similar proposal, under the name of «minimum vital income,» which, as will be analysed, is different from a universal income, and has completely opposite effects. However, in both cases (in the case of universal income and minimum income), the topic of dissension is its duration and, therefore, the total cost of its application.

The COVID-19 crisis is only highlighting more flaws in our economic structures. Among others, the growing precariousness of work, due to the emergence of the platform economy and decades of deterioration in the bargaining power of workers [4]. This issue is of concern to large investors in the finance sector, such as Jim Chanos, who believes that the coronavirus crisis will change social and political attitudes towards the most vulnerable employees, forcing companies to offer them more benefits [5].

Along with this evident instability of the labour market and the current social and health crisis, there is another risk that the worker will likely face in the near future: the automation of jobs and the need for new skills that cannot be easily acquired.

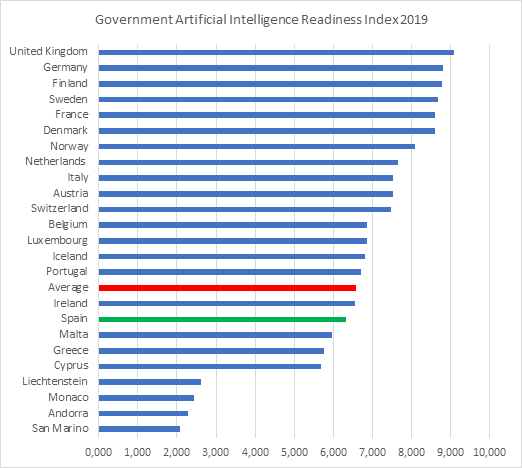

Labour automation and technological progress present both an advantage and a great challenge for countries. Companies can take advantage of new technologies like automation, to create new economic opportunities from new activities, improve the quality of traditional and emerging occupations, and increase the skills of their employees to reach their full potential and incorporate greater value added in jobs, some of which could never have been performed by humans [6]. According to a PwC study, these new technologies may contribute up to 14% to world GDP by 2030, equivalent to around 15 trillion dollars at current values [7]. However, the positive impact that this technological wave can bring to the economy will be absorbed in different ways depending on the countries, the industries, and the different jobs in the value chains. The Anglo-Saxon Institute Oxford Insights has recently released an index of governments’ readiness for artificial intelligence. The overall score is made up of 11 input metrics, grouped into four high-level groups: governance; infrastructure and data; skills and education; and public and government services. According to the institute, Spain is still below the Western European average [8].

Graph 1.

Furthermore, following PwC estimates, the Spanish sectors that would be most affected by automation would be manufacturing and construction, while education and social work would hardly change. On the other hand, forecasting the impact on employment is still not easy. Frey and Osborne (2013) have predicted that 47% of jobs in the US are at risk of automation. The OECD, using the same methodology and applying some criticisms made by other academics, has reached less worrying estimates, concluding that, in developed countries, this risk ranges from 7% to 12% [9]. The results still vary greatly and will depend on the ability of companies’ ability to monetise the investment they are making in artificial intelligence (AI). According to a survey by MIT and the Boston Consulting Group, carried out on more than 2,500 managers from 97 industries and 29 countries, 70% of companies currently have reported little impact of AI on their business. Furthermore, although investment in technology is increasing, companies do not always achieve a positive return [10]. Of course, despite the fact that the results are still not entirely reliable, the need for workers with specific knowledge of new technologies will be key to improving these advances.

In short, although the main data regarding technological evolution suggests that these changes lead to the destruction of jobs in the short term, followed by the creation of new and better ones, the technological advances of today emerge at an unprecedented pace, creating uncertainty about the future of the labour market. As reported by the International Labour Organization, in the European Union almost 50% of individuals between 15 and 24 years old believe that their current jobs could be carried out totally or partially by a robot or AI, compared to 40% of adults [eleven]. Therefore, despite the anticipation of a long-term increase in productivity thanks to technology, society feels the need for political action to defend itself against possible risks.

The Basic Universal Income

The dangers stemming from the fragility of the labour market (which have increased as a consequence of the COVID-19 crisis) have led many economists, politicians and intellectuals to propose a universal basic income (UBI), a request that has intensified in recent weeks.

Defined as «a periodic cash payment that is unconditionally delivered to all citizens individually, without the need for proof of means or work» [12], the UBI announces itself as a visionary solution to fight against inequality, poverty and job insecurity. First proposed in 1797 by Thomas Paine, it has been considered on different occasions throughout the 20th century, returning to debate in recent years as a result of the 2008 crisis (now, the health crisis) and the risk of automation in many jobs. Uncertainty about the labour market and the inefficiency of social security in many countries has motivated the discussion to open up to alternative forms. Furthermore, in recent decades, UBI advocates have desired to connect in an increasingly global network. The “Basic Income European Network,” created in 1986 to “serve as a link between all individuals and groups interested in basic income and foster informed discussion on this topic around the world,” [13] changed its name in 2004 to «Basic Income Earth Network,” due to the great participation of other continents.

Its drivers have been further increased after several experiments carried out in different countries. One of the most successful cases and most powerful through the media has been the Bolsa Familia Program (PBF) in Brazil, a program of conditional cash transfers with national coverage whose objective is to support families in extreme poverty, and expand access to education and health services. Unlike the UBI, the PBF is aimed at the most vulnerable families and depends on the fulfillment of various requirements, such as having “the updated vaccination card for children from 0 to 7 years old and guaranteeing a minimum attendance at school of 85% for children and adolescents from 6 to 15 years old, and 75% for adolescents between 16 and 17 years old ”[14]. The socioeconomic effects of PBF have been the subject of many academic studies. Since its initiation in 2003, available data shows that it has helped 36 million people live above the extreme poverty level [15]. Without going into the debate on the effects (positive or negative) that it has had on education and health [16] [17], it is necessary to begin from the basis that its structure and purpose deviate from those of a possible universal income basic in the most developed countries. The differences lie not only in the unconditionality of the UBI, but also in its possible impact on society and on the labour market, which is completely different in Brazil than in European countries such as Spain or Italy. These structural divergences mean that studies of developing countries do not necessarily justify the application of this reform in the rest of the world.

However, Western countries are also serving as a testing ground for the proposal and are attempting to reach conclusions. In fact, in the last century, there have been many cases of experimentation in more developed nations. Unfortunately, here too the limits are clear and, although they may offer interesting results, they are not very useful, apart from keeping the discussion alive.

An example that most likely reflects the UBI is the income distributed in Alaska to all residents as an annual dividend from the profits of the country’s natural resources [18]. However, although the income is universal and unconditional, by itself it is not enough for the citizens to subsist. As reported by the institution in charge of the program, the annual dividend distributed in 2018 per individual amounted to $1,600 [19]. Therefore, such a policy would have no effect on the labour market or on people’s lifestyles.

Furthermore, in 2017, another experiment on universal income (the most recent in OECD countries) was carried out in Finland with the aim of analysing certain social and labour behaviors. It resulted in comparing various effects on two groups of unemployed citizens. The project consisted of delivering a basic income of 560 euros per month, tax free, for 24 months to 2,000 unemployed people between 25 and 58 years old, who were randomly chosen from 175,000 people across the country that received some type of subsidy for unemployment. Those selected continued to receive basic income even if they found work during this time [20]. The experiment had no effect on the participants’ employment status during the first year. However, at the end of the year, the recipients of the basic income found that their well-being had improved compared to the individuals in the control group (i.e. the rest of the unemployed who had not received the aid). However, as can be read in the official document of the Finnish government, «the results are somewhat preliminary, and it is not yet possible to draw firm conclusions regarding the effects of the basic income experiment» [21]. Similar and even worse conclusions were obtained in the Netherlands, where a group of researchers simulated the introduction of a universal monthly income of 700 euros for all citizens between 18 and 64 years old, based on the country’s minimum wage [22]. According to one of the researchers, Ive Marx, a basic universal income «would be enormously inefficient if it cared about the less wealthy in society» [23].

In the United Kingdom, in recent years, both the Green [24] and Labour [25] parties have increased their interest in this economic measure and have proposed to study it in greater depth. In France, several socialist presidential candidates outlined various variants of a basic income. The most radical reform proposed replacement of social assistance and benefits at work with a basic income set at a level slightly higher than the amount of social assistance for a single person. In a similar vein, other politicians, intellectuals and academics in Europe and in the United States believe that the digital revolution we are experiencing is unique and that it cannot be assumed that workers with the highest risk of automation have the necessary skills to continue to be competitive in the future. In the United States, Andrew Yang, an American businessman of Chinese origin and candidate for the 2020 primaries of the Democratic Party, has outlined a universal basic income of $1,000 a month for every American over 18 years old in response to the substitution of humans for robots in jobs across multiple industries. Elon Musk [26] and Mark Zuckerberg, founders of Tesla and Facebook, respectively, are just two of the multinational tech entrepreneurs who promote the possibility of doing more research on a universal income. According to both CEOs, in the near future, similar policies must be promoted to defend the weakest against technological changes.

However, a lasting problem of the UBI its unpredictable effects on the labour market and on the social norms of a country. In fact, there are four main limitations that make the experiments carried out to date not be extrapolated to reality. First, they are held for a limited time. Since participants can anticipate this fact, their behavior is likely to differ significantly in real life from that displayed in these observational studies. Second, participation is often not mandatory and therefore self-selection bias cannot be entirely ruled out. This decreases the relevance of the identified effects. Third, most of these trials analyse a small part of the labour market. It would be completely different if they were applied throughout the country [27]. The fourth structural problem is that the experiments carried out to date have almost always been financed by private institutions that are interested in them. In a real case, the costs would be met, at least in part, through taxes, and therefore the end effect would not be the same for all citizens.

However, despite these problems that exist by definition in the universal income experiments and that make their conclusions incomplete, there have been different criticisms that the UBI faces in its possible implementation. On the following pages, the main ones will be presented, while offering the responses of their defenders [28].

Disincentive to work

The first criticism against universal income focuses on its impact on the labour market. Many believe that giving a basic income to all citizens without any conditions can create a disincentive to work, since many would prefer to leave their jobs and enjoy other unpaid activities. This would lead to an increase in unemployment and, therefore, a decrease in the economic growth of a country. In addition, separating remuneration from physical activity could not only generate unemployment, but also promote idleness. As mentioned above, the experiments carried out so far cannot be considered valid when determining the effects on the labour market. The duration limit for most of them does not create a real incentive for people to quit their jobs. If the basic income is subject to a study, the participating individuals know that, once this is finished, the basic income will disappear and they will have to go back to looking for a stable job. Not to mention, the existing analyses do not usually contemplate the distorting effects of the greater progression and fiscal pressure necessary to publicly finance basic income.

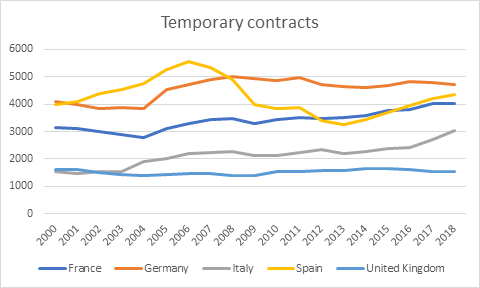

On the other hand, its advocates criticise, first of all, the inefficiency of unemployment benefits in force in many Western countries, which leads to the unemployment trap. They affirm that both the tax rate and the welfare system can jointly contribute to keeping people unemployed and, therefore, collecting social security, because the reduction of state aid once a person beings receiving income from poorly paid work means no significant increase in total income. Therefore, the individual considers that the opportunity cost of returning to the labour market is too high, as there is too little financial return, and this can create a perverse incentive not to work. This trap is overcome in the case of a universal income: money does not depend on the employment situation of people, who can continue to receive it regardless of whether they have a job or not. Likewise, it would help to find a more stable situation for the most vulnerable social strata, such as those subject to precarious contracts, which has clearly increased in the last 20 years. Rapidly changing labour markets are blurred lines between traditional employment and different forms of self-employment.

Graph 2.

New types of employment also make it more difficult to reliably assess whether or not someone is working, and thus link social protection rights and contributions to people’s employment status. Therefore, if the existing targeting strategies do not provide adequate coverage for all those who need it, moving towards greater universality constitutes an option to keep social protection accessible [29]. For this reason, universal income presents an alternative that would give much more freedom when choosing a job.

The fact that it is universal and does not present any obligation (apart from being a citizen of the country in the program) allows them to have greater negotiating power in order to accept a job, and also the freedom to deepen their own training or to invest in new business. Even so, it is the production within a company and, therefore, the work of the people, that would mainly finance this reform.

That being said, it is clear that such a radical change in the labour market cannot be isolated from other fundamental aspects of our society. Workers are not purely rational subjects who follow precisely the laws of economic theory, and indeed the social and behavioral consequences of people cannot be easily described without citing other variables such as work ethic and justice with other citizens. Similarly, a reform of the labour market would affect all the mechanisms of the welfare state, even questioning its own efficiency.

Total cost

However, the great challenge for a universal basic income is in its general fiscal cost and in the amount of taxes that all those above the threshold would have to pay. In order to analyse it, we assumed that the Government of Spain decided to carry out this economic policy to face the COVID-19 crisis in the medium term, and in the long term, to mitigate the risk of automation and job instability. Before continuing on to expose the most efficient ways to pay a basic universal income, it is worth calculating how much your total amount would amount to.

According to the latest data published by the INE, corresponding to July 2019 [30], in Spain there are 38 million inhabitants over the age of 18, who, as citizens, would be eligible to receive a basic income. As previously stated, this aims to give each person the possibility of having a decent life without the obligatory need to work. Based on the fact that the minimum wage may be a valid standard, in our country, this income should be estimated at approximately 1,000 euros per month per person, which would mean a total cost of 456,000 million euros per year, the equivalent of almost 30% of GDP. A measure of this magnitude cannot count on significant cuts in public spending and should be financed through taxes.

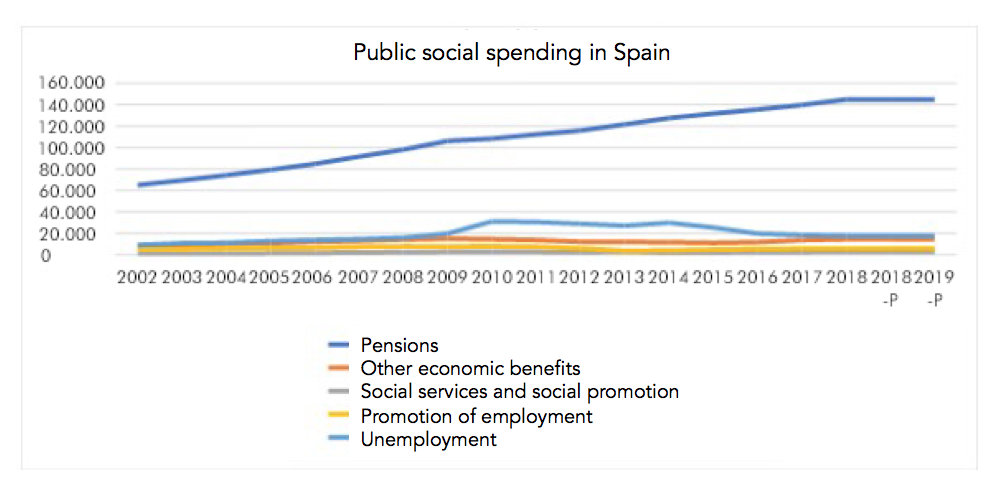

With regard to this point, according to economists and promoters of basic income Philippe Van Parijs and Yannick Vanderborght, the best way to pay it, at least in the most developed countries, would be articulated, on the one hand, through the tax on income, and on the other, substituting social assistance expenses. Transferring this theory to the specific case of Spain, the following can be concluded: the items of public spending related to social policies that could be replaced to finance a universal income would be pensions, employment promotion and unemployment benefits, services and promotions. social, and finally, other economic benefits. As can be seen in the following graph, this would give a total of 185,268 million euros budgeted for 2018. After a cut of these dimensions, there would still be 270,732 million to cover, which would have to be paid via personal income tax and other taxes. However, in 2018, Spanish tax income from personal income tax, VAT, Corporation Tax and Special Taxes reached 208,685 million euros. There is no doubt, therefore, that a policy of this proportion would require a huge tax increase and an incredible cut in public spending.

Graph 3.

Minimum Life Income

Instead, the Government of Spain, in recent weeks, is designing a Minimum Vital Income (MVI) that, although it may seem like a universal income, exhibits an essential difference: in the short term, the MVI is designed to help people hardest hit by the COVID-19 crises and who have not received help through any other measure [31] and then, in the long run, support only the neediest families. Furthermore, while basic universal income is applied at the individual level, the reform proposed by the Government would correspond to households; millions of them, by the calculations. On the other hand, as Minister José Luis Escrivá has stated, this measure is designed to have a “permanent character.” Regarding the amount, exact numbers have not yet revealed. However, using the electoral program of Podemos in 2019 as a reference, it would likely be «from 600 euros per month, which would increase depending on the number of household members up to 1,200 euros» [32]. This would represent an annual cost [33] of between 7,000 million and 14,400 million euros, financed mainly, according to Escrivá, with debt issuance and with savings of around 2,000 million euros that would be achieved over time through of the absorption of other non-contributory state aid [34].

The problems related to this measure are several and add to the limits of a universal income. First, the MVI would lose its hypothetical positive effect in destroying the poverty trap. In fact, although it is not clear how long the minimum income would remain in force after the recipients found work, its fundamental objective is to help the most vulnerable. Therefore, this would, in any case, make a person who received a minimum vital income wonder whether to continue receiving the aid or earn more money for their work. This line would end up becoming the main problem of the MVI, complicating its administrative simplicity when it comes to distinguishing who should become its recipients and who should not. Furthermore, as mentioned throughout this article, no experiment carried out to date has been able to show a positive effect on the labour market.

To this must be added the costs of financing this measure. Discounting the 2,000 million that were saved from other subsidies, the Government would need to continue paying between 5,000 and 12,400 million euros. According to the latest IMF estimates, Spanish debt will increase to 113% of GDP after the coronavirus crisis. Although this measure would be cheaper than a universal income, in the coming years, the Spanish Executive will need to be more careful in its public budgets, which will already have to be increased due to health expenses and business aid. Another method of financing the MVI under consideration would be the consumption tax, that is, the VAT. This tax, which already reaches 21% of the final price of most products, would deal one more blow to consumption. According to a survey carried out by the American consulting firm McKinsey, Spanish consumers are among the least optimistic in Europe about the economy, and already feel an impact on their income, planning to cut their spending in almost all sectors [35]. Finally, implementing a permanent measure limited only to a group of individuals would create an even more perverse and state-dependent system, until the benefits of a basic universal income are lost.

Conclusion

Thus, a basic income for all citizens would lead to greater administrative simplicity and would provide a degree of security in a rapidly changing labour market. A universal income would also provide people with greater flexibility to manage work, family and other personal interests. It would also avoid the social and economic costs of the unemployment trap, or other conditions of receiving social benefits.

However, major concerns exist surrounding unintended consequences. Furthermore, this transfer would require very substantial additional tax revenue and would reduce people’s benefits. At a time when many countries are experiencing a terrible health crisis, none of them can afford to cut social spending. Although a basic income may help the most affected groups to survive in the short term, in the long run it is not sustainable. What is really needed is a greater and more efficient investment in healthcare and in the defence of an increasingly mobile labour market.

Regarding the risk of automation of work and a more technological and difficult to manage society, these are two great challenges that all countries will have to face. On the one hand, we must help workers whose jobs pose the greatest danger of automation to learn new talents. On the other hand, it is true that it is not always feasible to change your own skills and, therefore, society must promote innovations increasing opportunities for ordinary employees, and not only for those that end up replacing them. As MIT professor Daren Acemoglu reports, “The future of good jobs depends largely on our ability to take advantage of new technology platforms such as AI to create meaningful and well-paying jobs for humans, rather than just seeking to replace workers in each link of the production process ”[36].

Finally, if the MVI is approved, it should be articulated with a financing system that provides future stability and sustainability, taking into account the possible perverse effects that underlie it. There is no point in generating a greater volume of aggregate public spending if this leads to a higher level of debt and a new deficit public aid system. Failure to do so with the required rigor would further aggravate the Spanish economy.

[1] Datos publicados por el Ministerio del Trabajo.

[2] White House warms to showering US with ‘helicopter money’. Financial Times (18 marzo 2020).

[3] Stanford University, news. 20 marzo 2020.

[4] Capitalism’s Triple Crisis. Mariana Mazzucato. Project Syndacte (30 marzo 2020).

[5] Moral Money. Financial Times (3 abril 2020).

[6] Future of Jobs Survey 2018. World Economic Forum.

[7] How will automation impact jobs? Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2018.

[8] Government Artificial Intelligence Readiness Index 2019. Oxford Insights.

[9] The risk of automation for Jobs in the OECD countries. OECD, 2016.

[10] Winning with AI. MIT Sloan Management Review and Boston Consulting Group, 2019.

[11] Global Employment Trend for Youth 2020. ILO

[12] https://basicincome.org/basic-income/

[13] BIEN: https://basicincome.org/about-bien/

[15] ILO

[16] Soares, F., Ribas, R., & Osório, R. (2010). EVALUATING THE IMPACT OF BRAZIL’S BOLSA FAMÍLIA: Cash Transfer Programs in Comparative Perspective. Latin American Research Review, 45(2), 173-190. Retrieved January 23, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/27919200

[17] Shei, A., Costa, F., Reis, M. G., & Ko, A. I. (2014). The impact of Brazil’s Bolsa Família conditional cash transfer program on children’s health care utilization and health outcomes. BMC international health and human rights, 14, 10. doi:10.1186/1472-698X-14-10

[18] Alaska Permanent Fund: https://apfc.org/

[19] Permanent Fund Dividend Division: https://pfd.alaska.gov/Division-Info/Summary-of-Applications-and-Payments

[20] The basic income experiment 2017–2018 in Finland

[21] The basic income experiment 2017–2018 in Finland Preliminary results

[22] Basic income doesn’t work, Antwerp research suggests. Flanders Today (18 abril 2018).

[23] Twitter: https://twitter.com/IveMarx/status/1033038589838479361 (Traducción del autor).

[24] Green Party Manifesto 2019: https://www.greenparty.org.uk/assets/files/Elections/Green%20Party%20Manifesto%202019.pdf

[26] https://www.businessinsider.com/elon-musk-universal-basic-income-2016-11?IR=T

[27] Basic Income. P. Van Parijs and Y. Vanderborght, 2017.

[28] Otra crítica clásica en contra de la renta universal básica es el riesgo de inflación. Sin embargo, una renta universal no tiene por qué ser consecuencia de imprimir más dinero por parte del gobierno.

[29] OECD (2017), “Basic income as a policy option: Can it add up?”, Policy brief on the future of work, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[30] Instituto Nacional Español: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=9663&L=0

[31] Hay que señalar sobre este punto que el grupo más beneficiado sería, probablemente, la economía sumergida.

[32] Programa de Podemos. 2019. https://podemos.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Podemos_programa_generales_10N.pdf

[33] El coste total dependerá del número de destinatarios y la cuantía por persona. Según las estimaciones de Airef del 2019, el coste total podría ser, como mínimo, de 5.500 millones de euros.

[34] Los Programas de Renta Mínima en España. Airef. 2019

[35] Global surveys of consumer sentiment during the coronavirus crisis. McKinsey, abril 2020.

[36] It’s Good Jobs, Stupid. Daren Acemoglu, junio 2019.